Who should represent the Palestinians?

While serving as UN Special Rapporteur for Occupied Palestine, especially in my early years between 2008 and 2010, I fully expected to encounter defamatory opposition from Israel and ultra-Zionists - what surprised me were various efforts of the Palestinian Authority (PA) to undermine my role at the Human Rights Council in Geneva.

The authority’s representatives exerted various pressures to encourage my resignation, and made unexpected efforts to challenge my reports, especially if they described the actuality of Hamas exercising governing authority in Gaza.

I had the impression that the PA was far more concerned with this struggle internal to the Palestinian movement than mounting serious criticism of the abusive features of the occupation. Since I was trying my best on behalf of the UN to report honestly on Israeli violations of Palestinian rights under international humanitarian law and human rights treaties, I was puzzled at first, and then began to wonder whether the Palestinian people were being adequately represented on the global stage.

Representation at the UN

Among the many obstacles facing the Palestinian people is the absence of any clear line of representation or even widely respected political leadership, at least since the death of Yasser Arafat in 2004.

From the perspective of the United Nations, as well as inter-governmental diplomacy, this issue of Palestinian representation is treated as a non-problem.

The UN accepts the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO) as the sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people, although the reality of Palestinian governance to the PA since the Oslo diplomacy was initiated in 1993.

A similar split between legal formalism and effective authority exists in international diplomacy, although most of the 130 governments have extended diplomatic recognition to the PLO, rather than Palestine, despite its increasingly marginal role in the formation of national and international Palestinian policy in recent years.

This distinction between the PA and PLO is obscure for almost all commentators on the Israel/Palestine struggle, yet it has important implications for diplomacy and the scope and scale of Palestinian representation.

The PA, headed by Mahmoud Abbas, is basically preoccupied with the West Bank and its own political relevance, and has seemed perversely aligned with Israel with respect to the fate of Gaza and even the 5-7 million Palestinian refugees worldwide.

In contrast, the PLO, at least in conception and until the Oslo diplomacy took over, also in practice, conceived of its role to be the representation of all Palestinians, whether living under occupation or as refugees and exiles, that is, as a people dispossessed rather that a territory oppressively occupied.

The Oslo diplomatic fiasco

Among the flaws of Oslo was the delusion that a sustainable peace could be achieved simply by negotiating an end to the occupation of the West Bank, and maybe Gaza and East Jerusalem, and proclaiming Palestine as a state.

This "two-state" international consensus - even after its PLO endorsement in 1988 and incentives provided by the Arab Initiative of 2002 – has been killed by relentless Israeli expansionism and diplomatic rejectionism.

The Israeli rejection of the two-state option, which from a Palestinian perspective was at most a minimalist version of peace, was made manifest over the last 25 years by increasing the inhabitants of the settlement gulag, establishing at great expense an infrastructure of settler-only roads, and through the construction of an unlawful separation wall deep in occupied Palestine.

Yet the more than 20 years of negotiation within this framework served Israel well. It also helped the United States, Europe, and perhaps most of all the PA, to keep its international status credible.

The situation allowed Israel the protective cover it needed to continue annexing, building, and cleansing until a point of practical irreversibility was reached, and thus it has managed to undermine effectively the two-state mantra without suffering the slightest adverse consequence.

This enabled the United States, especially, but also Europe, to sustain the international illusion of a “peace process” while the realities on the ground were making “peace” a dirty word of deceit.

Most of all, this Oslo charade made the PA seem like it was a genuine interim state-building stage preceding existential statehood. In a situation without modern precedent, the PA achieved a weak form of de jure statehood via diplomatic manoeuvres and General Assembly partial recognition under circumstances that lacked any of the attributes of de facto statehood.

Usually the situation is reversed, with the realities of statehood a precondition to its diplomatic and legal acknowledgement. Israel played along with this Palestinian game by denouncing such PA moves as outside the agreed Oslo plan of statehood to be achieved only through negotiations between the parties.

Of course, Israel had its own reasons for opposing even the establishment of such a ghost Palestinian state, because the Likud and rightest Israeli leadership were inalterably opposed to any formal acceptance of Palestinian statehood even if not interfering with Israel’s actual behaviour and ambitions.

Interrogating the Palestinian Authority

Yet there are additional reasons to challenge PA representation of the Palestinian people as we stand on the cusp of a new year. Perhaps, the most fundamental of all is the degree to which the PA has accepted the role of providing security in those parts of the West Bank under its authority, which includes the main cities.

This mandate has been interpreted in Ramallah as warranting the suppression of resistance activities by Palestinians, including non-violent demonstrations and to apprehend those militant Palestinians believed to support Hamas or Islamic Jihad, and then torture those detained in prisons often without charges.

The PA has also consistently leaned to the Israeli side whenever issues involving Gaza have arisen since the Hamas takeover in 2007. Perhaps, the high point of such collaborationist behaviour was the PA effort to defer consideration of the Goldstone Report detailing evidence of Israeli criminality in the course of its 2008-09 attack (Operation Cast Lead) on Gaza. The move was widely perceived as helping Israel and the United States to bury these extremely damaging findings that confirmed the widespread belief that Israel was guilty of serious war crimes.

There have been several failed efforts by the PA and Hamas to form a unity government which would improve the quality of Palestinian representation, but would not overcome all of its shortcomings. These efforts have faltered both because of the distrust and disagreement between these two dominant political tendencies in occupied Palestine, but also because of intense hostile reactions by Washington and Tel Aviv, responding punitively and tightening still further their grip on the PA, relying on its classification of Hamas as a “terrorist organisation” that thus made it ineligible to represent the Palestinian people.

Everyone on the Palestinian side agrees verbally that unity is indispensable to advance Palestinian prospects, but when it comes to action there is a definite show of ambivalence on both sides. The PA seems reluctant to give up its international status as sole legitimate representative and Hamas is hesitant to join forces with the PA given the difference in its outlook and identity.

What should be done

In the end, there is reason to question whether PA claims to represent Palestine in all international venues deserve the respect that they now enjoy.

It is a rather complex and difficult situation that should be understood as part of the Israeli strategy of fragmentation.

This strategy is a deliberate effort at keeping the Palestinian people from having coherent and credible representation, and then contending disingenuously that Israel has "no partner" for peace negotiations when in fact it is the Palestinian people that not only have no partner but not even a credible entity capable of legitimate representation.

Among diaspora Palestinians, I believe there is an increasing appreciation that neither the PA nor Hamas are capable of such representation. It seems that greater legitimacy is attached either to the demands of Palestinian civil society that underlie the BDS campaign, to the imprisoned Marwan Barghouti, or to Mustafa Barghouti, who is the moderate, secular and democratic leader of the Palestinian National Initiative situated in the West Bank.

What these less familiar forms of representation offer, in addition to uncompromised leaders, is a programme to achieve a sustainable peace that is faithful to the aspirations of the whole of the Palestinian people and not compromised by donor funding, Israeli controls and collaborationist postures.

It takes seriously the responsibility to represent the Palestinian people in ways that extend to the Palestinian refugees and to the Palestinian minority of 1.6 million living in Israel as well as to those living under occupation since 1967.

Overall, the picture is not black and white. The PA, partly realising that it had been duped by the Oslo process and that Israel will never allow a viable state of Palestine to emerge, has resorted to more assertive diplomatic positions, including an effort, bitterly resisted by Israel, to make allegations of criminality in their role as party to the International Criminal Court.

Also, it is important that the Palestinian chair at the UN not be empty, and there is no present alternative to PA representation. Perhaps, an eyes wide open acceptance of the present situation is the best present Palestinian option, although the approach taken to representation is up to the Palestinians. It is an aspect of the right of self-determination, which is treated as the foundation for all other human rights.

At the very least, given the dismal record of diplomacy over the course of the last several decades, the adequacy of present representation of the Palestinian people deserves critical scrutiny, especially by Palestinians themselves.

- Richard Falk is an international law and international relations scholar who taught at Princeton University for 40 years. In 2008 he was also appointed by the UN to serve a six-year term as the Special Rapporteur on Palestinian human rights

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

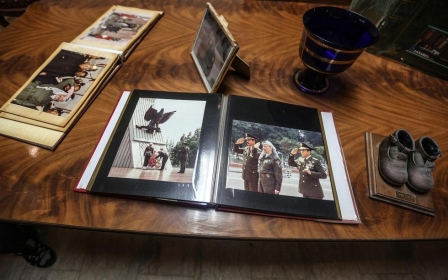

Photo: Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas, during his arrival at the Greek parliament in Athens on 22 December, 2015 (AA).

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].