Yemeni photographers fight despair and trauma of war

It is nearly one year since the Saudi-led coalition began their bombing campaign in Yemen and Yemenis are constantly trying to find new ways to express their feelings about the tragedy unfolding in their country.

For Yemeni photographers who had to leave their homeland, they are not only turning to their photographic craft to cope with the pain of longing and separation from their families and loved ones, but they are also creating alternative narratives about the reality of what it now means to be Yemeni. A narrative that goes beyond the headlines and one which tells the stories of the people on the ground and those forced into the diaspora.

This relationship between the war and displaced Yemeni photographers was the topic explored at a two-day workshop in Jordan last month run by the Yemeni Salon Organisation. Founded in 2012 by myself and my colleague Hana al-Khamri, the Yemeni Salon organisation is a diaspora group focusing on cultural and media empowerment projects about Yemen.

As a Yemeni who has been in self-exile in Sweden for the past five years, I prepared myself for the discomfort of seeing how the diaspora is expanding – a sign of how tragic the situation in Yemen is – and how we are finding ourselves in a position where we must be the voice of our people. I knew the workshop would be emotionally exhausting as it addressed heartbreaking stories about the conflict and subsequent displacement.

The work of the photographers certainly presented a very different view of the situation in Yemen compared to the narrative presented in mainstream media.

Despite being scattered around the world, the photographers' work showed how the war impacted each of them - and revealed their resilience. Among the five Yemeni photographers exhibited, two of them - Abdulrahman Jaber and Yasmin Al-Nadheri - had a particularly deep impact on me; so let me present their work.

My father’s last days

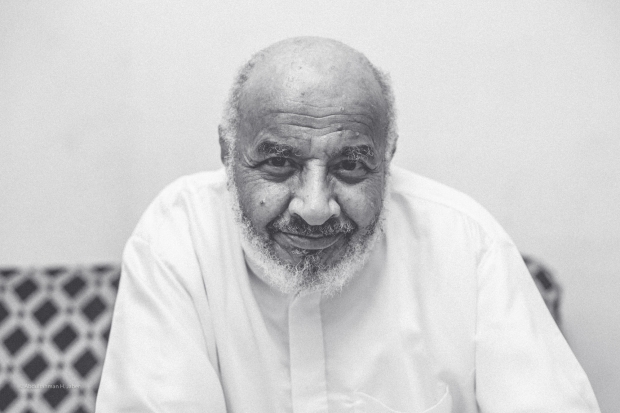

When Yemeni photographer and designer Abdulrahman Jaber decided to leave Yemen after the war broke out last year, little did he know that he was about to face the most difficult experience of his life: the death of his father while he was abroad. His passion for photography was to play an important role in how he fought the agony of the deeply felt loss.

Jaber’s interest in photography goes back to before the war. “I’m a designer who’s a shy photographer,” said Jaber. His modesty is admirable, given that his photography and design work in Yemen have been receiving great attention since 2005. Jaber's particular brand of photograph is usually characterised by its stylishness and simplicity.

When the revolution erupted in 2011, Jaber was one of the first local photographers who rushed to Change Square in Yemen's capital Sanaa. It would be rare to see him without his camera, since so much of his time was taken up capturing inspiring moments from the epicentre of the revolution.

Following the armed clashes in Sanaa at the end of 2011, Jaber was inspired to showcase how the people of the city were attempting to forget about the seemingly constant hail of bullets and the sound of gunfire, and to just go on with their lives.

"I was struck by how it was becoming the norm that you would be at a wedding with loud celebratory music being played and dancing people swirling around while you could hear the sound of gunfire echoing just outside as different groups were clashing. The people at the wedding weren’t panicking nor would they stop the wedding party,” explains Jaber, they just carried on.

That is how his series of photographs titled Situation was born, depicting the strong desire of the people to continue their normal lives, despite what was going on around them.

As the war raged around him, in March 2015, Jaber turned his camera to his private life and made the brave and candid decision to document and share one of the most poignant events in his life - the death of his father.

“Due to the deteriorating security situation and the worsening health care services, it was extremely difficult to obtain the crucial medical assistance for my father, especially when he needed it the most,” says Jaber.

In the course of Jaber’s father being medicated at home and increasing numbers of visits to the hospital, Jaber made the decision to document his father’s last days. Jaber explains: “I created a journal of photographs of him while I was in Sanaa and when I left to go to Turkey, my brother, Suhaib, continued taking the photos. It was just a few weeks after I left that I received the devastating news that my father had passed away.

"I had to share the photographs. I called the collection of his final images My Father’s Last Day. While the pictures certainly say volumes about the harsh reality of life in Yemen, I think sharing these pictures is a way to celebrate the memory of my beloved father too.”

The truthfulness and sincerity in this series are so strong because it also mirrors a greater picture of many Yemeni families losing loved ones due to the deteriorating health services.

Jaber today is trying to make sense of his new place in Turkey and he continues to immerse himself in more design and photography work.

Photography beyond borders

Social activist Yasmin al-Nadhri attributes her recent interest in photography to her lifelong passion for art and fashion. When she left Sanaa to go to Egypt for work just days before the war broke out, she had no clue that she would be leaving Yemen for good and would end up utilising photography as means to relate to the war in her country.

Her scheduled flight back to Sanaa coincided with the exact day that the Saudi-led coalition began its air strikes against Yemen; all flights home were cancelled.

With just the few clothes she had with her, al-Nadhri found herself stranded in Egypt. Due to the war and the increasingly tense security situation, she decided that going home was not a safe option and has not been back since.

During her travels for work going between Egypt, Germany, and Jordan, she kept a close eye on developments in Yemen through social media networks and has contributed to photography projects and initiatives taking place inside the country, including the #YemeniWomenBike (2015) and #YemenCoffeeBreak campaigns.

Her belief in the urgency of enhancing women's rights in Yemen compelled al-Nadhri to participate in the Yemen Women Bike campaign with photos not only intended to support the campaign but also to amplify women’s voices in the light of the war.

Despite her frustration of being stranded in Egypt, al-Nadhri created a photography collection depicting a Yemeni female in a modernised version of Yemeni women’s traditional outdoors-outfit known as sitar, while biking near the pyramids in Cairo.

“The context of Yemen at war inspired me to take this photo,” explains al-Nadhri, “seeing my country from far away being devastated by the war broke my heart. Yet, all the while our women and girls are fighting for their rights. I needed to show my support. I took the photo in Egypt hoping to show another side of the war and show that even stranded Yemenis want to show their connection to their homeland.”

When it came to the #YemenCoffeeBreak campaign, al-Nadhri again had the urge to participate in the campaign, despite being in Jordan. She went to the Amman Citadel and took a photo depicting a woman holding Yemeni coffee in the palms of her hand.

Al-Nadhri used the great resemblance between the Citadel and the throne of Queen Bilquis in Yemen’s Marib city. “While Yemen is increasingly becoming polarised and divided, more so each day, coffee was one of the few things that still united the people. Coffee was actually a message of peace for many of us who participated in the initiative,” al-Nadhri says.

“With both photos I thought it was important to show the role of photography in supporting and uniting our community; more specifically to show that photography goes beyond borders.” Al-Nadhri made the decision not to show her face in the photos to emphasise that the images could be timeless and conceptual.

Spanish artist Pablo Picasso once said: “Art is the lie that enables us to realise the truth.” The alternative narrative created by these photographers for what is taking place in Yemen is artistic, but it also seeks to tell a different truth. Between fiction and non-fiction, their work has empowered the photographers to fight despair and trauma.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].