Aleppo’s heavy metal bands tour Europe, but not the way they hoped

AMSTERDAM - Syrian heavy metal singer Adel Saflou asked Middle East Eye to meet him at a maximum security prison in Alphen-aan-den-Rijn - the temporary housing provided to him and other refugees in the Netherlands, where he was writing his new album.

Bearded and balding, with eyebrow and nose rings, Saflou carries both the toughness of an ageing rocker and the sweet charm of a small-town student. Now 22, he’s writing lyrics for his band, Ambrotype, from a prison cell overlooking a closed yard where dozens of Syrian, Iraqi, Afghan, Yemeni and other refugees play football.

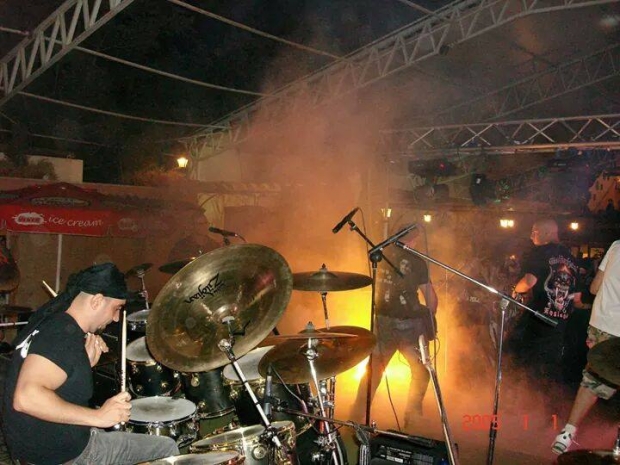

“When I was in Aleppo during the war, we were doing one festival or concert a month," Saflou told MEE. "We had a really big following and a lot of people showed up, thankfully. The scene was bursting with life. Everyone was happy. It was a major form of escapism for everyone. I was there until the end of the scene, of what I mark as the end of metal in Aleppo.

Bashar Haroun's U.Ground events company put on major concerts and festivals in which the bands headlined. "We finished the last U.Ground concert, that big festival, and I never expected that this would be the last gig I ever (did) in Syria. It’s really heartbreaking to know that I can’t play in Syria again.”

Growing up in Idlib, Saflou collected heavy metal and rock music, artwork and books. His love for loud, rebellious and forbidden music drew him and others to cluster in the underground clubs of nearby Aleppo. Youth who were on the fringes found doom, death and thrash metal as an outlet to help them cope with the growing violence.

The songs allowed them a covert way to criticise warlordism and fanatics who claimed holiness as they killed, or let them sing with biting honesty about heartbreak, as well as to forge some distant link to the European metal scene they dreamed of touring.

In Aleppo, Saflou teamed up with concert producer Bashar Haroun and his best friend, guitarist Jawdat al-Atasi, to perform as Orchid, a melodic metal band that combined dark, powerful guitar with choral vocals. What a rush it was for him to sing Such a Creep, a song about a man who realises he’s no good for the girl he loves, to a crowd in a city where metalheads could be arrested and harassed, while several armies were battling to take over the city around them.

But while Saflou was performing with Orchid, his home town of Idlib was partly taken over by Jabhat al-Nusra, the Syrian al-Qaeda affiliate, and one of their units moved into his family’s house.

One neighbour told him by phone, confirmed by a family member, that when the fighters found his teenage bedroom full of metal fan books and art, they claimed it was Satanic literature and told the neighbour that if they found him they would cut off his head. The family had to tell the fighters that Saflou had left long ago and was no longer part of the family to save themselves.

Meanwhile, in Aleppo, the war finally divided the city, causing Orchid and other bands to fall apart as their members were forced to flee. Saflou and many of the others couldn't go home, thus began Syrian metal’s exodus. Some, like Haroun and al-Atasi, headed for the government-controlled coastal town of Latakia and continued running concerts. Saflou and many others fled to Lebanon where he began recording for pioneer Rudi Messih’s Arab metal project, Rasas, meaning "bullets".

But when more news came out about militant groups murdering musicians, banning music and carrying out public whippings and instrument smashing, Saflou, al-Atasi and many peers realised they would be continually threatened and, with still more troubles in Lebanon and Turkey, headed on the “death boats" to Europe.

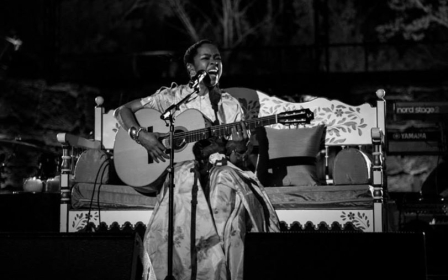

As Monzer Darwish, a Syrian filmmaker, musician and friend of Saflou, explains in his upcoming feature documentary film, Syrian Metal is War, the Middle East’s long-misunderstood metal bands and their fans, especially in the war-affected areas, represent something far more symbolic about the fate of the Middle East than simply a music subculture.

Outside the relatively softer and more public Damascus groups like Anas & Friends (now Khebez Dawle), Gene Band and Tanjaret Daghet, who mostly fled to Lebanon and quickly got media and some support, there are these doom, death and progressive metal bands like Ambrotype, Orchid, The Hourglass and Eulen who faced even more threats and attacks and became magnets for youth who refuse radicalism and, in most cases, refuse to fight.

Political and religious leaders claim holy virtue as they conduct war and condemn these youth for their dark arts. But these youth, who see their growls, moshing, and skull art as something akin to Shakespeare’s murder classics or Hollywood horror films, condemning evil by making artistic thrills out of it, represent arguably the Middle East’s most dedicated anti-extremist subculture.

But in the end, armed groups proved more powerful than unarmed youth, and attacked some of them, including Darwish, who was beaten over the head and left for dead, and forced most of them to flee the country. Now they are arriving in the Netherlands, Germany and Sweden, applying for asylum and wondering how to rebuild their music scene in exile.

Darwish, in his own complex journey of survival, survived filming on the front line and made it with his wife all the way to the Netherlands this past summer. Since Darwish had been directly attacked and was launching a risky film, he moved easily through the Dutch system and won asylum. This writer joined Saflou on a reunion trip to meet Darwish to talk about the film, and Saflou’s part in it.

“When I was in the camp, I heard about these Paris attacks and it was the day after they happened," Saflou told MEE. "I was like, oh my God, now there's going to be a backlash against us. They’re going to be really cautious when they’re dealing with the new people coming as refugees.”

The Dutch, like other EU governments being pulled by pro- and anti-refugee lobbies, had offered Saflou and thousands of other newly-arrived refugee applicants a stressful, confusing mix of good and bad news.

Some would stay in basic rooms in the global city of Amsterdam. Others would be rotated around rural, sometimes isolated, housing centres all over the country, and still others would stay at Alphen prison. Sometimes, like in Alphen prison, they had a private room for two with a desk and a TV, a football yard and music room.

Other times they would be piled together in a large military dorm mixed with women and men of all ages sleeping beside each other. More comfortable perhaps than the migrant camps on the route from Greece to Serbia, or the notorious Jungle settlement in Calais, France, applicants still risk having their belongings stolen, or being harassed or threatened by other applicants.

Some groups stood together to protect each other, watch valuables and send each other messages if their names or some urgent announcement were posted on the board while they were staying in town.

While some got interviews and decisions within a month or two, others waited well over a year. Not permitted to work, that meant borrowing from people back home living in a warzone, or finding work off the books.

It became routine for applicants to meet up to see their friends in Amsterdam or Utrecht or The Hague, one having won legal asylum, another in-process, and another denied and told to leave the country. They compared notes, spent the few euros they had on fast-food falafel or cigarettes, and then sent selfies back home of them smiling on a canal bridge, or posing in a sarcastic grin in the red light district.

But all the while, Saflou continued to develop his sound, now influenced by his new surroundings.

Saflou stops at the Alphen riverside, watching Dutch barges pass by in the cold night as he explains his unusual blend of prog rock, prog metal and jazz band. "I’ve been trying to mix the three genres in a way that hasn’t been done before. I’ve been trying to get some oriental, twisted, really evil-sounding scales on there which are influenced by my Syrian background, but not in a cheesy way."

"I think Ambrotype is my whole life’s video, documentary or whatever. If you listen to Ambrotype, it talks mostly about my life, the things I’ve been to, the war I’ve witnessed. Even though they’re all metaphoric, you can still get an idea. What I’m trying to do with Ambrotype is influence a lot of people, make them feel something.”

With the Aleppo metal scene spreading outward from its Syrian origins and many musicians coming to Europe, what destroyed these musicians’ families and lives has opened new artistic possibilities.

While death metal/growler producer Bashar had to shift U.ground to the coastal city of Latakia and then wanted to teach music to youth, it also meant he had to bring his students’ style of music to the festivals he still runs in Syria. Al-Atasi ended up in Italy and Darwish in Amsterdam. All of them suffered huge losses, and a lot of pain, while at the same time having doors opened that were not expected. Most of them still feel a sense of eternal comraderie, and that includes Saflou.

However, now that Saflou is forced to rebuild his music in the Netherlands, he no longer feels like Syrian metal has to be hardcore, or even played only with Syrians. He had to shelf Orchid, left Messih’s project Rasas, and abandoned his heavy growl for the most part, in favour of his current project, Ambrotype. Why not invent some new Syrian-Dutch metal jazz hybrid? Country and life in ruins, at least musically, he now feels free.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].