Egypt’s low-key 25 January protests don’t mean Sisi is secure

It would be tempting to view Monday’s anniversary protests in Egypt as a complete victory for the country’s military-backed government and its president, Abdel Fattah al-Sisi. Such a view would be shortsighted, however, because the protests should be viewed in a larger context.

It is true that Monday’s protests - marking the five-year anniversary of Egypt’s democratic uprising - appeared significantly smaller than previous pro-democracy protests. But the fact that marches were held in several governorates across Egypt - in spite of the threat of imprisonment or death - is a testament to how serious some in Egypt still are about completing their revolution.

Also, and importantly, the palpable fear displayed by the regime in the lead-up to planned protests demonstrates the extent to which protest and dissent remain concerns. In the lead-up to Monday’s planned protests, Sisi’s government employed serious, arguably extreme and irrational, security measures.

The regime’s fear was first put on display last month when Sisi delivered a speech warning Egyptians that planned 25 January protests could “ruin” Egypt. Even pro-regime media figures appeared taken aback by Sisi’s apparent panic. As Tamer El-Ghobashy reported, prominent pro-regime broadcast personality Yousef Al-Hosseiny asked, “Why appear nervous or worried?... Who really benefits from such a scenario where the state is depicted as worried or nervous?”

This past weekend, the regime arrested dozens of Facebook page administrators, and began randomly raiding homes to check social media accounts for signs of opposition. Consistent with their policy of using religion as a tool of repression, the regime also instructed Imams to use religious sermons to warn Egyptians about the harms of protests. Additionally, in the hours before Monday’s anniversary protests were set to begin, security forces arrested an American who was reportedly heard talking about “the revolution” in a coffee shop. On Sunday, the metro, which has been used as a tool by anti-regime protesters, was shut down by police.

Perhaps most tellingly, in the days leading up to Monday, the Sisi regime set-up security walls around the major squares - most notably, Tahrir Square, the key site of the 2011 uprising. A line of military tanks was set up around Tahrir as a bulwark, ensuring that unwanted parties would be prevented access. In the lead-up to Monday, the scene looked more like a potential war zone than a potential protest site. Consistent with its “no protest” policy, the government arrested at least 150 people across Egypt on Monday.

The regime is perhaps rightly worried about protests and dissent. The regime knows that the Muslim Brotherhood - although all but eliminated from public life - remains popular, as do other secular revolutionary groups. Although it projects Sisi as universally popular, the regime is likely aware that scientific polling data show that post-coup Egypt is a split society, with roughly half of Egyptians rejecting the 2013 military takeover.

The regime must also be aware of increased public dissatisfaction with the government among non-Islamist Egyptians. Growing dissatisfaction in a country like Egypt - where citizens have demonstrated on multiple occasions their willingness to die for freedom - can be a recipe for the political demise of a regime. Sisi knows this - during his campaign for president, he expressed awareness that people could revolt if polices proved ineffective.

Moreover, and in any case, history should make any Egyptian regime fearful of protests. It was, after all, a large protest that created a spectacle from which Hosni Mubarak, Egypt’s dictator from 1981-2011, could not recover. He was forced to step down after 18-days of large nationwide protests broadcast on global television. The same was true, but differently so, for Mohamed Morsi in 2013. Egypt’s first-ever democratically elected president was ousted by a military coup, but he, too, was subject to large nationwide protests against his governance.

The current government has learned from the past and decided that it must, at any cost, prevent public spectacles. The regime forcibly dispersed large anti-coup protests at Cairo’s Rabaa and Nahda Squares in 2013, killing at least 900 protesters with live ammunition in a matter of hours. In all, the regime has killed more than 2,500 people, nearly all protesters.

In late 2013, the government passed a draconian protest law that effectively criminalises protests. More than 40,000 people have been arrested, many for either illegally protesting or “inciting” protests. Although Islamists have borne the brunt of government repression, the regime has gone after prominent secularists and NGOs as well.

Sisi is firmly entrenched for now - he has the support of the military, police, judiciary, and media, as well as key international diplomatic support - but he is also working against the clock.

He has promised an economic revival, and failure to deliver will lead to public anger. So far, the economic results are unfavourable.

As Professor Emad Shahin has recently documented, Sisi’s prized economic project — the Suez Canal expansion — has, to this point, been a stunning disappointment. Not only has the canal expansion not produced the type of dramatic revenue increases promised by the government, there has been a decrease in revenues. As Shahin notes, canal revenues were “$48 million lower in August 2015 than in the same month a year earlier”. More ominously, perhaps, Egypt’s real GDP is growing only incrementally, while inflation continues to rise dramatically.

Sisi has also failed to deliver on his biggest policy component - security. In his presidential campaign, Sisi positioned himself as a strong-armed military man uniquely positioned to fight terrorism. Since he has taken over, however, terror attacks in Egypt have increased manifold. A recent report by an independent American Think Tank, The Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy, suggests that “more [terrorist] attacks are occurring than ever before”.

The report also suggests that attacks are more organised and occurring “in more locations throughout the country” than at any other point in modern Egyptian history. The think tank’s quantitative analysis revealed that there were 30 attacks per month in 2014 and more than 100 attacks per month from January – August 2015. The report notes comparatively few attacks during the one-year Morsi presidency, which ended in July 2013.

For Egypt, the economic and security issues are deeply intertwined. If Egypt does not restore some semblance of stability, tourists - a key source of revenue - will not return to the country. Egypt’s tourism industry had already been suffering when, last October, ISIS brought down a Russian passenger jet. Egypt’s Tourism Minister recently announced that the country has been losing $283 million per month since the crash. Egypt’s handling of the crash has also failed to inspire confidence. As the New York Times has documented, the Sisi government has resorted to conspiracy theories to explain the crash - in spite of an evidence-based international consensus that the crash was caused by terrorism.

Going forward, it can be expected that the Sisi government will continue to be heavy-handed in its dealings with dissenters, particularly, and especially, if its policies continue to disappoint. This “iron fist” approach is likely to work, unless, or until, enough of a critical mass develops that heavy-handedness becomes self-defeating, as was the case during the 2011 uprising. As I wrote in an earlier article, this is perhaps a matter of when, not if.

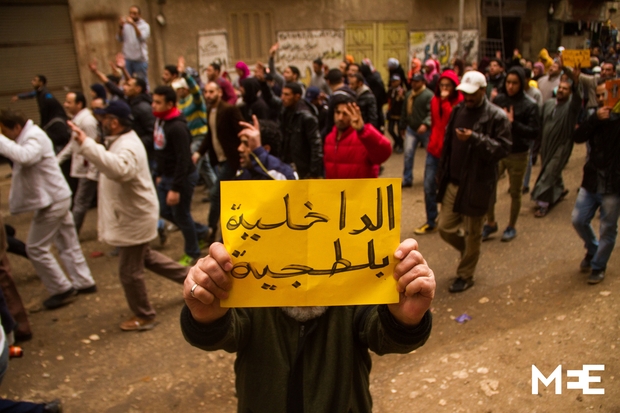

Image: 'The interior ministry are thugs,' says one sign from Monday's protests in Giza (MEE)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].