Beirut's movie archivist preserves Lebanon's celluloid glory years

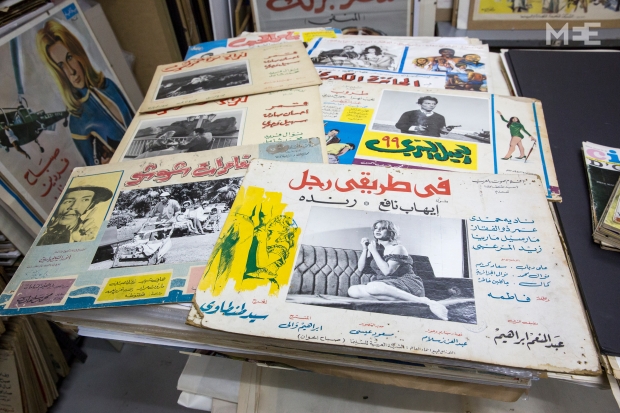

Located in the basement of an apartment block in Beirut’s Hamra district, behind endless shelves of Arabic language books, is a small back room that’s a shrine to the cinema of the past. With its neatly stacked piles of posters, it is one of the Arab world's most comprehensive collections of film paraphernalia, with vibrant posters and photographs of actors lining every inch of the walls.

This treasury of half a century of Arab cinema is the work of one man. Abboudi Abou Jaoude, a Lebanese publisher and himself an encyclopedia of cinema, has been collecting film posters since he was 15.

In December 2015, Abou Jaoude released the book Tonight – a comprehensive guide to movies filmed in Lebanon from 1929-1979, narrated through posters, photos and articles. The book is the culmination of his hobby-turned-passion, the result of decades collecting posters and building an archive of Lebanese cinema.

From the office of his publishing and book distribution company Al Furat, dressed soberly, a pair of spectacles hanging around his neck, Abou Jaoude nods towards an Arabic poster printed in Cairo for 1940 British production The Thief of Baghdad directed by Michael Powell. “It was the first movies that tried bluescreening and was so popular around the world that it was re-shown for more than 30 years after the filming, especially in Arab countries,” he says, his face lighting up.

Hanging on another wall is 24 Hours to Kill in Beirut – a Beirut-printed poster of a 1965 American production showing a pilot drawing his gun on an unknown assailant. Egyptian bellydancer legend Nadia Gamal dances in the background. “There were around 25 French, English and American movies shot here in the 60s and 70s,” Abou Jaoude says. “They were mostly B-movies though, and some even C or D,” he laughs.

Other posters feature music icons of the Arab world – Fairuz, Sabah, Soad Hosny, Farid Al-Atrash – recalling an era when they were among cinema’s biggest stars.

At the age of 15 Abou Jaoude started collecting posters of his favourite actors like Clint Eastwood and Steve McQueen, soon adding films featuring iconic Arab singers. His collection is now made up of around 20,000 pieces and sheds light on the Arab world’s cinema heritage through posters from the Levant and North Africa, film stills and Arab cinema magazines.

Though TV networks such as ART, Sabbah Brothers and Rotana own the rights to many Arab films from the past, some footage was lost or destroyed during Lebanon's 15-year civil war or through a lack of adequate archives. In some cases the only proof that these films existed is a poster that once hung in a cinema lobby whilst it screened.

“There were some Lebanese and Arabic movies that I couldn’t find any information about. No archives existed, so 10 years ago I began to make one,” Abou Jaoude says.

Discovering that the records of films produced in Lebanon with the Ministry of Culture and other sources were not only incomplete but “inaccurate”, Abou Jaoude made it his mission to fill in the blanks.

“The book is important because it is done with professionalism and all the films produced are mentioned. Abou Jaoude wanted to be exhaustive,” says Antoine Khalife, director of the Arab programme at the Dubai International Film Festival and special advisor and producer for ART, who moderated a talk around Tonight during its launch. “It’s aimed at a large audience. The book can be enjoyed equally by the cinephiles, movie lovers, but also the wider public.”

A vintage cinema poster collection

On one wall of Abou Jaoude's office a poster for 1938 film Yahya el Hob” (Long Live Love) shows an intricate painting of Egyptian singer and composer Mohammed Abdel Wahab, with actress Layla Murad – fluid notes float along a musical notation wrapped around them. Abdel Wahab pioneered the Arab musical-comedy with eight films made between 1933 and 1949: it became one of Egyptian cinema’s most popular genres.

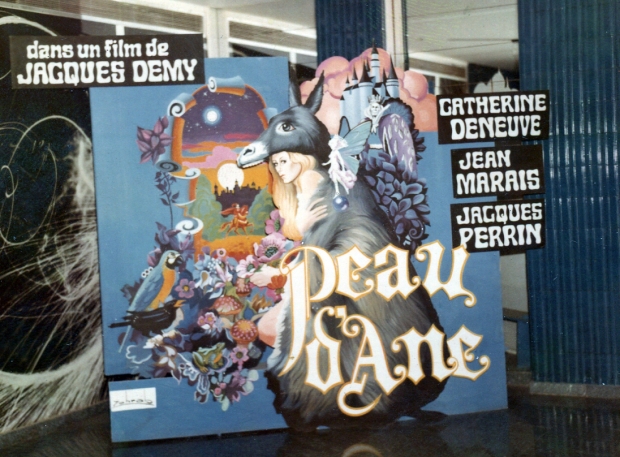

The hand-painted posters vary in style and quality. Some are impressively detailed, others feel more rushed – perhaps banged out by a lowly-paid artist on a short deadline. They show Lebanese productions that cover every genre from spy thrillers showing gun-wielding villains and half-naked women, to romance, with two characters locked in passionate embrace.

According to Abou Jaoude, many artists didn’t have their own style, taking inspiration from American posters. They do, though, show a freedom, where “everything goes”. “From them we can study the time, the sociology, everything,” he adds. Khalife believes the posters show an idyllic world of escape. “They [tell] the dream and fantasy that producers wanted to push spectators to believe. The posters tell us about the liberty, the joie de vivre, far away from the real problems in Lebanese society.”

From the early to mid-60s most Lebanese movie posters were made in Cairo, but with the nationalisation of Egyptian cinema under President Gamal Abdel Nasser, many producers flocked to Beirut and the industry followed. The mid-60s to mid-70s is considered Lebanon’s “golden age” of cinema, with around 35-40 films made every year at its peak, according to Abou Jaoude.

“The most beautiful posters are from the 40s to the beginning of the 60s, with works from artists such as Jaissour, Abdel-Rahman, Abdul Aziz Hawarian and Zohrab,” Abou Jaoude says. “Later on the work was of less quality. Studios and producers didn’t want to pay.”

The daily grind of a film poster painter

“I painted maybe thousands of film posters and worked in [the industry] for 16 years,” says Lebanese-Armenian painter Krikor Zohrab Keshishian, from his Beirut atelier, drinking morning coffee with friends from the neighbourhood, perched inbetween half-finished canvases.

Now a well-regarded artist in his early 70s who has exhibited around the world, Keshishian started his career painting cinema posters in a commercial art atelier in Aleppo in 1956 aged 13. He worked under Greek-Syrian artist Serios, before moving to Lebanon in 1962 to work at the gallery of Lebanese-Italian painter and caricaturist Juliano Achkar.

In the days before the digitisation of graphic design, each cinema poster, no matter how large, was painstakingly painted by hand. It was a job defined by long hours, low pay and slave-driving bosses. “We worked like donkeys. We would paint very big posters for the cinema front in two days, working through the night. We were paid nothing,” Keshishian says. The going rate was one Lebanese pound per one sheet (before the war $1 equalled three Lebanese pounds.)

The posters were often so big that they wouldn’t fit in the atelier and the only way to work was by rolling up the canvas as they painted; plywood posters were worked on in individual blocks, and pieced together later.

One of the biggest Keshishian painted was a 50m by 60m poster of 1967 film To Sir, with Love starring Sidney Poitier, for Piccadilly Theatre. For most of his career, Keshishian was a ghost painter, signing under the name of the gallery boss. It was only upon opening his own atelier in 1968 that he started signing “Zohrab.”

Though he couldn’t afford a camera, Keshishian paid a photographer to take photos of his works and he still has an impressive record. One black and white photo shows Beirut’s Empire Cinema with his billboard poster for Bond film Goldfinger, a hyped crowd gathered outside for its opening night.

His works include posters for Arab film stars such as Faten Hamama, Mahmoud Yassin and Rushdy Abaza, along with Hollywood giants like Gregory Peck and Ingrid Bergman.

“I’m glad I have some photos of that time. This is history,” he says. “Today I appreciate it more. I worked with my heart.”

After painting his final film poster in 1972, Keshishian had his first solo exhibition of his own work at Beirut’s Bristol Hotel. He was invited to Venice in 1975 to make a large painting for a church and left a few days after the start of Lebanon’s Civil War.

The trials and rewards of an obsessive collector

For Abou Jaoude, it’s meeting people such as Keshishian that has made the journey into Lebanon’s cinema history so interesting. “It’s an enjoyment to know there are many people who love the poster work,” he says. “I’ve met older people who once worked on these films and have kept posters for years.”

During research for his book, Abou Jaoude met Ibrahim Takkoush, a Lebanese director and actor who made a handful of films in the ‘50s including “Lastu Muthniba” (I am not Guilty). Abou Jaoude says he now sells flowers on the street of Hamra, close by to the old cinemas where his films would’ve once screened. He’s just one example of the fate-changing reality of war and an industry that was brought to its knees in its booming years; halting promising film careers along the way.

It has taken Abou Jaoude decades to piece together information about Lebanon’s cinema history and he’s travelled throughout the Arab world, visiting the old cinemas of Syria, Egypt, Iraq and Morocco, to track down missing posters.

“It’s a puzzle,” he says. “I found some Lebanese and Syrian movie posters in Morocco that I couldn’t find here, Lebanese films in Egypt and Egyptian films in Lebanon.” Abou Jaoude knows of a handful of other film poster collectors in the region.

Though they mostly focus on a specific actor or theme, demand means prices for rare posters can be high. The most he ever paid was $1000 for the poster of 1933 Egyptian musical Al Warda El-Baida (The White Rose), starring Abdel Wahab. Though having not seen another copy resurface since, he has no regrets.

The importance of archives

With no comprehensive national archives in Lebanon and a similar situation in the wider region, many private institutions and individuals have had to step in to save its cultural heritage from being lost to history. Associations such as the Foundation for Arab Music Archiving and Research (AMAR) and The Arab Image Foundation (FAI) are working to create publicly accessible archives.

For Khalife though, creating a national archive remains essential. “The private institutions are important and they are doing a great job but national archives should exist and the Ministry of Culture should be involved in this,” he says. “Unfortunately, they don't realise how important the cinema is. It's impossible for private initiatives to work on the archives. They don't always have the necessary finance to continue.”

In the meantime, Abou Jaoude is keen to continue sharing Lebanon’s cultural legacy with the public. "Most of the younger generation don’t have any idea what we did in the 60s and 70s. I want to show them the culture we had,” he says.

With a recent exhibition of his poster collection at Zaitunay Bay attracting over 100 visitors a day, it is certainly resonating with people.

Going forward, Abou Jaoude hopes to take his exhibition to Lebanon’s other cities and envisions a future cultural centre where his archives will be open to the public. “The archive is the life of the people and the continuation of life,” he says. “It’s our past culture and people should see it.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].