Do Christians really have a raw political deal in Lebanon?

Christian politicians in Lebanon have raised a series of demands that concern the political status of the community. These sectarian claims date from 2005 when the Syrian forces left Lebanon and the Christian political movements that had been previously persecuted by Damascus (1990-2005) were incorporated in political life.

The Christian political agenda in Lebanon is usually set by Maronites, the largest Christian community in the country, who claim to represent the interests of all the Christians denominations of the country. Which are these claims?

First of all, Christian parties believe that after the 1989 Taef Accord their community lost much of its rights. It is true that Taef, which brought an end to the civil war, also signalled the end of Christians’ political dominance in Lebanon. The president of the republic, a Maronite Christian according to the country’s power-sharing system, was deprived of critical prerogatives such as the nomination of the prime minister and the various ministers, the firing of ministers and the dissolution of parliament before the expiration of its term.

These prerogatives curtailed or transferred to the prime minister and the cabinet after Taef, altering the institutional balance in favour of them. The Taef Accord also changed the confessional balance in parliament, changing the 6/5 formula in favour of Christians in a parity between Christians and Muslims. The same modification also took place in staffing the state apparatus.

Nevertheless, Christians are allocated half of the parliamentary seats and those of the cabinet, despite the fact that they constitute about a third of the population. What is more, high official posts such as the president of the republic, the Chief of Army Staff and the governor of the central bank are always held by Christian Maronites.

The second Christian claim is that Christians are deprived of the offices that are assigned to them according the country’s power-sharing system. This argument concerns mainly the office of the president of the republic. Christians stress that as the Sunnis nominate the prime minister and the Shiites the parliament’s speaker, Christian parties should have a strong say on the election of the country’s president.

The president, according to this rationale, should have strong political backing from the Christian community, a condition that makes him a strong President, and one who can successfully fulfil his duties. This demand is supported form Christian parties across the March 14/ March 8 divide. However, this argument should be turned into a question. Initially, it turns the presidential question from a Lebanese to a strictly Christian one. However, in a consensual political system like the Lebanese one, the president must represent the unity of the nation and not strictly the interests of his own community.

Regardless of the support that he may enjoy from his own community, a Christian politician who is not on good terms with the other communities cannot play this role. Let’s remember that Suleiman Franjeh had a strong backing from the Christian community, but his bad terms with Muslim politicians didn’t allow him to manage the country’s affairs and prevent the ensuing confrontation.

In contrast, Fuad Chehab didn’t have a strong political backing from the Maronite community. Nevertheless, he managed to promote a reformist agenda and strike a fair balance between the Christian and Muslim communities. For this reason ex-prime minister Fouad Siniora stressed in a meeting with the Maronite Patriarch that “a strong president is not a partisan one, but one who can unify all the Lebanese and exercise wise leadership”.

Furthermore, Muslim sects don’t necessarily nominate the candidates of their preference. It depends on the balance of power in the parliament. In 2011, Najib Mikati was nominated and then elected prime minister without the consent of the Future Movement, due to the new majority that emerged in Parliament after the alignment of Walid Jumblat with the March 8 block.

The third Christian concern is the electoral system. Christian politicians claim that in many cases Christian populations are integrated in electoral districts with a Muslim majority, a condition that allows Muslims to determine the Christian parliamentarians of this district. According to this argument, this practice produces an electoral result that is not representative of Christians’ political preference.

In order to address this situation, Christian parties support the adoption of 15 electoral districts and proportional representation, modifications that would produce a fairer result. Indeed, the current electoral law permits Muslim parties to elect Christian MP in districts such as Akkar, Alley, Chouf and Zahrani, allowing the Future Movement to elect eight Christian MPs and the PSP five, stressing only the most significant examples.

However, Lebanon is a country with a Muslim majority. At the same time, the Taef Accord provides for equal representation between Christians and Muslims, a fact that leads to the inclusion of Christian seats in districts with minor Christian populations. As the Boutros Commission stressed, “the elements of fair representation in the sense of confessional ‘control’ and ‘equality’ could not be achieved together, but that a compromise would need to be found to respect both principles as much as possible”.

Far from being disenfranchised, Christians in Lebanon still exert considerable influence and are over-represented in correlation with their population. The sectarian claims adopted by Christian parties reveal that they have not adapted themselves to the facts of the post-war era, namely the loss of the political dominance that they had exerted previously.

- Yiannis Plakas is a political analyst interested in Middle Eastern affairs based is in Volos, Greece. You can follow him on Twitter @iplakas

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

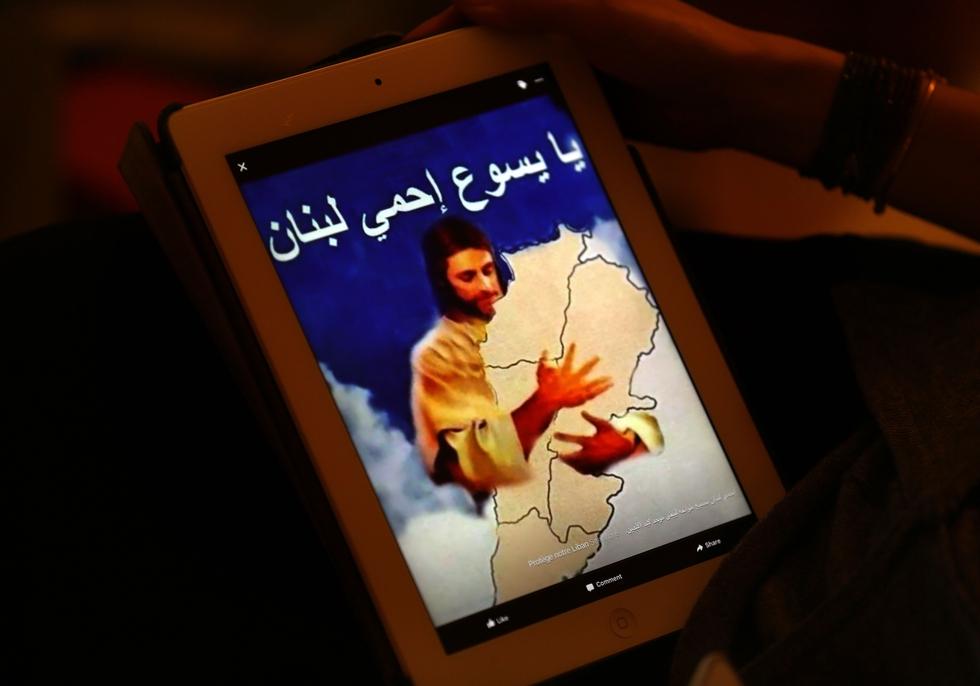

Photo: A woman holds a tablet displaying an image, shared on social media, of Jesus holding a map of Lebanon and reads in Arabic "O Jesus, protect Lebanon" in the Lebanese capital Beirut on 24 December, 2015 (AFP).

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].