Saudi war for Yemen oil pipeline is empowering al-Qaeda, IS

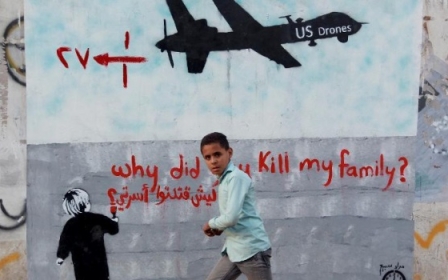

Nearly 3,000 civilians have been slaughtered and a million displaced in Saudi Arabia’s noble aerial bombardment of Yemen, which is backed by the United States and Britain.

Over 14 million Yemenis face food insecurity – a jump of 12 percent since June 2015. Out of these, three million children are malnourished. And across the country, an estimated 20 million people cannot safely access clean water.

The Saudi air force has systematically bombed Yemen’s civilian infrastructure in flagrant violation of international humanitarian law. An official UN report to the Security Council leaked last month found that the Saudis have “conducted airstrikes targeting civilians and civilian objects … including camps for internally displaced persons and refugees; civilian gatherings, including weddings; civilian vehicles, including buses; civilian residential areas; medical facilities; schools; mosques; markets, factories and food storage warehouses; and other essential civilian infrastructure, such as the airport in Sanaa, the port in Hudaida and domestic transit routes.”

US-made cluster bombs have been dropped on residential areas – an act that even the UN Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon tepidly concedes “may amount to a war crime”.

In other words, Saudi Arabia is a rogue state. But make no mistake. This kingdom is our rogue state.

The US and British governments supplying Saudi Arabia with weapons to be unleashed on Yemeni civilians pretend they are not involved in the war, not responsible for the war crimes of our rogue state ally.

A UK Ministry of Defence spokesperson insisted that British forces were merely advising “on best practice targeting techniques … UK military personnel are not directly involved in Saudi-led coalition operations.”

But these are weasel words, given the recent revelation from the Saudi foreign minister, Adel al-Jubeir, that British and American military officials are working “in the command and control centre for Saudi airstrikes on Yemen.”

Presumably taxpayers are not paying them to stand around drinking tea all day.

No – we’re paying them to supervise the air war. According to the Saudi foreign minister: “We have British officials and American officials and officials from other countries in our command and control centre. They know what the target list is and they have a sense of what it is that we are doing and what we are not doing.”

US and UK officials have “been able to scrutinise its air campaign, and were satisfied by its safeguards”.

Back in April 2015, US officials were far more candid about this arrangement. US Deputy Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken told a press conference in Riyadh that the US had increased its intelligence sharing with the Saudis via a “joint coordination planning cell,” involving target selection.

Whatever the case, the civilised leaders of the free world have an insiders’ birds-eye view of the Saudi military’s systemic war crimes in Yemen – and it appears they approve.

Sectarian war?

The goals of the Saudi-led coalition are obscure.

It’s widely recognised that the war has broad geopolitical, sectarian dynamics. The Saudis fear that the rise of the Houthis signals the growing influence of Iran in Yemen.

With Iran active in Syria, Iraq, and Lebanon, Saudi Arabia sees the Houthi rebellion as yet another component in its strategic encirclement by Iranian proxy forces. This is compounded by the US-backed Iran nuclear deal, which paves the way for Iran’s integration into global markets, the opening up of its underdeveloped oil and gas sectors, and its consolidation as a regional power.

But this narrative is not the whole story. While Iran’s contacts with the Houthis are beyond question, before Saudi’s air campaign, the Houthis had acquired most of their weapons from two sources: the black market and ex-President Ali Abdullah Saleh.

US intelligence officials confirm that Iran had explicitly warned the Houthis not to attack Yemen’s capital last year. “It remains our assessment that Iran does not exert command and control over the Houthis in Yemen,” said Bernadette Meehan, a spokeswoman for the White House National Security Council.

According to former UN special envoy to Yemen, Jamal Benomar, the Saudi airstrikes scuppered an imminent peace deal that would have led to a power-sharing arrangement between 12 rival political and tribal groups.

“When this campaign started, one thing that was significant but went unnoticed is that the Yemenis were close to a deal that would institute power-sharing with all sides, including the Houthis,” Benomar told the Wall Street Journal.

This was not, then, about Iran. The Saudis, and apparently the US and UK, did not want to see a genuine transition to the semblance of a democratic Yemen.

In fact, the US is explicitly opposed to the democratisation of the entire Gulf region, hell-bent on ‘stabilising’ the flow of Gulf oil to global markets.

In March 2015, US military and NATO consultant Anthony Cordesman of the Washington, DC-based Center for Strategic and International Studies explained that: “Yemen is of major strategic importance to the United States, as is the broader stability of Saudi Arabia all of the Arab Gulf states. For all of the talk of US energy ‘independence,’ the reality remains very different. The increase in petroleum and alternative fuels outside the Gulf has not changed its vital strategic importance to the global and US economy … Yemen does not match the strategic importance of the Gulf, but it is still of great strategic importance to the stability of Saudi Arabia and the Arabian Peninsula.”

In other words, the war on Yemen is about protecting the West’s principal Gulf rogue state, to keep the oil flowing. Cordesman goes on to note: “Yemen’s territory and islands play a critical role in the security of another global chokepoint at the southeastern end of the Red Sea called the Bab el-Mandab or ‘gate of tears’.”

The Bab el-Mandeb Strait is “a chokepoint between the Horn of Africa and the Middle East, and it is a strategic link between the Mediterranean Sea and the Indian Ocean,” carrying most exports from the Persian Gulf that transit the Suez Canal and Suez-Mediterranean (SUMED) pipeline.

“Any hostile air or sea presence in Yemen could threaten the entire traffic through the Suez Canal,” adds Cordesman, “as well as a daily flow of oil and petroleum products that the EIA [US Energy Information Administration] estimates increased from 2.9 mmb/d [million barrels per day] in 2009 to 3.8 mmb/d in 2013".

The Yemen pipeline dream

But there’s a parallel sub-goal here, acknowledged in private by Western officials, but not discussed in public: Yemen has as yet untapped potential to provide an alternative set of oil and gas trans-shipment routes for the export of Saudi oil, bypassing Iran and the Strait of Hormuz.

The reality of the kingdom’s ambitions in this regard are laid bare in a secret 2008 State Department cable obtained by Wikileaks, from the US embassy in Yemen to the Secretary of State:

“A British diplomat based in Yemen told PolOff [US embassy political officer] that Saudi Arabia had an interest to build a pipeline, wholly owned, operated and protected by Saudi Arabia, through Hadramawt to a port on the Gulf of Aden, thereby bypassing the Arabian Gulf/Persian Gulf and the straits of Hormuz.

"Saleh has always opposed this. The diplomat contended that Saudi Arabia, through supporting Yemeni military leadership, paying for the loyalty of sheikhs and other means, was positioning itself to ensure it would, for the right price, obtain the rights for this pipeline from Saleh’s successor.”

Indeed, Yemen’s eastern governorate of Hadramaut has remained curiously free from Saudi bombardment. The province, Yemen’s largest, contains the bulk of Yemen’s remaining oil and gas resources.

“The kingdom’s primary interest in the governorate is the possible construction of an oil pipeline. Such a pipeline has long been a dream of the government of Saudi Arabia,” observes Michael Horton, a senior analyst on Yemen at the Jamestown Foundation. “A pipeline through the Hadramawt would give Saudi Arabia and its Gulf State allies direct access to the Gulf of Aden and the Indian Ocean; it would allow them to bypass the Strait of Hormuz, a strategic chokepoint that could be, at least temporarily, blocked by Iran in a future conflict. The prospect of securing a route for a future pipeline through the Hadramawt likely figures in Saudi Arabia’s broader long-term strategy in Yemen.”

Hiding the pipeline connection

Western officials are keen to avoid public consciousness of the energy geopolitics behind the escalating conflict.

Last year, a cutting analysis of these issues was posted on a personal blog on 2 June 2015 by Joke Buringa, a senior advisor on security and rule of law in Yemen at the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

“Fear of an Iranian blockade of the Hormuz Strait, and the possibly disastrous results for the global economy, has existed for years,” she wrote in the article, titled "Divide and Rule: Saudi Arabia, Oil and Yemen." “The US therefore pressured the Gulf States to develop alternatives. In 2007 Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, the UAE, Oman and Yemen jointly launched the Trans-Arabia Oil Pipeline project. New pipelines were to be constructed from the Saudi Ras Tannurah on the Persian Gulf and the UAE to the Gulf of Oman (one to the Emirate of Fujairah and two lines to Oman) and the Gulf of Aden (two lines to Yemen).”

In 2012, the connection between Abu Dhabi and Fujairah, within the UAE, became operational. Meanwhile, Iran and Oman moved to sign their own pipeline deal. “Distrust about the intentions of Oman increased the attractiveness of the Hadramawt option in Yemen, a longstanding wish of Saudi Arabia,” wrote Buringa.

President Saleh, however, was a major obstacle to Saudi ambitions. According to Buringa, he “opposed the construction of a pipeline under Saudi control over Yemeni territory. For many years the Saudis invested in tribal leaders in the hope to execute this project under Saleh’s successor. The 2011 popular uprisings by demonstrators calling for democracy upset these plans.”

Buringa is the only senior Western government official to have acknowledged this matter publicly. But when I contacted her to request an interview on 1 February, four days later I received a response from Roel van der Meij, a spokesperson for corporate affairs at the Dutch government’s foreign ministry: “Mrs. Joke Buringa asked me to inform you that she is not available for the interview.”

Buringa’s entire blog – previously available at www.jokeburinga.com – had in the meantime been completely removed.

An archived version of her article on the energy geopolitics of the Saudi war in Yemen is available at the Wayback Machine.

I asked both Buringa and van der Meij why Buringa’s blog had been completely deleted so quickly after I had sent my request for an interview, and whether she had been forced to do so under government pressure to protect Dutch ties with Saudi Arabia.

In an email, Buringa denied that she was pressured by the Dutch foreign ministry to delete the blog: “Sorry to disappoint you, but I was not pressured by the ministry. The layout of the blog had bothered me from the beginning and I had been meaning to change it for months … Your question reminded me that I wanted to change my site and rethink what I want to do with it. Don't read more into it.”

However, the Dutch government corporate affairs spokesperson, van der Meij, did not respond to multiple email and telephone requests for comment regarding the removal of the blog.

Many Dutch firms are active in the kingdom running joint investments, including the Anglo-Dutch oil major Shell. Due to the Netherlands’ position as a gateway to Europe, two Saudi Arabian multinationals – the national oil firm Aramco and the petrochemicals giant SABIC – have their European headquarters in The Hague and Sittard, both in the Netherlands. Dutch exports to Saudi Arabia have also increased dramatically in recent years, rising 25 percent between 2006 and 2010.

In 2013, Saudi Arabia exported just under 34 billion euros ($38.5bn) of mineral fuels to the Netherlands, and imported from the Dutch just over 8 billion euros ($9bn) of machines and transport material, 4.8 billion euros ($5.4bn) of chemical products, and 3.7 billion euros ($4.2bn) of foodstuffs and animals.

The Saudi alliance with al-Qaeda

Among the prime beneficiaries of the Saudi strategy in Yemen is al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), the same group that took responsibility for the Charlie Hebdo slaughter in Paris.

“The governorate of Hadramawt is one of the few areas where the Saudi-led coalition did not conduct any air strikes,” noted Buringa. “The port and the international airport of al-Mukalla are in optimal shape and under the control of al-Qaeda. Moreover, Saudi Arabia has been delivering arms to al-Qaeda, (which) is expanding its sphere of influence.”

The Saudi alliance with al-Qaeda-affiliated terrorists in Yemen was brought to light last June when the Saudi-backed "transitional" government of Abd Rubbuh Mansour Hadi dispatched a representative to Geneva as an official delegate for UN talks.

It turned out that the representative was none other than Abdulwahab Humayqani, identified as a "specifically designated global terrorist" in 2013 by the US Treasury for recruiting and financing for AQAP. Humayqani was also allegedly behind an al-Qaeda car bombing that killed seven at a Yemeni Republican Guard base in 2012.

Other analysts concur. As Michael Horton comments in the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor: “AQAP may also benefit from the fact that it could well be regarded as a useful proxy by Saudi Arabia in its war against the Houthis. Saudi Arabia and its allies are arming a host of disparate militias across southern Yemen. It is almost certain that some, if not much, of the funding and materiel will make its way to AQAP and quite possibly the Islamic State.”

While trumpeting the war on IS in Iraq and Syria, the West is paving the way for the resurgence of both al-Qaeda and IS in Yemen.

“Saudi Arabia does not want a strong, democratic country on the other side of the more than 1,500 kilometre-long border that separates both countries [Saudi Arabia and Yemen],” Dutch foreign ministry official Joke Buringa had remarked in her now-censored article. Neither, it seems, do the US and UK. She added: “Those pipelines to Mukalla will probably get there eventually.”

They probably won’t – but there’ll still be blowback.

- Nafeez Ahmed PhD is an investigative journalist, international security scholar and bestselling author who tracks what he calls the 'crisis of civilization.' He is a winner of the Project Censored Award for Outstanding Investigative Journalism for his Guardian reporting on the intersection of global ecological, energy and economic crises with regional geopolitics and conflicts. He has also written for The Independent, Sydney Morning Herald, The Age, The Scotsman, Foreign Policy, The Atlantic, Quartz, Prospect, New Statesman, Le Monde diplomatique, New Internationalist. His work on the root causes and covert operations linked to international terrorism officially contributed to the 9/11 Commission and the 7/7 Coroner’s Inquest.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: A Yemeni man poses with a national flag at a sports hall that was partially destroyed by Saudi-led air strikes in the Yemeni capital Sanaa on 19 January, 2016 (AFP).

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].