Even Harry Potter can't break the siege on Gaza

Sixteen-year-old Abdullah Hamdan is familiar with the name Harry Potter. He's heard all about the famous fictional wizard. The media buzz that has surrounded the character for over a decade now has not eluded him. But he’s never been able to get a copy of any of the books or even see the globally renowned series of movies in a cinema like other fans around the world.

The information he gets about the world famous franchise is purely through social media reports emanating from outside of his blockaded homeland of Gaza. Hamdan wishes he could have enjoyed the excitement of the Potter phenomenon at its height along with everyone else.

Even now, he still just wants that little bit of escapism to take him away from the harsh reality of the tense situations surrounding him and escape, as millions of other youngsters have, into the world of magic and fantasy by immersing himself in the world of Hogwarts.

“I have Facebook friends who live around the world. I can communicate with them but yet I can't get my hands on a simple children's book,” he says.

This teenager’s intellectual capacity, education and literacy levels are higher than average, but he feels his wider social mobility and human interaction is frustratingly stifled and he feels “too far away from the rest of the world”.

He knows that his quality of life and freedom of choice would be better if he lived just slightly over the separation fences surrounding Gaza - in nearby Sderot of Israel, or Egypt’s El-Arish - where global mail flows freely and no one is stopped from communicating with the outside world.

"My cousin ordered a book for me from Italy once, and online tracking showed it was delivered, but, sadly, I never received it. I was so disappointed,” he says.

Gaza’s incoming and outgoing mail services have been dysfunctional for a long time, so lost deliveries are not new to Hamdan. He is aware that many of his friends have no access to decent libraries and only access certain texts online - if there is electricity and no prolonged power cuts to shut Gaza out from the rest of the world.

“I have a dream of owning a Kindle, to connect online, store my favourite books, and explore the world. He who who does not read misses so much knowledge, self-empowerment, pleasant contemplation, reflection and inner peace,” he says.

He knows that when the electricity supply is on, he can access reading materials online, but nothing matches the feel of a real book in your hands and turning the pages with your fingers to the next part of the book.

“What we want [is] to feel the books in our hands and sink into the story.”

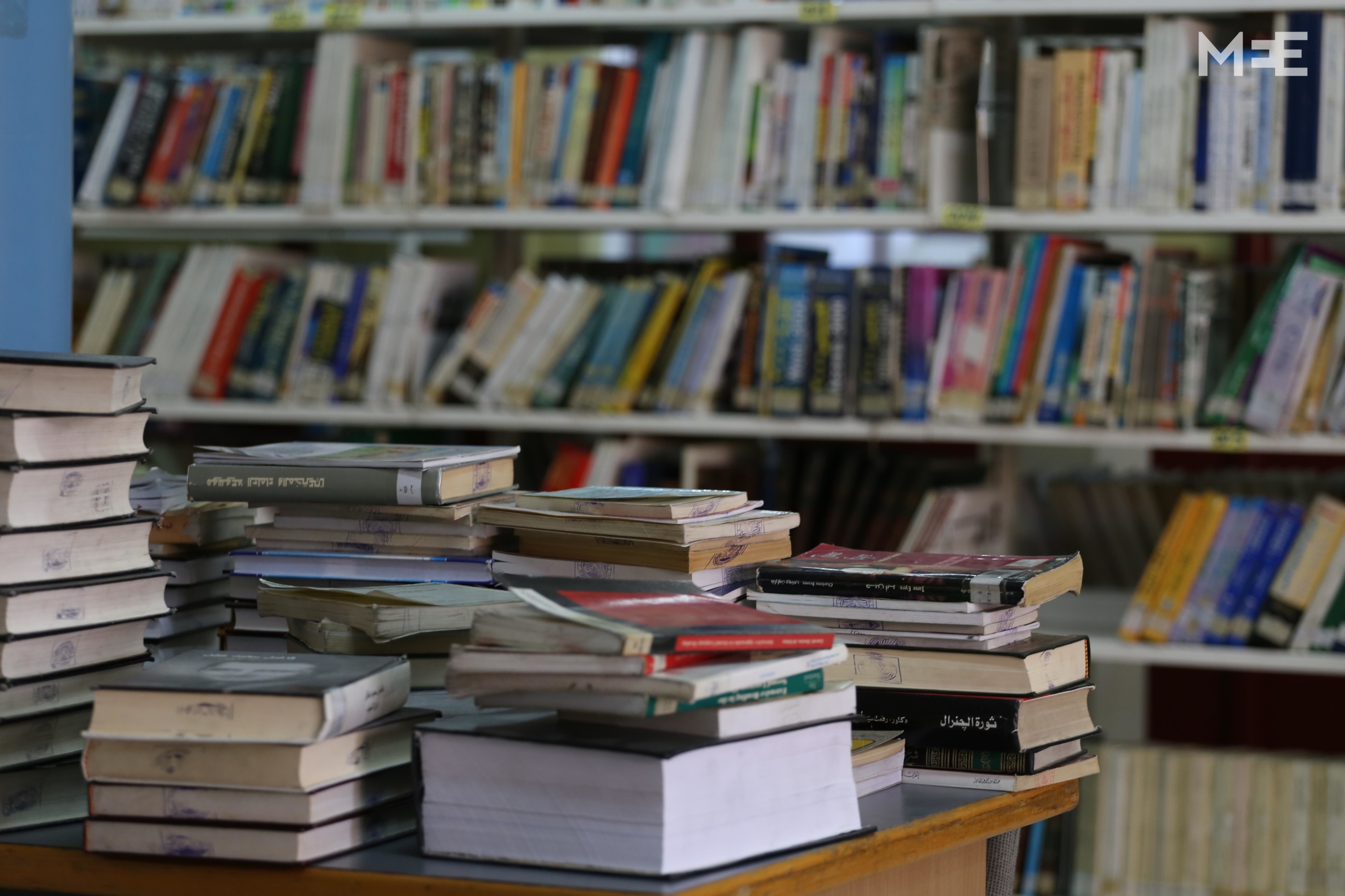

When Hamdan visits the public library in Gaza City, he is disappointed to see the limited supply of the same old books. “There is nothing new; it feels as if the flow of knowledge is jammed. I know it's not this way elsewhere, but in this library, and in blockaded Gaza more generally, I feel it more,” he says.

The ongoing blockade has forced Gaza to survive, since 2006, essentially on what books they have, until other supplies arrive, sporadically. It seems nonsensical to many that books would be blocked or banned from entry into Gaza by Israel, but that's just another part of the inhumane siege. It is not only books, but the UN says that Gaza will be uninhabitable by 2020, a prediction that makes talk about books seem less relevant.

Books for UN-run and government schools are often allowed through to Gaza from the West Bank, but not other books outside the curriculum. In 2009, UNRWA succeeded in convincing Israel to allow at least some books and school materials into Gaza.

Out of order

One Palestinian chief negotiator authored a book entitled Life is Negotiations, but Hassan Abu Attaya, the director of Gaza Municipality Library, prefers to say “Life is books”. He tries hard to maintain a good supply of the latest books available on the market.

“If we don’t know our past, we will never understand our present,” he says in praise of the book supply he managed to collect prior to the blockade imposed on Gaza and on the few occasions he has been able to travel. His library, established in 1999, has 22,000 book titles. Of these books, 4,000 books were donated through the Arab states in North Africa. Those books gave a long-awaited boost to Gazas libraries' stocks.

He is frequently at a loss to help meet the demands of readers who ask for books on a wide variety of subjects. “I often get requests for books on human development, science, sports, fiction, history, geography, but I can’t get the supplies through,” he says

In this case, a lack of funding stands in the way - as the high cost of shipping makes it almost impossible for him to purchase books.

“Getting books into Gaza is difficult, but not impossible if you have the money,” he adds as he answers a phone call from a caller requesting new book.

He admits that his connection to international groups like the French Cultural Centre, the British Council and other groups means that he can ask them to bring books into Gaza - the only obstacle is the funding.

“This means that the average person cannot freely order any book he or she wants,” he adds.

As he speaks, in the late hours of the day, a blind student arrives at the library with a request for a specific book on the life of the 20th Century Egyptian singer Mohammed Abdelwahab.

After some searching, Attaya stands puzzled, and disappointed that he must tell the student that he doesn’t have it in stock. He calls the other Gazan and West Bank libraries - but he knows that getting the book, on loan, is virtually impossible.

He grabs his phone and dials the number of the Jenin public library in the northern West Bank, saying: “I have to ask you for a favour.” He explains the situation and both agree to scan 20 pages of the requested book, and send it by e-mail.

Copying pages of books has become a common tactic in Gaza among educators and schools. One textbook makes it through, and in months, through copying, it will be part of the university students' reading list.

Officials estimate that around five million textbooks are required per year, a number that is unbelievably far off for those in Gaza.

When Attaya gets a rare chance to travel outside of Gaza, he doesn’t fill his case with clothes - but as many books as he can carry.

“Books are heavy - but it’s worth the effort,” he says, as he explains how he was able to bring books back from rare trips to Lebanon, the United States, the UAE, Sweden and Cyprus.

“I don’t mind bringing any books, a broad spectrum of topics, even books on Masonic or Zionist ideology are welcome,” he adds.

Out of the wreckage

Yousri Alghoul, a Palestinian novelist and author, says that over the years he has regularly observed Palestinians trying desperatly to maintain and save their existing supplies of books, with people often trying to salvage precious tomes from the ruins of bombed homes. Books represent the freedom to read and learn and make informed choices.

“For me, rescuing a book is more important than clothes or furniture.”

But that does not change the reality in bookshops across Gaza, which have all suffered from a shortage of book supplies and a dearth of financial support for many years. Shayma Badran, 19, walks through the library of al-Azhar University, where, as a student, she can borrow any book she wants, or at least, any book they have in stock.

Wearing a winter coat, she walks by the half empty shelves, thumbing through many of the books which are, by now, long out of date. She cannot find the most recent publications that she needs for her studies.

“I can almost hear the sad, empty, bookshelves apologising for their lack of content - international novels, modern cultural books, anything which broadens and feeds the mind,” she tells MEE.

“I dream of touching an untouched, unread, newly-released novel,” says her friend Marya, as she explores the library. Over the years, she has searched for many books, but “like most youngsters in Gaza, we hear about the latest books and try to participate in the trends of the world, but can never reach them, in our reality,” she adds.

She dreams of reading the Egyptian Pocket novels by Nabil Farouq. “I wish, and dream, that I am reading the Man of the Impossible, and The War of the Spies."

Across from the university compound in Gaza City sits the once-largest bookshop in the town - al-Yajzi Bookshop - which had to resort to selling stationary when book supplies became too difficult to come by. The owner, Hatem al-Yajzi, says: “We have been badly affected by the blockade. Our bookshelves are almost empty of all new titles and modern editions.”

For him, it has become the norm to tell the readers: “Sorry, we don’t have it.”

The bookshop used to participate in several book exhibitions, including the famous Cairo Book Fair, but that is no longer an option given the closure of Rafah Crossing.

In 2012, Gaza was able to have its first book fair involving 37 writers after five years of not being able to organise a book fair.

“Shutting borders negatively affects the lives of intellectuals and students in Gaza,” said al-Yajzi. He knows that, for many in Gaza, books are the only way to escape from a cruel reality, vent human frustrations, or breathe and relax quietly, if only for a while.

Maya sighs and says: ”I envy all people of my age who have access to full bookshelves. I'm19 years old and have never attended a book fair, and all I see here are these empty shelves.”

Maya also understands that radicalism feeds on ignorance, lack of wider knowledge and access to broader options - including the choice, and desire, to read more.

“Reading heals our souls and connects us with the global minds on the other side of the locked down Rafah Crossing gates,” she says, before her friends call her to get back to class.

“We have the right to read, so don’t hold our books away from us,” she adds as she turns back to head to her lesssons.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].