Cameron’s second refugee U-turn: Still too little, too late

You might be forgiven for believing that the refugee crises across the Middle East and North Africa and the tragic dramas on the coasts of southern European states started only on 2 September 2015. The distressing image of three-year-old Aylan Kurdi’s body washed up on the shores of Turkey has clearly touched millions.

Many may ask why the thousands of other lifeless corpses across Syria and Iraq did not have the same impact. Those killed by chemical weapons in Syria were as helpless and as innocent. It highlights if nothing else the effect of a powerful image in the eternally connected world we live in to break though the oceans of information, news and even horror.

Aylan Kurdi’s legacy may be similar to that of Muhammad Bouazizi, Khaled Said, Muhammad al-Durra and Hamza al-Khatib. The key difference is that the deaths of these people triggered mass protests in the Middle East whereas Aylan’s image stalks European consciences.

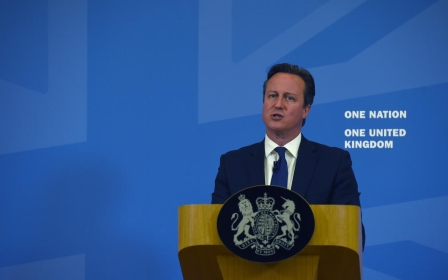

The sudden surge of public sympathy clearly caught many European politicians off guard and none more so than David Cameron, the British prime minister. An anti-migrant position had seemed to serve him well. His recent comments about “swarms” of migrants barely damaged him in the polls or amongst his core supporters to the right of British politics. This might explain why he was so slow to react to this major change in public mood. Local councils started offering to take in refugees.

Nicola Sturgeon, the Scottish first minister, announced that Scotland would accept 1,000 more. Celebrities such as Bob Geldof publicly announced that they would open their homes. Charities reported a huge spike in donations to help refugees.

So on 4 September, David Cameron shifted. The plans are as yet unpublished. Parliament returns next week, so civil servants will be sweating over the weekend with the fine detail for ministerial approval. The prime minister declared that the UK would accept “thousands” more.

This was his second U-turn on Syrian refugees following the belated announcement that Britain would set up its own Syrian vulnerable persons relocation scheme on 29 January 2014. All the same arguments were trotted out then, too, as to why not to do it. Eventually the government relented and the result 20 months later is that Britain has taken in a miserly 216 Syrians under the scheme. This is in addition to 5,000 Syrians who have successfully sought asylum in the UK.

What made Cameron change his position? He acknowledged that “Britain has a moral responsibility to help refugees”. Yet this existed pre-2 September, so why the change now? Public pressure was certainly significant, but there were also other concerns. Cameron is engaged in a delicate renegotiation of Britain’s place in the EU with many states who are angered by Britain’s position on refugees. There was a danger of this affecting Britain’s image internationally, especially in many friendly Arab states.

The British government does have a record to defend on Syrian refugees. After all, it has donated over £1 billion to the Syria crisis, far more than any other EU state, making it the second largest bilateral donor globally. According to Oxfam’s latest report in March, whilst Britain had contributed 110 percent of its fair share to Syria, France and Italy had only committed 11 percent and Germany 38 percent.

It remains the UK government’s position that assisting the refugees in the region is better value for money than bringing them to the UK. Nevertheless, aid agencies rightly call for a hybrid approach that includes development aid in the region but also a generous resettlement policy for the most vulnerable. It should not be an either-or approach. Major agencies called last year for Britain to settle 10,000 Syrians, including those currently in Europe. It is doubtful that government plans will hit that target.

This is why the region cries double standards. Jordan and Lebanon in particular are overwhelmed by Syrian refugees, as well as historic Palestinian refugee communities. The British position assumes that these small states can just continue to house more and more. Lebanon, with a population of 4.5 million, has 1.5 million Syrian refugees. If Britain took an equivalent share, it would be hosting 20-25 million refugees.

But then again, many correctly ask what role the rich Gulf States are playing in helping the refugees? How many Syrians have been granted asylum in Saudi Arabia for example? The UK may have resettled only 216 - but this is 216 more than all six Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states. These oil-rich states have yet to resettle a single refugee.

Britain also has a more direct responsibility. It was a leading actor in the decision to intervene in Libya. The chaos and upheaval in the North African state that followed was in part a result of the lack of attention given to it after military action ceased. In Syria, Britain and its allies have lamentably failed to push for a political solution, the only way in which the refugee flows will be stemmed. And the UK is one of the leading arms exporters to the Middle East including to many states that have been arming parties to the Syrian and Libyan conflicts.

The refugee issue forms a nightmarish perfect storm for David Cameron as it lies at the crux of three of the most challenging policy areas for his government – Europe, immigration and the Middle East. Domestically and to keep his party together, Cameron needs to be tough on Europe and avoid any new European refugee quote schemes but at the same time he has to reach out to European partners. This is why he cannot accept refugees from Calais but will only consider those currently in the refugee camps in the Middle East. He does not want to undermine EU asylum regulations, nor as government ministers argue, fuel the people-smuggling industry.

Greece, Hungary and Italy, the EU states bearing the brunt of the refugee surge, will not be impressed. He has to be tough on immigration but find a way to package a deal for refugees. And he desperately needs a Middle East policy that has a chance of working if for no other reason than to stem the flow of those fleeing conflict.

Even Cameron’s plan to extend bombing the Islamic State (IS) group in Iraq to include Syria (hardly a winning strategy) will probably fail to get parliamentary support, if the anti-war politician Jeremy Corbyn wins the Labour party leadership this coming week.

This round of the argument may have resulted in a small but significant victory for those who want to see Britain maintaining its historic record as a place of refuge. The debate however, is far from over. The far right and anti-immigration lobby will be far from cowed. Some local councils may not be overly willing to play hosts and will demand central government foot the bill.

Overall Cameron will still be hurt by the charge that this is too little, too late. His government has appeared grudging, not welcoming. He is following public opinion, not leading it.

But one argument has perhaps been settled. For most of the last four years, a large segment of British, and indeed European, society has argued that events in the Middle East are not our problem. They are being a bit quieter now. Just perhaps the threat of an ever-expanding refugee crisis will be the proverbial kick up the backside to European politicians to get serious about solving conflicts on their borders rather than ignoring them or even stoking them. That would be a truly fitting legacy to Aylan Kurdi and his family.

- Chris Doyle is the director of Council for Arab-British Understanding. As the lead spokesperson for CAABU and as an expert on the region, he is a frequent commentator on TV and radio and gives numerous talks around the country on issues such as the Arab Spring, Libya, Syria, Palestine, Iraq, Islamophobia and the Arabs in Britain.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: File photo shows British Prime Minister David Cameron (AFP)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].