Meet the Tunisian woman who made it onto Forbes 30 under 30 list

TUNIS - “Social entrepreneurs are superheroes,” Sarah Toumi tells Middle East Eye in a café in downtown Tunis. This is without a doubt a subject she feels strongly about, and she reiterates a point she has made several times in the past, including at a TEDxBarcelonaWomen talk that she gave in 2012.

"Social entrepreneurs are heroes; normal people who aim to change the world by doing something that will have a beneficial long-term impact on people’s lives," explains the 28-year-old who was recently nominated to Forbes’ list of 30 under 30 social entrepreneurs in Europe. "Social entrepreneurs are usually motivated by a vision and work in the dark," she adds, referring to the fact that they usually work in the shadows, hidden from the public eye.

When asked what it felt like to be on Forbes' prestigious list, she spoke about how it could help to jumpstart a national movement: "It was a great honour to be selected with amazing people like Malala Yousafzai. I believe being in this list is a type of consecration and means I'm doing a good job so it is really encouraging to go forward. Thanks to the Forbes list, skilled people, donors, administrators and media outlets have discovered my organisation Dream in Tunisia and my social enterprise project Acacias for All. All together we are now ready to create a national movement for climate change adaption in Tunisia and plant 1 million trees to fight desertification, poverty and gender inequalities."

For Toumi, turning her passion into a career path was a natural step. “I became a social entrepreneur at the age of twelve,” says Toumi as she recalls her family's first trip from France, where she was born, to her father's native Tunisia at the age of nine.

“I loved it,” she says. Her summers were spent in her father’s small village of Bir Salah, a three-hour car ride from the capital Tunis. Back then, with the encouragement and help of her father, the young Toumi would organise after-school and weekend activities such as homework clubs and trips to the seaside for the village’s children, as well as shipping around 300,000 books from France that children in poor rural areas would otherwise never have access to.

But not everybody in the village was encouraging. Initially the small girl from Paris was seen among the village’s 5,000 inhabitants as being too rebellious. “I was a little girl, but I was also a leader who told my cousins they could go to college if they wanted too, and protested when my grandparents told me to be respectful to the boys,” she explains.

This was an eye-opening period for the young Toumi, who as an outsider of the rural village had to learn the importance of how to respectfully express ideas and constructively approach challenges. It was already at this stage that Toumi began paying attention to the struggle of Bir Salah’s farmers.

Acacia trees for all

By visiting Bir Salah regularly over many years, Toumi bore witness to how the lives of farmers were slowly deteriorating as the desert started to creep in closer to the farmers’ land.

“Within ten years rich farmers became worse off and after a further ten years they became poor,” she explains.

Climate change, deforestation and the disruption of the ecosystem has made rainwater a scarce commodity. As a result, this has negatively impacted crop production which depends mainly on rainfall and groundwater. At the same time, groundwater contains high levels of salt that, if used for irrigation, threatens to kill the soil.

An increased understanding of this environmental struggle compelled Toumi to establish Acacias for All, which aims to improve farmers' environmentally friendly practices and ideas. Their approach includes offering alternative seeds to replace commonly cultivated crops, training farmers on permaculture and sustainable farming techniques, learning safe water irrigation practices and adopting new technologies for water treatment. The project is funded by the Belgian King Baudouin Foundation.

Toumi decided to introduce the acacia to farmers as the tree has unique qualities. It grows in the desert and has roots of up to 100 metres, providing soil with nitrogen that restores fertility. Using acacia trees against desertification is also an internationally recognised method used to halt the Sahara Desert from expanding and taking over villages and agricultural territory.

Initially, convincing farmers in Bir Salah about new farming techniques was not easy. Toumi went to her aunt, and together with a cooperative of women they managed to slowly gain the confidence of female farmers.

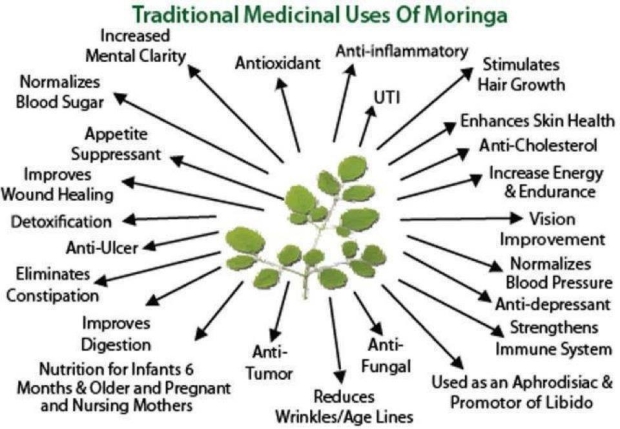

There is also an economic incentive to planting Acacia trees. After three years of growth, the tree produces Moringa oil and Arabic gum, both of which are included in a number of global industrial processes such as yoghurt manufacturing. Today there are 270 farmers, men and women alike, taking part in the agricultural cooperative.

At the initial stage of Acacias For All, Toumi was nominated as a young change-maker by the global social entrepreneurship network Ashoka’s Youth Venture and received training in business plan development. This paved the way for her to win the Youth Venture Prize in 2009.

Farmers pray for rain

The situation for Tunisian farmers continues to be strained. The agricultural sector accounts for about 9 percent of Tunisia’s GDP and employs 16 percent of the population. But some of the most commonly cultivated crops, including olives and almonds, consume large amounts of fresh water.

“Smarter and more localised farming along with diverse soil all working in harmony with natural cycles allows farmers to better cope with climatic hazards such as drought,” explains engineer Houcem Nabli in an email correspondence from his home in Sousse.

Nabli has years of experience working in the agriculture sector and is currently training Bir Salah’s farmers in organic farming.

“The recent environmental changes require an accompanying shift in farming practices to preserve the rural lands and compensate for the depleting water resources,” argues Toumi, who is hoping that acacia trees can be part of the solution.

“Planting different types of trees depending on the region and the climate is always a good idea,” Nabli said, emphasising that one principle in organic farming is to adapt and diversify different types of trees, which make them more resistant to climate hazards.

Nabli echoes the unique features of the acacias trees: “Certain microorganisms grow in symbiosis with the roots and enhances their ability to capture, store and retrieve water.”

So far Toumi and her team of six employees and 18 volunteers have planted 20,000 trees, of which 11,000 have survived - a good survival rate according to Toumi. Additionally, this year Acacias for All will recruit 20 ambassadors in different parts of Tunisia to introduce the tree and train farmers in their villages.

Acacias For All is also collaborating with the Ministry of Agriculture and the Observatory of Sahel and Sahara. With their help, the aim of planting 1 million trees on Tunisian soil by 2018 will hopefully be realised. By working closely with schools and teachers to create environment clubs and establish forest gardens, the project's focus is not only on farmers, but also Tunisian youth.

Local empowerment

Today Toumi’s initiative is self-sustainable and includes up to 100 children. The villagers all contribute without any external interference. Sustainability is crucial for Toumi who was brought up with a charity mind-set of “give, give, give”. She believes that communities can self-organise without having to rely on the assistance of outside charities or NGOs. “A community can get itself organised without outside interference. All you need is an idea and, step-by-step, change happens."

Toumi has lived with her husband and daughter in Bir Salah since 2012. She says living in rural Tunisia is not always easy, especially as a woman.

"If you are a young boy, you can easily take local transportation to the nearest village and sit in a café all day without raising any eyebrows," she explains.

According to Toumi, woman are not free: "If you are a woman on the other hand, regardless of your age, every step outside of the house will be questioned: What are you doing in the city? Where are you going? Why?"

She explains that many women also depend economically on other family members. She herself experienced scrutiny and ceaseless questions when she first came to the village and can see how it limits women’s movement.

“There is little space for dreams and hope,” says Toumi.

For this reason, Toumi created Dream in Tunisia, a community space where young people can share visions and ideas without being questioned.

“Here people will listen and pull you up and not push you down,” explains Toumi. Today there is a youth centre, a women’s centre and even an entrepreneurship centre.

“I had no idea about community work before,” explains 44-year-old Latifa Ismail in an email from Bir Salah.

She is one of the villagers focusing on empowering rural women and children. “This work has given meaning to my life by helping me to help others,” she said.

Flexibility is key

Toumi wants to show that you can be a career woman and a mother at the same time. However, she has had her challenges along the way. In 2014, she was convinced that her career as a social entrepreneur was over. Being a young woman who is half French and without a farming or engineering background has not been easy.

“You need to be flexible,” she says and then describes how she got new inspiration after the United Nations classified desertification as a global priority.

“Sometimes perhaps all doors are closed and you have to wait a bit before you see an opening; this was the door for me,” explained Toumi.

Realising that she was a link between her local environment and the global context motivated her again. In 2014, Toumi was invited to speak at the United Nations in New York. But despite the progress, Toumi does not appreciate the word "success".

"At the end of the day, it’s all about the long-term impact that you make," she concludes, "about your own future vision."

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].