Syrian Mothers' Day: Finding hope through the new life of a child

DEIR ALLA, Jordan: Becoming pregnant and giving birth during a time of war clearly adds stresses to an already difficult time in a woman’s life, but mothers in and out of Syria say that the experience can also be a joyous occasion, and one that brings hope.

Whether one is living at home in Syria, or living as a refugee, bearing and raising a child is no easy matter.

This Monday, 21 March, marks Mother’s Day in Syria and other places in the Levant.

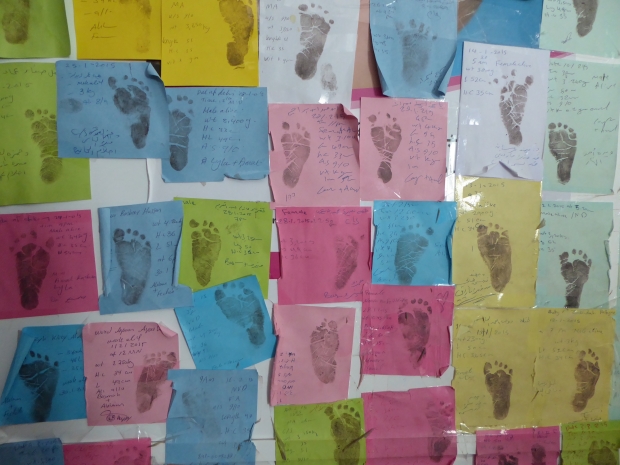

At a women’s health clinic in Deir Alla in the Jordan Valley, Syrian refugees and locals come to socialise and gather for handicraft classes and for post- and prenatal care.

Miriam, 20, originally from Hama province in Syria, is mother to one-and-a-half-year-old baby girl, Afra, who was born in Jordan as a refugee.

“Being a mother gives you the warm feeling that at the end of the day someone will call you ‘mama’.”

Miriam’s husband works in farming, but her parents are around to help her look after the baby.

But giving birth so far away from home was not easy, she tells MEE.

“The feeling of being pregnant is lovely, but not being in your country is horrible.”

“You don’t feel secure and you don’t feel you can give them everything they need,” Miriam adds. “God willing we will be able to return home soon.”

Having said that, Miriam says she does not practise family planning.

“I am not using contraception as I am still breast-feeding my baby. In any case, I do eventually want to get pregnant. I want to have four children.”

'Motherhood means love'

Nearby, Murjan, who is 19 and also from Hama province, has two children that were both born in Jordan. The eldest is one-and-a-half, and the youngest, Malsham, is seven months old and is with her at the clinic today.

“Her name means Damascus, the whole of Damascus. We named her this, hoping that we will go back one day.”

But she does not complain about the position she finds herself and her family in; her husband also works in farming, and so they have some income.

She also praises the clinic, funded by UNFPA, where she has come for an art class today.

“This clinic is great, it has really benefited us. It really helped during my second pregnancy.”

“I am happy here in Jordan, thank God, but I would be happier if we were back in our country.”

To Murjan, “the story of motherhood means love,” she says.

Kawthar, 31, has five children, the youngest of whom, Taybeh, was born in Jordan two years ago.

To her, being a mother means the world to her.

“Motherhood means everything to me. You feel that your children fulfil your life, they mean everything to me.”

Despite being in a precarious living situation – her husband also finds some seasonal work in farming in the fertile Jordan Valley, and they receive WFP food aid each month – her children raise her spirits.

“They help me to forget the challenges of life.”

Malnourished mothers and babies

Inside Syria, many expectant mothers are struggling with the physical burden of pregnancy, with the added psychological stresses of grief, displacement and loss. During the heaviest of Russian bombardments, a doctor in Homs province said that mother’s milk was drying up due to fear.

A recent report from Save the Children looked at the lives of children living under siege, and Hala, a mother in northern Homs said that, “The situation is miserable for breastfeeding mothers. There is no formula available and the breast milk is not sufficient because of the lack of nutrition. This is why mothers’ and infants’ health is so bad.”

In Misraba, in besieged Eastern Ghouta to the east of Damascus, Um Tarek echoed this danger: “A relative’s infant son died from malnutrition because of the lack of formula and food for children. His mother wasn’t able to breastfeed him because she was in such poor health herself.”

In the government-held Homs city, a new WFP programme is specifically targeting pregnant and nursing mothers.

“We are focusing on women who have borne the heaviest burden of the conflict in many cases,” says Dina El-Kassaby at the World Food Programme’s regional office in Cairo.

Through the SharetheMeal app, users can donate 50 cents - or more - when they themselves are having dinner, or whenever they like. This money goes directly to supporting mothers in Homs.

SharetheMeal previously raised enough funds to feed 20,000 children in refugee camps across Jordan for a full year.

Speaking to MEE, El-Kassaby says that mothers in Homs were the new recipient group chosen because in “many situations women have either had their husbands arrested, disappear, or they’re fighting. Many times their husbands have passed away.

“So we are now seeing a generation of children who are being raised by single mothers in an extremely difficult situation in many cases.”

But aside from funding, El-Kassaby adds: “We also need unimpeded access to all communities across Syria, no matter where they are.”

Hope for the future during war

Bayan, 18, is pregnant with her first child, and is a recipient of the food vouchers paid for with money donated by SharetheMeal users.

“Pregnancy is a beautiful feeling and it is the way to establish a family,” she tells WFP.

“I am very excited about this challenge as I am looking forward to creating a perfect, small family that will be well respected in my community.”

In a theme many mothers or mothers-to-be touched upon, Bayan says that her pregnancy allows her to look past the current state of Syria, which has just entered its sixth year of a devastating war.

Pregnancy, she says, “is also a strong way for me to forget about my fears during this dark phase of our lives and look forward to a different, more positive future.”

Nour is 24, and the mother to one-year-old Salam, which means “peace,” a name chosen in the hope that he will bring peace to their family, and to Syria.

“I lived a dream for nine months; each day I was preparing a list of the things that I wanted to buy for my baby, but it remained nothing but words on a piece of paper, because we can’t afford it,” says Nour.

Expecting her second child, Bushra, 23, describes pregnancy as a huge responsibility, and one that is not easy, “but it will bring happiness, as Dana will have a brother when he grows up and she can depend on his support as he will stand by her side,” she says, adding that the WFP vouchers have provided “crucial” support for her during the pregnancy.

“We lost everything because of the crisis, our home, my husband's trade, some of our relatives, friends and neighbours. But what empowers me is that my husband and daughter are safe and we are still together,” she adds.

“I am sure the baby boy will also bring positive energy to our life.”

Walla’a, is 28, and pregnant with her fifth child. She is internally displaced, having fled rural Homs nearly four years ago; half of Syria’s population have left their homes, either living as refugees or elsewhere in Syria.

At least a quarter of a million Syrians have been killed in the war, but some say the real figure is much higher and it has already cost $35bn.

But Walla’a sees peace on the horizon, by way of the younger generations.

“The crisis affected all the Syrians one way or another, there’s damage to the infrastructure and massive demolition that you see in Homs,” she says. “I believe it can easily be fixed, but for that to happen we need a generation who is moral, respectful and responsible to ensure our children and their children a peaceful life.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].