What's behind the war of words between Iran's Khamenei and Rafsanjani

Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, recently launched an unprecedented attack on Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, Iran’s former president. Rafsanjani today leads a coalition consisting of the moderates – also known as pragmatists – and reformists in Iran.

On 23 March, a tweet on Ayatollah Rafsanjani’s Twitter page read: “The world of tomorrow is a world of dialogue, not missiles.” This tweet may have carried a special meaning, because on 8 March, the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) test-fired two long-range ballistic missiles that sparked uproar among American politicians.

Iran’s leader blasted Rafsanjani. In an angry 30 March speech, Ayatollah Khamenei said that those who believe the country’s future lies in negotiations rather than missiles are “either ignorant or traitors”.

Several sources in Iran interpreted these statements as an assertion that if Rafsanjani is ignorant, then he may not be fit for a high-ranking job. He currently heads the Expediency Discernment Council of the System (EDCS), an advisory body for the leader. And if he is a traitor, then it is clear how he should be dealt with.

The leader’s statements opened the doors for hardliners to attack Rafsanjani from every corner. Hardline Raja News wrote, “The leader of the internal current which aims to weaken the country’s defence capabilities is Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani. … Toleration of the compromisers (with the West) has come to an end.”

In this respect, Sadeq Larijani, the head of Iran’s judiciary and the man who, according to observers in Iran, is speculated to have the best chance of becoming Iran’s next leader, said: “The [political] stage should not be open on the individuals who seek to weaken and destroy the system’s military capabilities, its ideals and principles.”

Rafsanjani’s initial tweet was revised, and he said that his original statement was improperly stated. The revised tweet read, “The world of tomorrow is the world of the discourses similar to the Islamic Revolution’s, not intercontinental ballistic missiles and atomic weapons.” He added that “we haven’t had and do not have a better leader than Ayatollah Khamenei.”

Ayatollah Khamenei could have given Rafsanjani a private warning. But why did he instead opt to take the issue public and express his harsh judgement?

Killing several birds with one stone

After 16 years of being pushed to the margins – eight years (1997-2005) during the rule of the reformists and another eight (2005-2013) during the tenure of his arch enemy Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, Rafsanjani is rising like a phoenix from the ashes. Interestingly, he finished his presidency in 1997 as one of the most unpopular political figures in Iran. Today, however, not only the moderates but also the grassroots supporters of the reform movement have gathered behind him. Rafsanjani won over 2.3 million votes in the 26 February elections for the Assembly of Experts, the body tasked with the supervision and election of Iran’s supreme leader.

His votes exceeded any other candidate’s, running in the February elections for either Iran’s parliament or the Assembly of Experts (two elections were held simultaneously: one for the Assembly of Experts and the other for the parliament).

Rafsanjani has been at odds with Iran’s leader over imposing stringent controls on political and social liberties as well as Iran’s relations with the West, particularly the United States. He argues that interaction with the US as a superpower is necessary for the survival of Iran’s system. Iran’s supreme leader views the dominance of this school of thought in Iran as the death of the Islamic Revolution, of which he is the guardian.

Rafsanjani’s popularity and overwhelming votes as the leading figure in “the moderation current,” as they refer to themselves, which is in fierce rivalry with the conservatives, raised serious concerns in the latter faction led by Ayatollah Khamenei.

Rafsanjani could use his popularity as leverage to shape a powerful faction within the Assembly of Experts and win the chairmanship in the assembly’s internal elections. He could thus largely influence the election of the next leader and the trajectory of the country if Khamenei were to die during the assembly’s next eight-year term.

What made the picture more worrisome for the conservatives was the electoral elimination of leading hardline ayatollahs Mohammad Yazdi and Mohammad Taghi Mesbah-Yazdi – losing their seats in the assembly. The third leading hardliner, Ahmad Jannati, the secretary of the ultra-conservative Guardian Council which vets the candidates, was ranked last in Tehran and narrowly kept his seat in the assembly.

Moreover, despite the massive disqualification of the coalition of the moderate and reformist candidates by the Guardian Council, conservatives were shocked to learn that all 30 seats in Tehran in the parliamentary race were swept by the coalition of the moderates and reformists.

The above concerns aside, the realisation of the nuclear deal, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), was a heavy political failure for Ayatollah Khamenei. The agreement, reached on 14 July 2015 in Vienna, clearly violated the red lines drawn by Iran’s leader almost in their entirety. His grassroots supporters are still angry and continue to heavily attack the deal. On 5 April, Major General Jafari, the commander of the Islamic Revolution Guards Corps (IRGC), said: “The (JCPOA) is by no means an honourable document for the Iranian people. People accepted it reluctantly.”

To prevent serious damage to his stature as a result of the realisation of the deal, Ayatollah Khamenei has significantly intensified his critical position against the two leading figures of the rival camp: Rafsanjani and Iran’s president, Hassan Rouhani, a disciple of Rafsanjani’s school of thought. In a glaring example, without naming names, Ayatollah Khamenei sharply attacked Rouhani’s policies and vision in a speech he delivered for the occasion of the Iranian New Year on 20 March. This ostensibly largely appeased Khamenei’s grassroots supporters and conservative figures.

The moderates and reformists have shaped an undeclared unity, and the fault lines between them are now blurred. The moderation current led by Rafsanjani and Rouhani is a second wave, following the emergence of the reformist movement in 1997, and politically challenges the conservative establishment.

Ayatollah Khamenei’s critical position toward Rafsanjani not only satisfies the conservatives, but also silences him and limits his manoeuvrings. Meanwhile, it mobilises the conservative camp to actively enter the stage and confront the moderation current.

Iran’s leader also has a message for foreigners, especially Americans. The message goes rather like this: “If you think that because the moderates negotiated with you, laughed, strolled, and shook hands with you, our policies and hostile position toward you has changed, you are dead wrong. And if you were thinking that the realisation of the JCPOA will lead to the moderates gaining the upper-hand in Iran, you better think twice.”

In any event, solving the Rafsanjani issue will remain a challenge to the conservative establishment for months and years to come. It is expected that as the 2017 presidential election nears, the clashes between the two camps will escalate even further.

- Shahir Shahidsaless is a political analyst and freelance journalist writing primarily about Iranian domestic and foreign affairs. He is also the co-author of “Iran and the United States: An Insider’s View on the Failed Past and the Road to Peace”.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

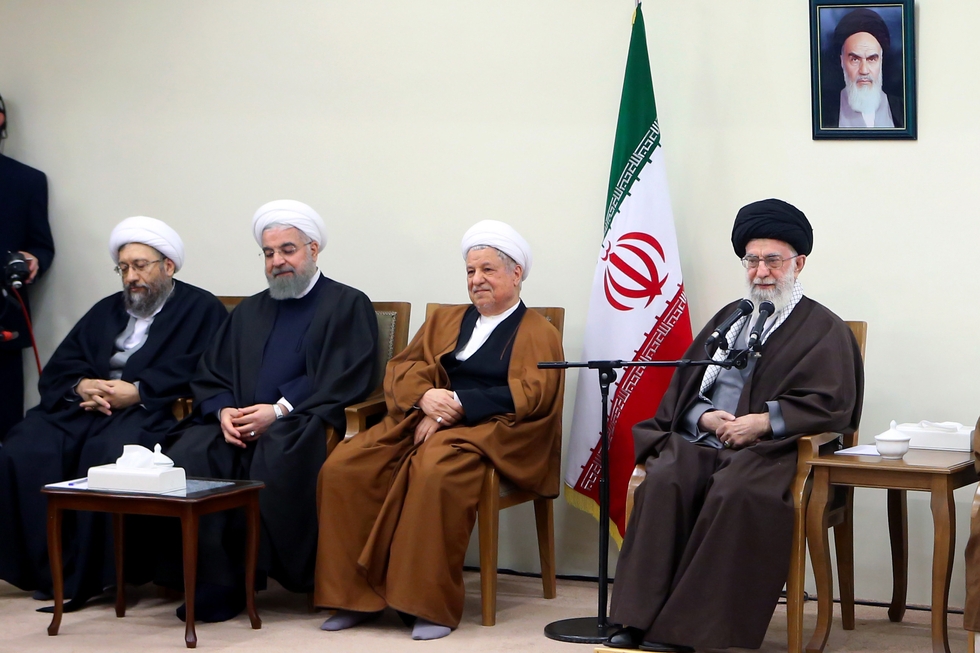

Photo: Iran's supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei (R) speaking with (L to R) Judiciary chief Sadeq Larijani, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani, former president Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani during a meeting with members of Assembly of Experts in Tehran on 10 March, 2016 (AFP/ KHAMENEI.IR).

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].