US-Turkey gap more visible during Erdogan's visit to Washington

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan arrived in Washington on Tuesday on a visit officially to attend a nuclear security summit and open a Turkish-built Islamic cultural centre in Maryland. But the main motivation of the visit seems in practice to be a public relations offensive: talking to sympathetic groups, particularly think tanks, about the open rift between Turkey and the US, two countries that have regarded each other as indispensable allies for over 60 years.

There are often tensions and disagreements in the Turkish-US partnership, two strong-willed allies with overlapping but never identical views of where they want to go. The US sees relations in a global context; Turkey, even before the war in Syria, always views them in terms of its neighbours and regional interests.

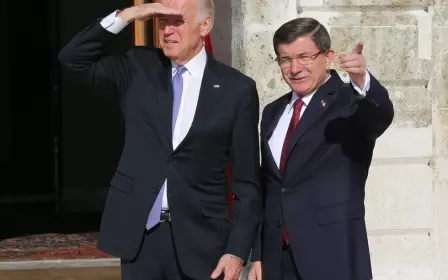

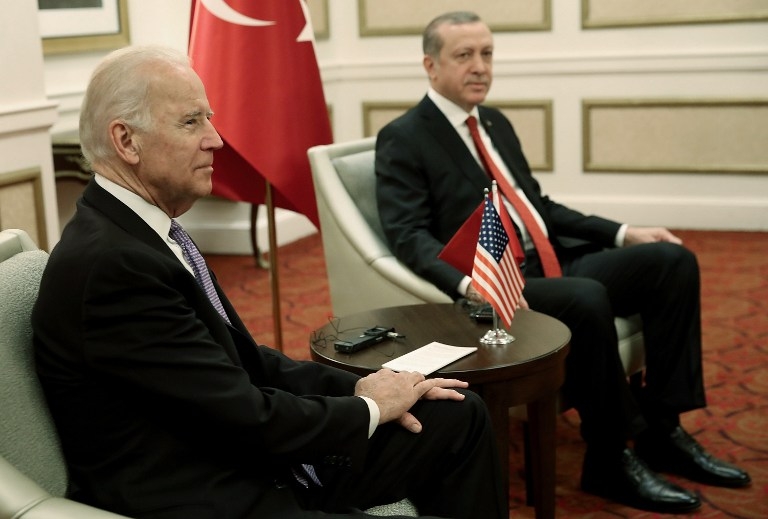

This time relations seem unusually rocky: though he has come at the invitation of US President Barack Obama, Erdogan will not be officially received by him at all but by Vice President Joe Biden.

Sections of the Washington press have been distinctly unfriendly in their curtain-raising articles about the visit, with suggestions that the US administration has been too late and too soft in its dealings with Erdogan. Thomas Friedman wrote on Wednesday in the New York Times that "our [the US] trying to make Iraq safe for democracy is requiring us to turn a blind eye to the fact that our most important NATO 'ally' in the region, Turkey, is being converted from a democracy into a dictatorship by its president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan."

Bloomberg's analysis was harsher still, asking "How Washington Got Turkey's Dictator So Wrong" and citing criticism from most (though strikingly not all) the ambassadors sent by the US to Turkey in the past decade and a half. Nor were reporters much kinder: one observer wrote: "After the president arrived in Washington on Tuesday night, his security team got right to work, harassing protesters and journalists outside his hotel, as writers for one of the papers recently shuttered by Erdogan's government noted."

Despite this, the Turkish president still has some staunch friends in Washington. Some remain because they will always side with the government of the day in a large and regionally powerful country like Turkey. Others specifically back Erdogan on what he clearly regards as the central problem dividing the two countries: the US refusal to treat the Syrian Kurdish PYD (Democratic Union Party) as a terrorist organisation, instead simply as an offshoot of the PKK (Kurdistan Workers' Party), the militant movement in Turkey which has been fighting a war in Turkey since 1984 in which tens of thousands have died.

Despite Erdogan's lukewarm official reception, with so far only a 45-minute meeting with Secretary of State John Kerry, there is continuing interest in encouraging the dialogue with Turkey to survive. So instead of a White House summit, Erdogan has had a spate of invitations to think tanks and similar gatherings, the most important being at the Brookings Institute in Washington at midday on Thursday.

From the days of the Ottoman Empire onwards, Turkish leaders on visits abroad have invariably talked directly to Western heads of government rather than "public opinion" or "opinion-formers" and institutions, so this is a significant departure from the usual pattern.

The new approach has been forced on Erdogan by growing unease and embarrassment at the series of restrictions on press freedoms and other liberties in Turkey, though it seems to have been skillfully organised as PR. Despite this, from the point of view of promoting Turkey's cause in the US, it is particularly unfortunate that the visit was immediately preceded by a formal demand to Germany to "delete" a satirical video film about the president - something which even Erdogan's good friend, the German Chancellor Angela Merkel, is completely unable to do.

State Department spokesmen who a few months were always tight-lipped and unforthcoming when questioned about freedom issues in Turkey these days are quite tough in their responses, though they continue to be uncompromising in their condemnation of the PKK as a terrorist organisation.

Fighting terrorism, especially when parts of Europe are virtually under siege from suicide bombers, offers better prospects of common ground. The Turkish president seems to have decided to concentrate while in Washington not on press freedom and civil liberties controversies but on the threat from terrorism and the need for the US to draw closer to Turkey and its goals in Syria.

However, for a visiting head of state to take a line that could imply direct criticism of the US government is hazardous. Turkey's foreign minister, Mevlut Cavusoglu, had apparently tried to soften things by declaring on Wednesday that the USA and Turkey should try to "convince each other" over their line on the Syrian Kurdish fighters.

But it seems that the president's personal message is more robust. Foreign Policy, one of the two main US international affairs specialist periodicals, reported in a blog late on Tuesday that during a dinner at the St Regis Hotel "a defiant Erdogan ripped the American media's coverage of his administration's policies and bashed the White House's support for Kurdish fighters in Syria".

Though this clearly reflects the president's strong sense of frustration and even injury, it is not a line that will easily win him converts in the war against the Kurdish fighters. Foreign Policy's report, which was quite detailed and quoted apparent eyewitnesses, was swiftly denounced as "baseless" by a report from the Washington bureau of the Turkish state news agency Anatolia.

Was there any alternative? At the back of the Erdogan's mind, there is probably a memory of his triumphant visit to Washington late in 2007, when, as Turkey's prime minister, he personally turned around four years of bad relations with the US after Turkish non-participation in the invasion of Iraq. But that was done through a direct visit to the then president, George W Bush, in the White House and successfully rekindling the friendship.

The approach then was so successful that the US supplied generous assistance to Turkey (most of it apparently intelligence) in its fight against terrorist attacks from the PKK and continued to do so for years afterward.

A success of this sort looks unlikely today with Turkey suffering serious isolation from the mainstream of international public opinion. That in turn is largely due to its unwillingness to adjust course over Syria - and the ending of the peace process with the Kurdish militants during last spring and summer. A visit to Washington under these circumstances offers more pitfalls than opportunities of success.

- David Barchard has worked in Turkey as a journalist, consultant, and university teacher. He writes regularly on Turkish society, politics, and history, and is currently finishing a book on the Ottoman Empire in the 19th century.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: US Vice President Joe Biden (L) meets with Turkish President Recep Erdogan on 31 March, 2016 in Washington, DC (AFP).

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].