Is the trauma of Paris blinding us over the reality of Syria?

“War took his home, don’t let winter take his life” reads a charity advert for Syrian children plastered onto the side of a tube carriage on the London underground, on behalf of the Department for International Development, the aid branch of the UK government.

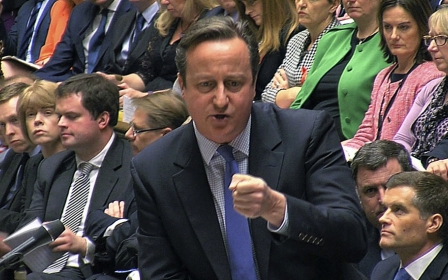

The spectacle of a Christmas charity appeal posted by a government - to help people of a country that that very government is now bombing - is not only horribly ironic, but makes use of emotive rhetoric which masks a stark reality. It seems that a similar strategy has been harnessed by British Prime Minister David Cameron in the emotional wake of the Paris attacks; a strategy which was perhaps instrumental in swaying the UK government to decide to bomb Syria.

A small sample of Cameron’s opening speech to the House of Commons during the 10-hour debate on Wednesday, reveals the extent of the emotional scarring of Paris and echoes of a similar rhetoric that launched the disastrous War on Terror after the 9/11 attacks in the US.

For example, Cameron spoke of the “fundamental threat” of the “women-raping, Muslim-murdering, medieval monsters” of an “evil death cult”. He continued, and spoke of those who are “plotting to kill us and to radicalise our children” whilst bringing “terror to our streets”, with their “poisonous extremist ideology” and “warped ends”.

The word “evil” that peppers Cameron’s speech connotes an all-encompassing immorality and wickedness. It is an adjective more closely suited to fairytales than legally-based terminology, which would perhaps be more appropriate for a discussion on whether to engage in an international military offensive.

“Evil” suggests ISIL are a dark spectre who were not made, but independently crawled fully formed out of the shadows, rather than a political terrorist faction with an origin, evolution and agenda.

To paraphrase Dylan Thomas, no one is wholly bad or wholly good, and by reducing the debate to simplistic binaries of a moral crusade pitched against inherent forces "evil", Cameron is not acknowledging where ISIL came from, nor what provides the basis of their political support. This is integral to any understanding of how a long-term solution for the instability of the region is to be found.

This is not to say these descriptions or the use of the word “evil” is necessarily false, nor does it dispute that ISIL are capable of causing brutal and inhumane acts which severely violate fundamental legal and moral codes.

What happened in Paris was unforgivable and indefensible, but that does not mean that bombing Syria is a justified retaliation, or that there should be a time and a place for such semantics.

Sensationalist language should not masquerade as logical debate in parliamentary procedure, just as emotional sentiment should not form the basis of the decision of whether to send British forces to war. One of Jeremy Corbyn’s first steps as the leader of the opposition was to try and eliminate the theatrics of Parliament, and now more than ever we need hard reason, cool-headed logic and a diplomatic strategy, not a rushed and heated battle cry.

It seems that Cameron is perhaps confusing a clear-minded legal intervention with hot-headed punishment – which begs the question, if Paris had not happened a few weeks ago, would Britain be bombing Syria today?

Whilst it would be anachronistic to rely too heavily on historic examples, there are obvious parallels to terrorist attacks such as 9/11 sparking international intervention without a proper political strategy in place, where politicians perhaps react too much with hearts rather than minds, emotion rather than reason.

A lack of strategy

One of the indicators that Britain’s move to bomb Syria is perhaps a rushed reaction to Paris is the lack of a strategic justification for the decision.

Long gone are the days when Britain was a leading military power; Britain’s army has shrunk 20 percent since Cameron stepped into office and is the smallest it has been since the 1800s. As argued by Matthew Weaver and Julian Borger in The Guardian, Britain’s precision-guided Brimstone missile is not all that valuable in minimising civilian casualties when it is not acting on accurate intelligence. On 1 May, for example, US-led airstrikes in Aleppo led to the deaths of over 60 civilians, seven of whom were children, due to allegedly misguided information over the location of ISIL members.

Like many other commentators, former Republican presidential nominee John McCain acknowledged on Wednesday that there is little strategic rationale behind Britain joining the airstrikes; it is merely a symbolic gesture.

“We will have some token aircraft over there from the British and they’ll drop a few bombs, and we’ll say thank you very much. The president will be able to say ‘now we have the British who will be helping us’, and that’s good,” he said.

“It’s good to have shows of support from our British friends,” McCain added, “but to say that it’s going to make a significant difference, no, I’ve got to be a little more candid than that.”

Glen Greenwald, the founding editor of The Intercept, told Middle East Eye that the purpose of the expanded airstrikes is to make Britain out to be “some sort of powerful, relevant, military actor…It’s all about the pose and self-image, showing Britain as [standing] up – from a nice safe distance of 30,000 feet in the air - to whoever is the newest Muslim villain group.”

The US, on the other hand, has twice the defence budget of all the NATO members combined. Before Britain joined the strikes on Thursday morning, US-led “Operation Inherent Resolve” has been bombing both sides of the Iraq-Syria border for almost 17 months now, undertaking approximately 3,000 airstrikes in Syria.

Thus it seems the vote in the House of Commons reveals more about Britain's concerns over self-image after an incident such as the Paris attacks, rather than a political solution to a disastrous four-year conflict.

A futile war?

As Jeremy Corbyn essentially underlined, the Prime Minister is “entirely unable to explain how UK bombing in Syria would contribute to a comprehensive negotiated political settlement of the Syrian war”.

It is true, US-led airstrikes have helped stop ISIL capturing tactically advantageous areas in the region, such as the Kurdish stronghold of Irbil and Kobane on the Turkish border. But whilst the age-old tactics of divide-and-conquer are based on short-term military success, the problem really lies in the aftermath of such "victory".

ISIL is only one aspect of Islamic extremism which feeds from destructive Western interventions in the Middle East, and bombing Syria seems to be merely adding fuel to ISIL’s recruitment appeal.

Cut off the head of the hydra and seven more will spring up. Or, to use another analogy borrowed from Guardian columnist George Monbiot’s tweet on Thursday, we have “stepped into the lobster pot...Easy to get in, hard to get out”.

Historical precedent with Libya and Iraq indicates we are trapped in a vicious cycle, and this will merely evolve into another failed bombing campaign in the Middle East, which will in turn further fertilise the ground for extremism.

Perhaps in this time of confusion, and especially regarding the horror which unfolded in Paris, we should look to history to help instruct the present. As the idiom goes, insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.

- Megan Hanna is an independent freelance journalist and photographer, based in the occupied Palestinian territories. You can follow Megan on twitter via @Megan_Hanna_

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

AFP: A photo taken on 6 December, 2015 shows a French flag with a drawing placed at the foot of the central monument on the Place de la Republique in Paris in memory of the victims of the November 13 attacks (AFP).

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].