My father, Eric Avebury, the patron saint of unpopular human rights causes

Eric Avebury was a contradiction in a number of respects. The unexpected inheritor of an aristocratic title granted to his grandfather 70 years before, he was fundamentally opposed to hereditary power and voted to abolish it, yet was re-elected by his party when most of the hereditary Lords were kicked out in 1999.

He was incurably old-fashioned in many ways, disliking parties, small talk and strong displays of emotion, yet he became more liberal as he got older, to the point where he repeatedly voted against his own party on issues like the Bedroom Tax.

A committed secularist and atheist, he was still moved deeply by the religious music of Bach, and became a Buddhist, a system of belief which he took more as an ethical framework than a religion. He had no hobbies besides music; helping people was his hobby, and he did it as a job that he could never quit. From morning until midnight, he would be at his desk, writing letter after letter to ministers, refugees, prisoners, colleagues and organisations.

People from communities who had never been listened to were surprised that this member of the establishment was paying attention to them and offered to let them come and speak at meetings in Parliament. He gave resistance movements hope and made activists and revolutionaries feel that their struggles were not in vain.

In the causes he championed, he never limited himself to a handful of specialities. His office at home is stacked with boxes and files corresponding to all the different subjects he tackled. He tried to help find a resolution to the Chittagong Hill Tracts conflict in Bangladesh, to make caste discrimination illegal in the UK, to raise attention to the genocide of the Hazara community in Pakistan, as well as the persecution of Ahmadi Muslims, the Baha’i, the Kurds in Iraq and Turkey (for which he was banned from Turkey from 1995-2005); he campaigned for the recognition of the Armenian Genocide, the state of Somaliland, for the rights of Chagos Islanders, for Gypsies and Travellers and Marriage Equality in the UK, Kashmiris, Dalits in India, West Papuans… the list goes on.

This was not an approach that should have made him friends, but it did. Not that there weren’t enemies. He was once sued for libel by Winston Churchill’s grandson after he called him a racist. An Egyptian newspaper called him a terrorist and a drug smuggler (he sued them for libel) and in the late 90s, he was called a "terrorist godfather" by a publication of crackpot US cult leader Lyndon LaRouche.

The Times’ obituary of Eric said he was a supporter of the "Iranian-backed" Bahraini opposition. This despite the Bahraini government’s own report finding no evidence of any Iranian involvement in Bahrain. Incidentally, Eric was also a strong supporter of the National Council of Resistance of Iran, the main international opposition movement to the Islamic Republic’s theocratic government.

If you stick up for people, it seems, there will always be someone who wants to accuse you of doing it for some secret, terrorist purpose. Some people are so cynical they can’t believe anybody would honestly help the oppressed for no personal gain. But that was Eric - he was the opposite of a cynic; he never gave up believing that humanity could be better, despite immersing himself in its worst failings.

My father started working on human rights in Bahrain in the early 90s, long before most politicians or international media paid it any attention at all. By that point, activists in the country had already been calling for democratic reforms since the 1950s, and it is striking that so little has changed in Bahrain in terms of the rights which citizens enjoy since then.

Eric had done a lot of work in the Middle East prior to the 90s, visiting the Shatila and Sabra refugee camps in Lebanon in 1980 and pressing Arafat’s PLO to renounce violence. In the 80s and 90s he visited Massoud Barzani and Jalal Talibani in Kurdish Iraq and attempted to reconcile the rivals (he found Talibani erudite and friendly, Barzani much less so). He also met Abdullah Ocalan in Damascus, trying to persuade the PKK to take part in the Turkish political process as Sinn Fein had eventually done in Northern Ireland.

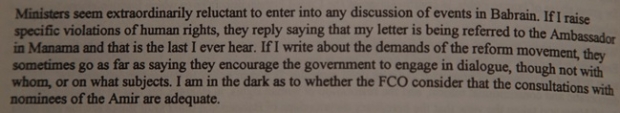

Throughout the 90s, my father wrote letter after letter to the British government, asking them to raise concerns with the Bahraini government and press them to release political prisoners. His letters from December 1994 to June 1996 were collected in a publication of the Parliamentary Human Rights Group called Bahrain: A Brickwall. Here’s a representative sample from December 1995:

Nothing has changed since then. In 1999, the Emir died and his son Hamad al-Khalifa took over, promising to be a reformer. The main demand of the opposition then, as now, was to have a constitution that guaranteed meaningful freedom of speech, association, and political representation. Sadly, that is not what the British or American governments want for Bahrain. They want it to be an economically stable place which supports Western interests, and if that means repressing the legitimate demands of the Bahraini people, then that is just a mild embarrassment to their professed interest in promoting human rights.

Hamad proposed a new constitution in 2001 which was approved by 98.4 percent of Bahrainis. Then, with the sleight of hand of a magician, the constitution people had voted on was replaced by a new one which marginalised the elected part of the legislature, allowing the unelected rulers to retain their power. My father was in Bahrain around this time, and later told me that he had been sitting in a majlis with Hamad as part of his attempts to engage with the government. He told Hamad that creating a truly democratic system would not be easy and required more than superficial reforms. Hamad nodded in agreement, but my father was not convinced of his sincerity.

After the 2011 uprising, Bahrain’s rulers hardened their resolve to not give in to any of the reformers’ demands. Most of the dissidents who returned to Bahrain in 2002 under a general amnesty were re-arrested and thrown in jail for life, such as Abdulhadi Alkhawaja. Anyone who was involved in the uprising is now either in exile or in jail. My father was a patient man. He knew it took decades for justice to be done, but with Bahrain, he saw a regime that didn’t want to change, and a British government that had no interest in making them do so.

That is why he backed the pro-democracy movement so strongly: because nobody else was going to. The truth is that we may never see reform come to Bahrain, at least until the Gulf autocracies are forced to when their oil runs dry. But that does not mean that anyone fighting to make Bahrain a better society is going to give up, just because it’s hard.

The road to freedom is long and hard, and on the way you’re sometimes lucky enough to have a guide who helps you carry your burden and show you the way. Eric’s example will inspire many people who were following him to pick up the torch he carried, and wherever their torches illuminate injustice for the world to see, my father will be there in spirit.

John Lubbock is a journalist and filmmaker who has recently completed the film "100 Years Later". He is a graduate of International Politics MA at City University London.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: Eric Avebury in his office, 2013 (John Lubbock).

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].