How a Jewish cemetery is bringing a Moroccan village to life

AKRICH, Morocco - In the late afternoon, just as the sun begins to set, 39-year-old Abdulrahman hauls a bright orange garden hose at his side as he snakes his way up and down a hillside between trees of almond, fig, lemon, olive and pomegranate.

The evening watering routine is one of his responsibilities as the caretaker of this small community-managed nursery, located 20 km south of Marrakech in the rural foothills of the High Atlas Mountains in the village of Akrich.

His duties, however, include more than just gardening. He is also the guardian of the local Jewish cemetery, a recently restored burial site more than 700 years old that shares space with the nursery.

Inside the cemetery’s terracotta coloured walls, rows of organic fruit trees stand next to the refurbished gravestones of deceased members of Akrich’s former Jewish community.

The arrangement is part of an inter-communal initiative designed to preserve Morocco’s Jewish heritage and alleviate poverty in the area.

Land for the nursery was donated by the Council of Jewish Communities of Morocco to provide the predominantly agrarian community of Akrich with a source of sustainable income. In return, the residents protect and care for the property - also hoping that the restored burial ground will attract more visitors to the village.

The proposal to rehabilitate the Akrich cemetery and plant a nursery inside was first developed in 2011 with help from the High Atlas Foundation, a Marrakech-based organisation that works with disadvantaged rural populations across Morocco.

Initial reluctance

After five years of coordinating discussions between local residents, government representatives and Jewish community leaders, an agreement was reached between the parties, but not without some hesitation. Surprisingly, it was members within Morocco’s Jewish community who needed persuading at first.

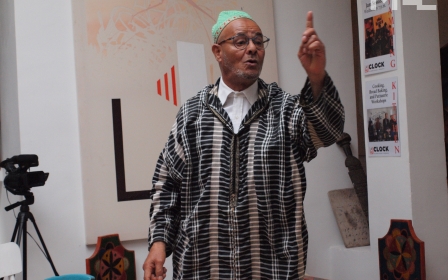

"It was challenging to identify local Jewish community leaders that would agree to the initiative and that is because it is new and atypical and it’s still taken time for people to understand its full implications,” says Yossef Ben-Meir, president of the High Atlas Foundation.

Ben-Meir, a former Peace Corps volunteer who has worked in Morocco since 1993, says that some of the initial reluctance can be explained by the urban-centrism of Morocco’s present-day Jewish populace, most of whom live in cities like Casablanca and Rabat.

“Like most urbanites, they are generally unfamiliar with the severe challenges of rural Moroccan people. The fact that hundreds of millions of trees are needed to overcome subsistence agriculture is not well understood.”

Ben-Meir is hopeful that the nursery will help Akrich break free of dependence on subsistence farming, which he considers the root cause of rural poverty in Morocco because in a modern economy it is no longer reasonable to engage in agriculture for food production and consumption alone.

To date, over 90,000 trees and saplings have been planted at the location, and an estimated 30,000 trees will be distributed to surrounding villages later this year.

In 2015, the governor of the region recognised the initiative’s potential, paving the way for its implementation at the national level. More than 12,000 Jewish gravestones at 167 similar Jewish burial sites have been restored across the country.

Akrich was the home to a thriving Jewish community of around 3,000 members that dates back to the 16th Century. Today, the cemetery is the only remaining visible trace of their presence here.

A sliver from the past

Like most Jews who fled Morocco, the community in Akrich left between the years of 1948 and 1970, following the creation of the state of Israel and the ensuing Arab-Israeli wars of 1956 and 1967.

In Ben-Meir’s opinion, the new Jewish state was successful in playing the regional turmoil to the advantage of its state-building project. “They were effective at convincing Moroccan Jews that Israel was the best option for them.”

Morocco’s own state-building efforts following its independence in 1956 were less effective in involving its Jewish citizens, contributing to their mass migration to Israel, Europe and the United States. The 3,000 Jews living in the country today are just a sliver of the quarter of a million from a half century ago.

Their absence is lamented by village residents, especially by elders, insists Abdulrahman. “The older generation of those in their 70s and 80s have positive memories of their old neighbours and only speak well of them. They lived side by side without any hatred or problems.”

Pilgrimage from the diaspora

In recent years, the Moroccan government has encouraged interfaith projects as part of its renewed commitment to promoting the country’s Jewish heritage, such as recognising the role of Hebraic influences in the country’s updated constitution in 2011.

The gestures have been directed in particular at the two million Moroccan Jews living abroad in the diaspora as government officials hope that their efforts to re-normalise relations will encourage some to return, either as sentimental tourists or even permanently.

While few have made the step to resettle in Morocco, Jewish tourism has increased in the last few years with sites like Akrich among the destinations.

Abdulrahman estimates that several hundred Moroccan Jews made the Hiloula (pilgrimage) to the village last summer, a turnout he considers quite high for the small village.

He says that most of the pilgrims come to seek a blessing of good health by praying at the tomb of Rabbi Ha Cohen, a saint revered for his healing power, while adding that others wish to leave Akrich with small branches from the large willow tree standing in the cemetery yard.

Yet Abdulrahman’s proudest memory of an encounter was with a middle-aged man sitting on one of the cemetery’s stairwells and admiring the idyllic view of the Atlas Mountains in the near distance.

“He told me that he has lived in Israel, France and the United States, but when he sits here he feels relaxed. He wondered why his family ever left here in the first place.”

Both Abdulrahman and Ben-Meir agree that the nursery has helped with leaving a favourable impression on visitors. Ben Meir says the fact that the land is being used distinguishes Akrich from other cultural sites and provides a sense of life that a museum may not.

“The site, even though it is a cemetery, is actually culturally and spiritually quite alive. The annual Hiloula draws hundreds of people from inside and outside of Morocco and they firmly believe that its spiritual energy is as strong as ever.”

The feeling is shared by Akrich residents explains Abdulraham. He says that the relationship is part of the village’s history that cannot be forgotten.

“As people of this village, the cemetery is also part of our heritage and it’s important that the younger generations understand this and keep it alive.”

'Preserving the sacred while advancing human development'

Even though the recent increase in pilgrims has sparked a greater appreciation for the cultural history of Akrich among residents, Abdulrahman does not shy away from acknowledging the work security the project has brought him.

In his case, the $300 he earns each month has afforded him a quality of life that is comfortable by village standards, allowing him to provide for his family of five and invest in purchasing a motorbike.

For many others in the village, however, he says they face critical problems related to poverty that are common throughout rural Morocco, such as a lack of electricity or running water and not having enough money to send their children to school.

“It costs $12 per day in transportation fees and meal costs to send one child to the secondary school in neighbouring Tamesloht. In families where there are four or five children, they are pressured to make decisions about who goes to school and who stays at home.” Often, it is young girls who are removed so that their brothers can continue their education, he adds.

Abdulrahman is hopeful, though, that the arrival of the nursery will help the village address their most basic needs and improve the standard of living for residents.

“For most people here, the challenges in life are about money. They want a higher income, better jobs, and to care for their children and family. It’s a difficult situation, but we are optimistic about the benefits brought by the nursery.”

Ben-Meir calculates that for each 100 trees planted in the nursery the average income for a family of nine will double, holding great potential for the community. Everything grown in the nursery is certified organic and sold at fair trade prices, ensuring that the village is not shortchanged by domestic or international markets.

From a chair in the reception hall of the cemetery, he is keen to emphasise that village residents are put in a position to retain control over all the decisions made related to the nursery, reminding both him and Abulrahman that they are due a community meeting sometime soon.

Outside of the cemetery and nursery, residents are proposing to run an irrigation pipe from the mountains to the village, while a committee of local women are in the process of setting up a labour cooperative for locally made crafts.

“In a certain respect, the success of this project is that it has managed to provide multiple Moroccan communities with access and control either over their culture, history, or livelihoods,” says Ben-Meir.

“This is what Akrich does. It preserves this “sacred” cultural site while advancing human development of the people and that is a key component of how Muslim-Jewish relations should evolve. As those relations are improved, so too are the life conditions of the people.”

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].