Journey to Aleppo: How the war ripped Syria's biggest city apart

ALEPPO, Syria – Before the war you could have a leisurely breakfast in Syria’s capital Damascus and be in Aleppo in time for a late lunch at one of its famous restaurants.

Today the fast, direct route has been cut. For several weeks this winter, the government-held areas of Aleppo were completely isolated as has often been the case since the conflict began. Thanks to recent Syrian army successes the route has been reopened, but the journey involves long and sometimes unpredictable diversions.

We made the first leg of the journey, the 160km drive north from Damascus to Homs, with no difficulty, pausing on the way to pick up a Syrian army lieutenant, Ali. The 22-year-old officer was returning to duty after eight days leave. He told us how he had abandoned his university engineering course three years earlier to volunteer for the army.

It was more than two years till Ali saw his parents again. He was assigned to the defence of Kweiris military airport to the east of Aleppo. Ali spoke of daily battles against the Nusra Front, al-Qaeda’s affiliate in Syria, and more recently Islamic State opponents.

The airbase was inaccessible by land, so the soldiers were supplied with ammunition and supplies by helicopter. When Islamic State joined the siege in the summer of 2014, it brought sophisticated weapons that could shoot down the helicopters. Thereafter supplies were dropped by parachute from planes. Often they drifted off target and were by picked up by the rebels. When Ali was struck in the chest by a bullet there was no evacuation. He spent 15 days convalescing inside the fort before returning to the fight.

He said of IS: “They are non-humans. They are not afraid. They are not affected by injuries. Some say they take special drugs.

“They have more men than Nusra and they are more ferocious. They must maim the corpses of those they kill or they do not believe they are dead.

“When we catch them we find ammunition, dates, drugs and ladies underwear for the virgins waiting for them in heaven.”

Ali took out his mobile phone and showed me footage of gun battles against Islamic State opponents who he said were just 75 metres away.

“The secret behind Kweiris was the loyalty of the soldiers. We had no tanks but stood fast over four years. I lost 82 comrades,” Ali said.

The siege was lifted late last year, in a signal that the tide has turned in favour of the government of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, who has been supported by Russian air strikes since September last year.

Ali is now involved in mopping up Islamic State positions around al-Bab, a town east of Aleppo which many say is more important in military terms to IS than its Syrian headquarters in Raqqa because of its proximity to Aleppo.

The road to Raqqa

I had been wanting to travel to Aleppo for more than a year, but was unable to make the journey because I was told it was too dangerous. This changed at the start of the year as Syrian government victories meant that there was a safe road into the city.

In the old days, the direct route to Aleppo would have headed through Homs to Hama but these days there are many diversions along the way. To reach Aleppo now, one has to turn onto the road headed for IS-held Raqqa and drive directly along it.

Our driver, Abdullah, made the journey several times a week and was very experienced. This was essential: one error of navigation can lead you to an Islamic State or al-Nusra checkpoint.

Abdullah said he had owned a textile business in the old city of Aleppo. When his house and business was destroyed, his car was his only remaining asset. “I had to face reality. I became a driver,” he told Middle East Eye.

It meant a loss of status. “At first I found it hard to being called ‘the driver’. It’s a job at the end of the day and I am not ashamed,” he said.

Abdullah told me what he has faced on the road: the roadside bombs; being caught up in clashes; fake checkpoints manned by insurgents or criminals. “They loot you or they sell you for ransom.”

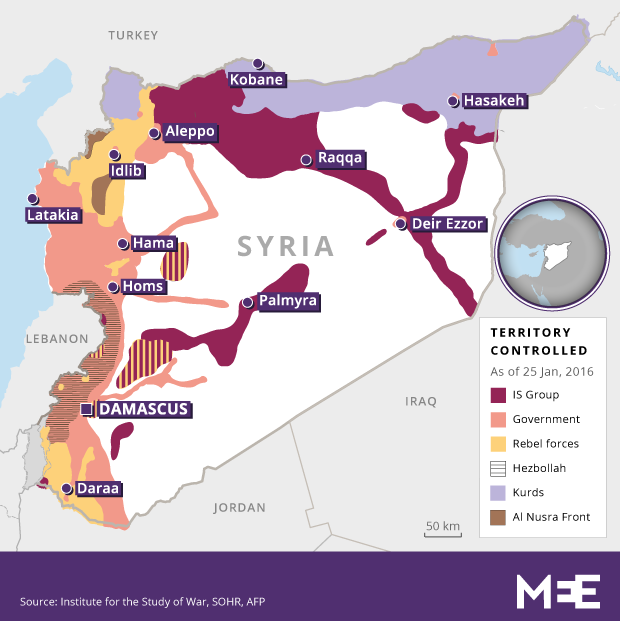

We were now in bandit country. The driver said that al-Nusra positions started just a kilometre or so to the north while Islamic State was to the south. There are frequent checkpoints and many improvised roadside forts, artificially raised areas that are all well-armed, with a panoramic view of the surrounding countryside.

Between the checkpoints Abdullah drove at breakneck speed. Then, to his frustration but my relief, we found ourselves marooned behind a military convoy. A soldier stood at the back of the final truck waving his machine gun menacingly at any car which came to close. Though I had no way of telling, my companions told me that the convoy contained Russian as well as Syrian troops. Moscow has stepped up its military presence inside Syria in recent months, but it has been reported that its troops were concentrated in the western provinces.

Eventually we turned north. I watched shepherds herding their goats as the sun set behind a range of low hills, and fell asleep. When I woke up it was dark and Ali had been dropped off. We had arrived at the entrance to Aleppo. Though there was no street lighting, and the apartment blocks were dark, through the darkness I could see the destruction all around.

Entering Aleppo

Less than four years ago, Aleppo was a prosperous and beautiful city. Christians and Muslims lived side by side, as did Sunni and Shia. A tolerant culture was sustained by a massive industrial centre. Aleppo’s dynamic business community had developed thousands of factories in the industrial suburb of Sheikh Najjar, which employed one million Aleppans.

Inside the city there were some of the greatest treasures of world civilisation: ancient churches, mosques, the famous covered market and the incomparable citadel in the heart of the city.

Almost everything has now been destroyed. In Damascus, the Old City survives but many of the suburbs lie in ruins. In Aleppo, the centre has been gutted, and much of what remains is in the hands of rebels.

A journey from the east of the city to the town centre used to take half an hour. Now it lasts a day, and sometimes much more because of the road blocks and checkpoints.

For the last few years the government has ruled over the western parts of the city, while a collection of rebel forces have dominated the east.

Many government areas are under regular mortar bombardment. Some of these attacks involve small mortars which inflict localised damage. The pockmarked city landscape reveals how the rebels are now using improvised gas canisters, more like missiles than conventional mortars. These can bring down buildings or cause carnage if they land in a crowd. Aleppo’s remaining hospitals are on permanent standby for an influx of mass casualties – 100 or more at a time. These lethal weapons can fall anywhere.

They are one reason more than one million residents have fled. Meanwhile, in rebel-held areas human rights groups accuse the Syrian government of pummeling the city from the sky and dropping so-called barrel bombs that are often filled with shrapnel that can rip through human flesh with ease. Amnesty International has called the widespread use of the bombs a crime against humanity.

Life in Aleppo

The most urgent problems in Aleppo are power and water. When I arrived in late January there had been no electricity for 112 days (with the exception of a tantalising period when it had flickered on briefly for about half an hour a day).

The power station which used to supply the city’s population of more than two million is in the hands of Islamic State. The army is trying, so far without success, to recapture it. If not destroyed already, it certainly will be by the time IS fighters are driven out.

It is thought that last year the warring parties agreed to an energy-sharing deal that gave all the sides limited access to power but this seems to have collapsed because of the difficulty of reconciling all the divergent groups.

Aleppo’s second source of power used to be the national grid linking it through Hama to Damascus. Theoretically this could still operate, but once again only if the government and the numerous rebel groups were to cooperate. That seems out of the question. I asked for an interview with the director of electricity, but was told that he “had nothing to talk about”. No surprise, because this unfortunate man is one of the most unpopular men in Aleppo.

Meanwhile those Aleppans who can afford to do so employ private generators. In residential areas there is a chaotic mass of wires just above street level linking these generators to private apartments.

However, just two amps of electricity cost about 6,000 Syrian lira ($20) a month, in a country where incomes have collapsed and aid delivery is sporadic.

This is enough to power lighting, but not electrical appliances let alone central heating to mitigate Aleppo’s winter chill. Private homes are dank and for some reason seem even colder than the street outside.

The latest water problem was 12 days old when I reached the city. Once again the problem is Islamic State. Aleppo’s water supply comes from the Euphrates via a reservoir called "Assad’s lake" 90km to the north-east. There is a processing plant there, from which water is pumped via Nusra-controlled areas into the heart of the city.

Water has been cut off by the fighting before. This time all attempts to negotiate a solution with IS have failed. This tactic does not make IS any more popular and can be interpreted as a sign of desperation in the face of recent military setbacks - small consolation to Aleppans.

They have responded by digging wells. As with electricity, this adds hugely to the cost of living. Residents told me they pay 1,500 lira ($5) for 1,000 litres, enough to meet the basic needs of a family for about a week. To put this in perspective, water consumption in the US is about 340 litres per head every day. In Aleppo it is less than 20 litres per head.

Many people don’t have enough water to wash: doctors say there is an epidemic of fleas in the city.

These costs mount up. The salary of a state employee is about 30,000 Syrian lira a month ($100). Out of this he or she will spend 6,000 on water and a further 6,000 on electricity. But rents start at 15,000 a month for even the most squalid accommodation.

At Jamilla market in downtown Aleppo, I bought some pens and notepaper off Mahmood, a street vendor. He said that he and his extended family lived in a single room in a nearby apartment occupied by four different families, or about 25 people. How did he get by? “We’re alive,” he said.

Like the majority of people I met, newly married Mahmood was a refugee from a rebel-held area south of the city where he had had a good job in a jeans factory, now destroyed.

Aleppo University has set aside 17 out of its 20 dormitory blocks for refugees. This is bad luck for the students who are forced to sleep eight to a room intended for two as they try to continue their studies.

One man, a tailor before the war, shared a small room with his wife and seven children. He described how Free Syrian Army fighters burned down their house - leaving one daughter with terrible burns - after he refused to join them. He recalls that when they invaded his area of Aleppo province on 5 July, 2012 they “treated us like infidels. Made men grow long beards and women cover their faces”.

“This room here is better than a citadel in one of their places,” he added.

The family managed to escape but his cousins in the FSA continue to harass him even at the university. He said they tried to abduct one of his daughters, but neighbours intervened.

In a nearby room a man from a family of olive oil merchants told me that al-Nusra has murdered three of his brothers-in-law for alleged pro-government sympathies. One was beheaded, one was ripped to pieces after being tied between an electricity poll and a moving car. A fourth brother has been kidnapped and no one knows where he is.

Persecution of women and minorities

All the internally displaced Syrians in government-held Aleppo had the same story to tell about the areas they had fled: women covered and confined to the home; foreign fighters enforcing a reign of terror. They are sometimes unclear about which group they fled from.

The patchwork of alliances among rebels groups is extremely complex and constantly changing. There are US-approved groups as well as hardline Islamists factions. All oppose the Assad government, and will not work with Islamic State, but they are divided over tactics and ideology.

Human rights groups and the UN have levelled the worst accusations of war crimes at IS, Nusra and the government. However, all armed groups in Syria have been accused of gross human rights violations.

“I consider myself a Syrian,” said one refugee who did not want to give his name. “We have got all kinds of religion. We don’t believe in sectarian politics because that’s just a pretext they use to attack us.”

No wonder so many have fled. Aleppo (in common with the rest of Syria) has suffered a demographic catastrophe over the last 12 months. How many remain of the city’s once-flourishing population of two million plus? Everyone speaks of the multiple loss of friends who are now in exile.

Alaa al-Sayed, a civil rights campaigner who focuses on the protection of the city’s religious minority, estimates that there are just 5,000 Armenian Christians left, compared to a pre-war population of 60,000. There were 200,000 Christians - made up of ethnically Arab Christians and Christian Armenians – with the Christian community in the city drawing its roots to the early years after the death of Christ. Now Sayed estimates there are just 25,000.

On current trends the multi-confessional tolerance that has been a feature of life in Aleppo for two millennia will soon no longer exist.

The churches are encouraging worshippers to stay.

“One of our principles is that we shouldn’t leave the country when it is passing through difficult times,” said Reverend Selimian, pastor of the Armenian Evangelical Church. “When your mother gets sick do you get another mother? We as church leaders are staying here, we say there is no reason for you to go.”

Rev Selimian, a graduate of Chicago University, told me: “We distribute food, and pay for apartments rents. We pay for the electricity of more than 200 families. We provide medication free of charge.”

He added, however, that his churchgoers must ultimately make their own decisions. The poor make perilous journeys on makeshift boats across the sea from Turkey to Greece. The rich pay $7,000 for safe journeys across the same stretch of water on luxurious motor launches.

Many have no choice but to flee, and the last week has seen a fresh surge of refugees from the greater Aleppo area, reportedly caused by indiscriminate Russian bombing.

Refugee tales speak of Assad crimes

Determined to hear the other side of the story, after leaving the government-held areas of Aleppo I travelled to refugee camps in Jordan.

There I heard stories of mass slaughter by pro-government militias. I have met amputees whose life has been destroyed by barrel bombs, learnt of attacks by gangs carrying machetes, of mass rape as a weapon of war.

One sheep farmer from a south of Aleppo recalled the day (3 December, 2012) when the Syrian air force started bombing his village. He said they killed 1,500 people. He insisted there were no armed groups operating in the immediate vicinity. Now he lives in a makeshift camp in north Jordan.

A mother of eight children from a village near Hama in northern Syria told how she, her husband and eight children were driven out of her village by bombing.

“They slaughtered us, they dispossessed us, they destroyed everything we had. They entered into our homes,” she said.

She spoke of Iranian gangs with machetes looting and maiming: “I saw it with my own eyes. Either they chop off your right arm or your head.” There is no excusing or ignoring the crimes and barbarity of the Assad government and its allies.

Russian bombing in Deraa, the southern Syrian city where the revolt against the Assad government began in the spring of 2011, has caused a fresh wave of refugees to flee across the border into Jordan.

At a centre for amputees, I spoke to a young man who had lost his leg in a bombing raid. I asked him what he would do when he had recovered. There was no question in his mind. He would return to Deraa and fight, on a mission to take revenge for the killing of family members.

Tale of two cities

But the citizens of the government-held areas of Aleppo have another story to tell. They too say they are victims of terror and barbarism. They too have experienced immeasurable loss and intimidation. They believe they are fighting to save civilization.

I should state that I stayed exclusively in government-held areas. I made no attempt to cross the lines into rebel zones (I would have been kidnapped). Government minders accompanied me throughout the trip and were present at almost every conversation. But I am as certain as I can be that people told me the truth as they saw it. What follows is their story.

In the paragraphs that follow I will tell the story as I heard it from dozens of residents - schoolteachers, shopkeepers, imams, priests, businessmen, doctors, university professors, students and jobless refugees who have fled to government areas from the surrounding countryside.

When the Syrian uprising began in the early summer of 2011, Aleppo did not join. There were a handful of demonstrations but they were dealt with relatively gently. Some protestors were jailed but there was no armed response as took place in some other parts of Syria.

At the start of 2012, by which time much of Damascus was at war, the Aleppan business community says it was targeted in a series of assassinations and killings. Political and religious leaders say they were threatened with death or torture unless they went across to the rebels.

“We knew we were being targeted,” says Fares Shehabi, head of Aleppo’s chamber of industry. “We knew what was coming. We sent a message for the army to be sent to Aleppo.” The request was ignored.

On 5 July of that year an armed convoy - the Brigade of Tawheed, an Islamist group that has previously praised Nusra - rolled into ancient Aleppo. It dispersed, burnt down police stations, set up road blocks.

Within a few weeks, the rebel brigades had taken over most of the city. “At first we thought they were Syrians,” said Shehabi. “But after a few weeks we got reports about foreigners. Fighters from Chechnya, Uzbekistan, Jordan, Saudi, Iraq, Eqypt.”

“This was not regime change, it was invasion. And why was it taking a religious theme? Why does it have a beard? We are not ready to replace a secular society with a religious one.”

The newcomers established religious courts. Women were confined to their home and made to cover up. Alcohol and smoking were banned. “I’m a Sunni, yet they consider me an infidel,” Shehabi said.

The Aleppo businessman argues that the paradigm of the Syrian conflict favoured by Western governments and media is false.

UK Prime Minister David Cameron and his ministers have repeatedly portrayed the war as a murderous war waged by a fanatical minority loyal to President Assad against the overwhelming majority of the Syrian people.

Since the president belongs to the minority Alawite interpretation of Islam, this implies that the war is a sectarian conflict between supporters of the Alawite sect and the mass of Sunni Muslims.

Shehabi challenges this. He argues that the real divide is between a culture of religious tolerance - including moderate Sunnis like him - and the Wahhabi interpretation of Islam sponsored by Saudi Arabia.

“This is not a war about President Assad and his regime or state. I am not a member of the Baath Party. This is about identity and lifestyle,” he said.

For Shehabi and every other Aleppo resident I met, the war should be understood in a radically different way. They stress that in Aleppo there is a culture of tolerance and understanding embracing Christians, Shia, Alawites and ordinary Sunnis – an intermingling which has existed since time immemorial.

Again and again, residents asked me why the British government and NATO were on the side of militant Islam and terrorism.

“Go to Idlib today,” says Shehabi about the northeastern city seized with the help of the Western-sponsored Free Syrian forces last year. “It is like Kandahar [in Afghanistan]. How can you claim that you want to make Syria a democracy if you impose religious courts which do not recognise our religions or our ethnic variety.”

Shehabi further asserts that what he believes that the insurgency in Aleppo was not part of a Syrian uprising but was instead deliberately supplied and orchestrated from Turkey.

“The Turks gave them weapons,” he said. “They allowed the fighters across the border. They nursed the wounded in their hospitals.”

He claims that Turkey was motivated by economic gain, deliberately setting out to destroy Aleppo which it sees as an economic rival. Shehabi says that he has cast-iron evidence that Turkish-backed fighters systematically stripped the production lines in Aleppo’s industrial centre and shipped the machinery back across the border.

He complained publicly about the stripping of Aleppo’s factories shortly after the attacks began and, in his capacity as head of the Aleppo chamber of Industry, issued writs against Turkish President Erdogan for damages. He says that two weeks later the grand offices of the chamber were completely destroyed in a massive bomb attack.

The demolition of Aleppo’s industrial infrastructure is only one part of the story. Before the revolution it was a sophisticated city. There was a system of free public health that offered a broad range of treatment from daily diseases to more complex problems like cancers.

I met Dr Mahamad al-Hazouri, head of the department of health, in his office at Aleppo’s Razi Hospital.

“In July 2012,” he told me, “terrorism hit at the infrastructure of our health centres. They put six out of our 16 hospitals out of service as well as 100 out of 201 primary health centres and 12 out of 14 comprehensive centres. They also wiped out the ambulance service.”

He gave the example of Aleppo’s eye hospital: “It had been one of the great hospitals in the north of Syria, and was turned by rebels into a jail for detainees.”

Hazouri and his colleagues described their efforts to continue to provide a comprehensive service to the general population. Staff make heroic trips to rebel areas as part of their vaccination programme: “They get humiliated. Insurgents say that they are infidel. They refuse to let us in.”

As a result diseases that have long been forgotten are making a return. Hazouri said that polio was eradicated from Syria more than 10 years ago: there are now cases in Islamic State-occupied areas. Meanwhile there is a chronic shortage of drugs and medical equipment.

The school system has suffered comparable devastation. Ibrahim Maso, head of the education directorate, told me how his department had supervised 4,400 schools before the war, with 1.5 million students in the greater Aleppo area.

Some 3,000 of those schools are now under rebel control. “Only 915 schools are now teaching the government curriculum,” said Maso, who was an Arabic teacher for 17 years and school principal for a decade. He continues to pay the salaries of teachers stranded in the rebel areas, even when they are prevented from teaching.

I met one such teacher, who had travelled from her Islamic State-held village to the east of Aleppo in order to collect her 30,000 lira ($100) monthly salary.

Before the war, the journey would have taken less than an hour. Instead, she had to spend five days traversing Islamic State and al-Nusra checkpoints to get to the education department. She was still wearing the black robes which the Islamic State enforces: IS confine all women to their home unless completely covered in black with not a centimetre of flesh showing. She told how she had heard British and French accents among the IS fighters and well as “very blond Americans and black ones, speaking classical Arabic”.

Often these fighters drive round the streets in Toyota pick-up trucks ordering people out of their houses to “come and see the punishment” - usually a beheading or crucifixion.

“Everything behind the curtain is allowed. Sex, smoking and wine. Some women from our town go into their houses alone,” she said.

She described how they knock on doors asking permission to marry the daughters of the town. One man who refused was beheaded.

The schools have been closed, but IS enforces its own education system: “The teenagers are taken to mosques for religious teaching. They brainwash the young men. They are told to attack their parents.”

Yet this brave and stoical teacher told me that she was not afraid because she was sustained by her Islamic faith: “When you are with God you fear no one.”

She was preparing to make the journey back to rejoin her husband and children, and spoke of her fears for the future.

The Syrian army is approaching her town as it regains ground from Islamic State across eastern Aleppo: “The fighters are preparing ambushes with explosives. They are moving their wives and families out. They are keeping us as human shields for them.”

The heroism of some of the people I met is beyond computation.

One headmaster told me how he has tried to keep his school open in an Islamic State area. He was held in solitary confinement for 30 days in a cell with no toilet. Occasionally, he was beaten with an electric cable. Once a box full of scorpions was put into his cell. He was told that “this was the fate of every Shahiba [government worker]. You will be an example to everyone who works for the government.”

Aleppo traces its history back 7,000 years and is one of the oldest constantly inhabited cities in the world. During that time, it has endured countless catastrophes. It was sacked twice by the Mongols and once by Central Asian emperor Timur at the start of the 15th century. It has been destroyed by earthquake.

The events of the Syrian civil war are comparable in scale and horror to those past catastrophes. Of course, peace will be restored at some point and the city rebuilt. During the time I spent in Aleppo, the Syrian army was cutting off the routes between the Turkish border and the city. This means that supply lines from Turkey to al-Nusra and Islamic State were no longer functioning. Slowly - as in Stalingrad in 1942 - the besiegers are turning into the besieged.

Edward Dark, an Aleppo-based contributor for Middle East Eye, tweeted out on last week: “This is the beginning of the end of jihadi presence in Aleppo. After four years of war and terror, people can finally see the end in sight.”

There was still stalemate in Aleppo city itself as I drove out of the city, but in the countryside around events are moving very fast.

- Peter Oborne was British Press Awards Columnist of the Year 2013. He recently resigned as chief political columnist of the Daily Telegraph. His books include The Triumph of the Political Class; The Rise of Political Lying;and Why the West is Wrong about Nuclear Iran.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo Credit: Syrian army soldiers walk through government-held Aleppo in 2015 (AFP)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].