On IS front line, Iraqi Christians left to care for abandoned synagogue

AL-QOSH, Iraq – A narrow doorway opens up into a courtyard. The path to the wooden door of the synagogue is overgrown with weeds and shrubs; its walls are crumbling and, in parts, completely fallen down.

A red tin-roof and metal scaffolding hold the eroding structure in place. A barbed-wire fence covers holes in the walls to keep children and stray animals out, although it is easily passable for an adult.

“My father and my grandfather grew up with the Jewish people in this area,” Sami Nasir tells Middle East Eye.

Nestled between densely built Iraqi homes and the ancient Assyrian churches of al-Qosh, the 800-year-old synagogue, believed to be the burial place of the biblical prophet Nahum, lies in near-ruin.

Although the Jewish residents of al-Qosh are long gone, many having fled after the creation of the state of Israel in 1948, Nasir and his extended family have taken over the upkeep of the abandoned synagogue. They open the locked doors, sweep the floors and remove rubbish brought in from the wind or left by passing visitors without regard. Nasir took over this responsibility from his father and takes it very seriously.

When Nasir’s father passed away, he told him, "No matter how much God gives you in life, you must take care of this place."

Nasir is an Assyrian Christian, as are the vast majority of the residents of al-Qosh. The town is located in the Nineveh plains, which has deep roots in Christian heritage, most notably the Chaldean Monastery, which is carved deep into the steep cliffs off the mountain just north of the village.

Since the appearance of the Islamic State (IS) in Iraq, many Christian villages across the Niveveh plains have fallen under control of the militants.

The largest such village is Qaraqosh, 30km south-west of Mosul - which is still under the control of IS. In August 2015, residents of Qaraqosh and other Christian villages fled to safer parts of Kurdistan as IS put their villages under siege, adding another 100,000 displaced people to Kurdistan’s growing humanitarian crisis.

Fighting has not yet reached the village of al-Qosh, but Tel Skuf village, a mere 17km away (approximately a 20-minute car journey) was besieged, then recaptured from IS, and is still a location of fierce fighting between IS militants, Peshmerga forces and Christian factions who have emerged.

The synagogue seems largely forgotten. “Just a few people ... come here. Sometimes foreigners come. There have been visitors from Holland, Denmark, and Germany,” Nasir tells Middle East Eye. “They believe in the culture, the Prophet, the Old Testament.”

“This is a very historical place and if we do not take care of it, it will be destroyed, and will be gone. In maybe just 10 years, this place will be destroyed,” Nasir tells MEE.

This is a matter of great concern to Nasir, who repeatedly mentions his great love for the holy site. “I really love it,” repeats Nasir.

But now with the frontlines between Kurdish forces and IS militants only a short car drive away, Nasir is concerned for the safety of his four young children - Jessica, Sami, Antony, and Sarah - and expresses the all too common desire to move abroad, a move which would leave the fate of the fallen synagogue in limbo.

“My brother will take care of it next because he will never leave this country,” says Nasir. “I don’t need to leave myself, but for the children I need to leave. Maybe I will come back one day.”

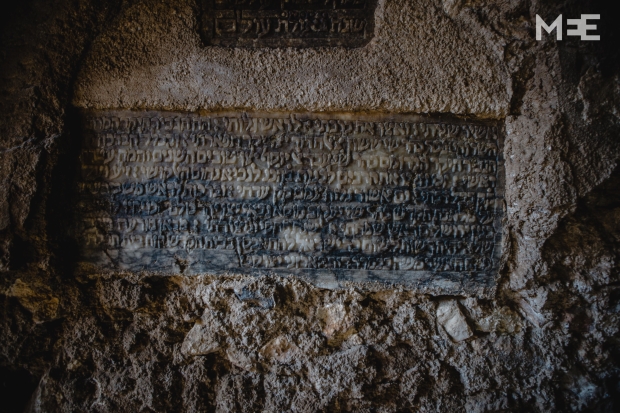

With his two children by his side, one holstered up on his hip, the other wrapped around his leg, Nasir lights a candle in an enclave chiselled into the interior walls of the synagogue. A few foreign Christian visitors have been to the synagogue today and a few candles already burn. Hebrew inscriptions engraved into the wall are visible next to him.

“I am proud to take care of this place,” Nasir says with a smile and a sigh, but who knows what will happen to it once he is gone.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].