Walking a tightrope: To be Yemeni, a journalist and objective

As a journalist and analyst, one of the cardinal rules of my work is to distance myself from the story – to not let it affect me. Initially, this was quite difficult. Over time, though, training yourself not to get too close to your subject becomes an almost reflexive instinct.

Over the past few months, my reporting has principally focused on the ongoing civil war in Yemen – my home country.

This has been exceptionally difficult.

While I’ve been keen to maintain the necessary professional distance in my journalistic reporting, it has been impossible to ignore the personal dimension the war represents for me. As the conflict grew in scale and intensity, my own personal involvement in it gradually widened too; expanding from mere journalistic reporting, to political analysis, to full-on campaigning and advocacy, in a desperate attempt to do all I can to help put a stop to the suffering of my people, suffering I’ve been a firsthand witness to for the past weeks and months.

When I was invited to represent the global NGO coalition Control Arms at the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) meeting in February, I could not possibly decline. I considered the impact I could have in helping bring the scale of the plight of my fellow Yemenis to the attention of powerful politicians.

Little did I know, however, that my pleas would fall on deaf ears. At the conference, our request to debate the Yemen case was refused. Instead, the ATT president suggested we discuss it in a few months, at the annual meeting in August. I watched incredulously as attendees spent the entire meeting debating mundane procedural points, having deemed the plight of an entire people unworthy of consideration. It was a sobering realisation though, sadly, not a surprising one.

Today, as Yemenis starve in their millions, the world continues to look away in silence.

Amidst the indifference, I have not stopped writing about the ravaged, bombed-out neighbourhoods in my hometown and other cities. Some of the displaced families I’ve visited and interviewed have included my own.

Make no mistake, though – my family has had it easy compared to the more than 22 million Yemenis who have spent the past few months on the edge of famine, and who remain, as I write, in desperate need of the most basic forms of humanitarian aid.

Over the past 12 months, I have seen people in my home country lose everything as a result of a tragic, senseless war between their own government, backed by a Saudi-led coalition, and Houthi rebels, backed by Iran.

The figures have been harrowing: Since the conflict began in March 2015, more than 35,000 Yemenis have been killed or injured. According to the UN, civilians account for almost 3,000 of the fatalities and 5,600 of the injuries, including 700 child deaths. The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs estimates that more than 2.5 million people have been internally displaced by the war.

Having witnessed the devastation firsthand, I have resigned myself to the most painful of conclusions: While houses and roads can be mended or rebuilt, and the dead can be mourned and honoured through monuments and memorials, the cost the current humanitarian catastrophe will inflict on future generations might leave our country beyond repair. Put simply, this war is tearing Yemen’s social fabric apart. Today’s children are putting down their school bags and picking up guns and rifles instead in alarming numbers. Faced with a future without prospects, many are opting to join extremist organisations such as Al-Qaeda – or even ISIS.

While Yemen - a land seemingly forever at war with itself - is no stranger to internal strife, this latest round has taken on an international dimension that makes it different from those in the past.

When President Abd Rabbuh Mansour Hadi fled to Riyadh in March of last year, he requested support from his regional allies and sponsors. Within days, they obliged by launching "Operation Decisive Storm," an aerial bombing campaign by a Saudi-led regional coalition.

However, what was meant to be a brief 10-day operation soon turned into a multi-pronged, multi-dimensional quagmire with no end in sight, despite thousands of deaths and the destruction of much of the country’s basic infrastructure. Predictably, heavy fighting on the ground has been accompanied by a full-blown political regional crisis.

In January 2015, Houthi forces seized control of the capital, Sanaa, triggering the full collapse of the internationally recognised government. Since then, civilians have been living under daily threat of attack. Coalition airstrikes have hit civilians and civilian infrastructure across the country, while Houthi forces and their allies have been shelling populated areas with regularity. The violence has not only degenerated into widespread violations of international humanitarian and human rights laws – committed by all parties – but to a severe humanitarian crisis that continues to worsen by the day.

However, beyond the local and regional parties to the crisis - the Saudi-led coalition, the Houthis, former president Saleh’s loyalists – one must not overlook the absolutely central role played by other international powers in fuelling and exacerbating the conflict.

While it is said that the Houthi rebels are backed by Iran, the United Kingdom and United States have been the largest arms providers to Saudi Arabia and its allies on the coalition side. Indeed, Saudi Arabia has been one of the largest arms purchasers over the past decade. In 2014, the country became the world’s largest importer of defence equipment.

Although many of the countries exporting to Saudi Arabia are states parties or signatories to the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT), a number of organisations, notably Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, have already produced strong evidence that US and UK munitions have been used in Saudi-led coalition air strikes against several residential neighbourhoods in Yemen.

In fact, a recent Control Arms report has estimated the size of arms licenses and sales to Saudi Arabia by European countries (France, Germany, Italy, Montenegro, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the UK) and the US to have been in excess of $25bn in 2015 alone. These sales include drones, bombs, torpedoes, rockets and missiles; in other words, the very weaponry currently being used by Saudi Arabia and its allies in their aerial and ground attacks in Yemen to commit gross human rights violations - and possibly war crimes.

Having failed to convince some of these key actors at the recent ATT meeting in Geneva, I am hoping they will read my pleas here: I implore all ATT signatory states parties to take action and lead by example.

Considering the urgency of the situation on the ground, any delays will have catastrophic consequences for an entire population. It is imperative they do not wait for the CSP meeting in August to take action. Instead, all states should cease any ongoing arms transfers to the warring parties in Yemen with immediate effect!

The world’s indifference, and complicity, must come to an end. The people of Yemen have suffered enough.

This piece originally ran in the Control Arms Blog.

- Nawal Al-Maghafi is a Yemeni/British journalist and filmmaker. She has had her work featured at Channel 4, BBC Newsnight, BBC World and BBC Arabic, amongst others.

Image: The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

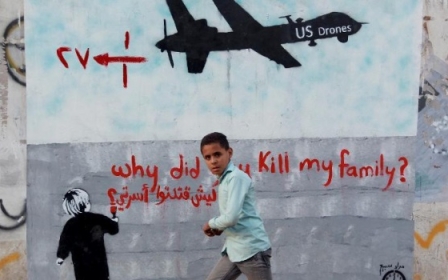

A Yemeni child looks at a mural which was painted by students in Sanaa University to symbolise the ongoing war in Yemen on 17 March, 2016 (AFP).

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].