Life among the dead in Egypt's ancient necropolis

CAIRO - In an overcrowded and densely populated city of almost 20 million residents, the very idea of quiet and calm is strange in the Egyptian capital. With the exception of a few elite, high-income neighbourhoods, it's very rare to find a quiet empty street in the middle of the day.

There is one area of Cairo however in which empty streets in the afternoon are a common scene, but that's possibly because not many outsiders choose to wander the streets of a place known as the "City of the Dead".

This small patch of land is a network of old Islamic tombs and mausoleums. Cairo’s old tombs are called “al-Arafa”. Their streets are quiet, narrow, often unpaved, and the tombs encircled by walled compounds.

Some mausoleums are decorated with marble and fountains inside, but this isn’t the case for all of the tombs. Many of them are left crumbling and empty.

Some of the tombs are of famous historical figures, often neglected and abandoned by the government. Muhammed Ali Pasha is considered by some to be the founder of modern Egypt and the remains of his family for instance were laid to rest in Al Basateen Arafa. Although this is considered to be a historically significant site, there is just a lone elderly guard who keeps watch over it. There is no guide or information about the princes and princesses buried there.

These tombs are prone to burglary due to their valuable ornaments and decorations. Many of the residents say that this is because there is no decent security provided by the government.

The necropolis however is not entirely deserted and many families live in this city of the dead. Some inhabit houses they have built next to a tomb or, as is the case for most of the families, they inhabit the tombs themselves. It's hard to find accurate statistics regarding the number of residents but estimates say possibly as many as half a million may live in the tombs of Cairo. However most of these live in the northern cemetery of the City of the Dead, while the southern part is sparsely populated.

Though running water and sewage systems have been introduced to the necropolis, access to them is very limited and is only accessible by a few privileged families there.

The relatively recent phenomenon of living among the dead started when the owners of the tombs would hire a guard to protect the family mausoleum after repeated incidents of burglary. The guard hired was traditionally a young male from a rural area looking for work and accompanied by his wife. Years would pass, the guards would die and would be buried within the same tombs they guarded. The tombs therefore organically witnessed the birth and blossoming of new generations that considered this strange place home.

Now the sons of the owners, and even grandsons in some cases, never visit the tombs, save a few days each year when they want to pay their respects to their relatives or when the family loses one of its members.

There are also individuals who have been forced into the necropolis because of the pressures of overcrowding and the high cost of living that has increased sharply over the years in Cairo.

Strangely enough, there are a few cases in which people actually live in al-Arafa by choice. El Hajj Yasser, a retired gardener in his early eighties who worked with the Ministry of Archaeology for more than 40 years - and managed to build his own six-story flat in Faysal, Giza, where his two sons and three daughters live - refuses to leave the tomb where he has spent most of his life.

He explains to Middle East Eye: “I feel peace here. There are no cars, no street vendors and absolutely no noise.” He continues: “My daughters specifically insist that I move closer to them, so that they can take better care of me, but I will never do it.”

His opinion isn’t shared by most of the dwellers who consider their place of residency a shame, and further proof of their poverty.

Om Fares, in her early fifties, complains about life in al-Arafa. “I was saving money to move from here when the police accused my eldest son of carrying a weapon. Although he was innocent, they sentenced him to three years in prison.”

Amidst her tears, she continues: “I spent the money I saved on a lawyer who promised me that he was going to win the case and get my son out. Now I am doomed to stay here without even my eldest son.”

Day-to-day activities continue here even amongst the dead, and life goes on punctuated by a series of mundane rituals and monotonous tasks. Women wash clothes, prepare breakfast and feed the birds; men drink tea after a long day of work; children play in the empty streets.

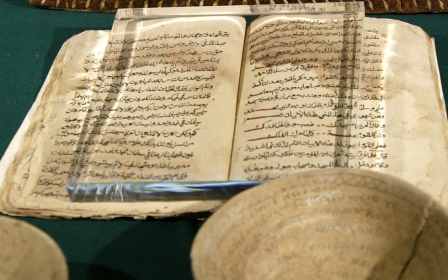

The dead are still ever present. There are many reminders of this, such as when a man is scolded for cursing during an argument with a friend, or the fact that copies of the Holy Quran are visible on almost on every table, and the word "death" is repeated in every conversation as an inevitability of life, and when the children are ordered to get inside behind closed doors by the time of the evening prayer each day.

Abu Walid, who is in his forties, works as a guard of one of the tombs. “Life in Al-Arafa is just like life in any other place," he tells MEE. "It has its good sides and bad sides. It's quiet and peaceful here but only if you're on good terms with your own mortality and learn how to live with the idea that you are amongst the dead.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].