The case for cultural boycott of Israel

The case for a boycott of Israel is straightforward, based on: the reality of Israel’s policies of colonialism and apartheid; the Palestinians’ appeal for solidarity, including the 2005 call for a global Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) campaign; and the effectiveness of BDS as a tactic.

But what about a cultural boycott? This is a problem for some people who agree with the above argument – yet it is also based on a similar, logical argument.

First, it is part of the broader case for BDS, as outlined above – though with some particular angles of its own. For example, Israeli settler-colonialism has always included attacks on Palestinian culture, from the looting of libraries during the ethnic cleansing of 1948, through to the violent attacks by Israeli authorities on Palestinian cultural events in Occupied East Jerusalem.

In addition, there is a specific cultural boycott call from Palestinians: the Palestinian Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel (PACBI) urges cultural workers worldwide to “comprehensively and consistently boycott all Israeli academic and cultural institutions as a contribution to the struggle to end Israel’s occupation, colonisation and system of apartheid.”

Second, the boycott is a response to the complicity of Israel’s cultural institutions in Israel’s crimes. The PACBI-developed guidelines are quite clear in this respect, that as far as the BDS movement is concerned, it is an “institutional boycott” that is being called for.

Habima Theatre, for example, performs in West Bank settlements, whose very existence is part of an inherently discriminatory, apartheid system. The Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, meanwhile, is proud to perform “special concerts for IDF soldiers at their outposts”.

Third, Israel has chosen to mobilise culture as a means of international propaganda, to create a brand for the state that masks policies slammed by United Nations agencies and numerous human rights groups as constituting systematic discrimination, segregation and forced displacement.

In 2005, Israeli newspaper Ha’aretz revealed plans by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to adopt “a new means of presenting Israel to the world”.

The shift meant giving Israeli diplomats abroad the ability to decide “when and how often the State of Israel will represent itself through a booklet explaining the need for the separation fence, and when and how often it will do so through, say, a play.”

A senior ministry official at the time commented: “We are seeing culture as a hasbara tool of the first rank, and I do not differentiate between hasbara and culture.” Hasbara, literally "explanation", is “a form of propaganda aimed at an international audience”.

In 2008, the Israeli government hired a British PR firm “to create a brand disconnected from the Arab-Israeli conflict that focuses instead on Israel’s scientific and cultural achievements.” Post-Operation Cast Lead, in 2009, an official declared:

We will send well-known novelists and writers overseas, theatre companies, exhibits. This way, you show Israel’s prettier face, so we are not thought of purely in the context of war.

An individual who – ironically and unwittingly – perhaps best makes the case for a cultural boycott is Idan Raichel, the well-known Israeli singer-songwriter and musician who on 23 February, will be performing at London’s Barbican Centre.

Internationally, Raichel is portrayed almost as a saint. The Boston Globe has hailed his work as “a fascinating window into the young, tolerant, multi-ethnic Israel taking shape away from the headlines”, describing him as “a humanist and compulsive intercultural collaborator”.

“Israel’s most ubiquitous export since drip irrigation,” in the words of The Jerusalem Post, Raichel’s music is lauded as “a multi-ethnic tour de force” and a celebration of “diversity and coexistence.”

Raichel’s track record, however, is something quite different. In 2007, for example, he performed at the 40th-anniversary celebration of Gush Etzion, a cluster of illegal settlements in the southern West Bank that restrict Palestinians’ access to agricultural and cultural resources.

His appearance at the event was denounced by Israeli anti-occupation activists, but Raichel was unmoved; in a BBC interview in 2010 he justified the decision.

Raichel has praised the military as a “basic ingredient” of Israeli society, and given his support for a "Thank Israeli Soldiers" initiative. More disturbingly still, in late 2013 Raichel used his Instagram account to come out in defence of a former Israeli army interrogator accused of torture.

Raichel is a willing recruit in Israeli government propaganda efforts, stating in a 2008 interview: “We certainly see ourselves as ambassadors of Israel in the world, cultural ambassadors, hasbara ambassadors, also in regards to the political conflict.” In 2012, he told an Israeli newspaper: “I believe our role as artists [is] to enlist in Israeli hasbara.”

In 2005, Raichel toured North American campuses, according to Ha’aretz, thanks to “financial support” from Israel’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs as part of its "Israel beyond the conflict" scheme. More recently, Raichel has been sent to local schools by Israel’s embassy in Washington DC.

In 2006, he met with American journalists as part of a propaganda junket organised by the Israeli government and advocacy groups, a trip that reflected “an out-of-box approach” to “hasbara”.

Raichel has, in other words, become “an ambassador without portfolio”, and his music a form of “soft-diplomacy”. In 2012, a former Israeli consulate official in the US praised The Idan Raichel Project as “one of Israel’s most effective ambassadors”, adding: “The Hasbara value is priceless”.

The Times has described Idan Raichel as a “one-man Middle East peace accord”. Through the disparity between his image and his politics, and his willing participation in government rebranding efforts, Raichel is in fact a one-man argument for cultural boycott.

- Ben White is the author of "Israeli Apartheid: A Beginner’s Guide’ and ‘Palestinians in Israel: Segregation, Discrimination and Democracy". He is a writer for Middle East Monitor, and his articles have been published by Al Jazeera, al-Araby, Huffington Post, The Electronic Intifada, The Guardian’s Comment is free, and more.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

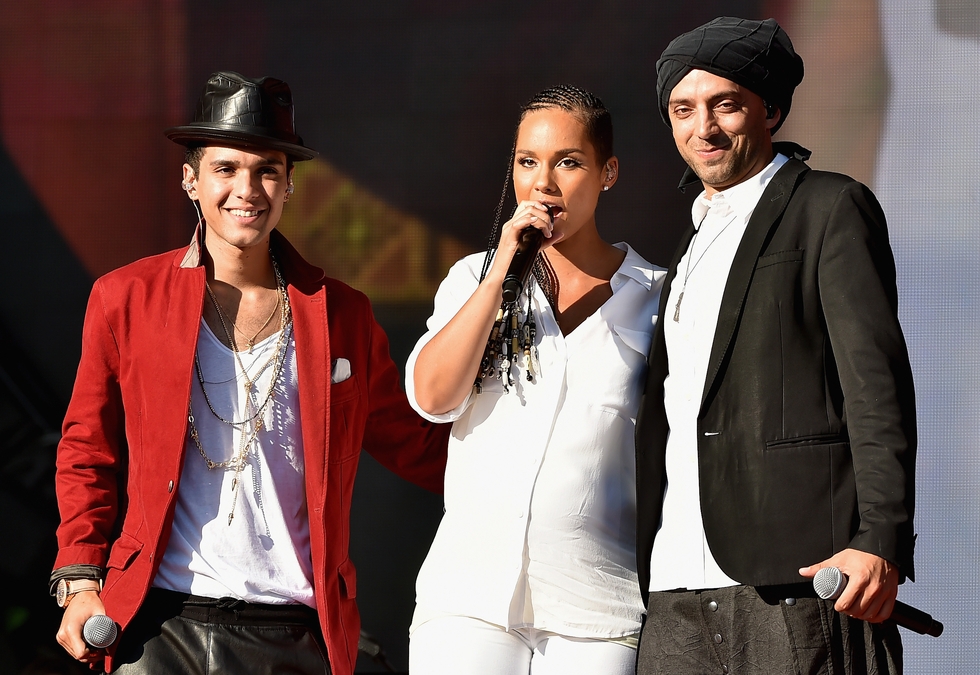

Photo: (L-R) Amir-Kanoon, Alicia Keys and Idan Raichel perform onstage at the 2014 Global Citizen Festival to end extreme poverty by 2030 in Central Park on 27 September, 2014 in New York City (Theo Wargo/Getty Images for Global Citizen Festival/AFP).

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].