Egypt's unfinished contest between authoritarianism and popular resistance

Back in 2011 watching the revolutionary tide in Egypt, with the TV crews trained on Tahrir square in Cairo, there was the permanent nagging irritant that the complete story was not being told.

The Egyptian story was still one of the elites and one that occurred almost solely in the capital. As with other revolutions, the narrative was that this was a Pharaoh-only problem. If Mubarak goes, just as if Assad goes, the country will set itself on a forward, progressive path. The aftermath of Mubarak’s ouster was then just a simple story of the military against the Islamists.

Jack Shenker does a great service by challenging this narrative in the most profound way in an elegantly phrased tome that explains Egypt’s journey not over the last five years but over the last 50 or more. He demonstrates the extraordinary extent to which this was never a Mubarak-only problem and that indeed, perhaps most challenging of all, the international community as a whole must bear a large responsibility.

This is a work unashamedly devoted to the Egyptians as a people. It is not the life and times of the Presidents, Prime Ministers and Generals. Shenker takes us all over one of the world’s oldest countries to varying parts of the Nile Delta, to the Suez Canal to places where only the most dedicated reporters seem to go to.

By doing this, Shenker poses a vigorous challenge to the neoliberal orthodoxy. Ever since Anwar Sadat succeeded Nasser, Egypt’s economy has been opened up to the outside world to the extent that by the end of the Mubarak era, 336 publicly owned enterprises had been privatised. This may have been positive if these state assets were not being sold off at knock down prices to regime cronies and bastions of the military.

Ultimately they landed up in the hands of large multinationals, who benefited from the state determined to ensure that private capital trumped Egyptian rights, to the detriment of workers. Egypt was the “Tiger on the Nile,” lauded by the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and a Who’s who of World Leaders. In 2008, Egypt was named the World Bank’s top performer.

Shenker shatters the mirage and by doing so develops his theory as to why alongside Mubarak country. What Shenker terms, "Revolution Country" grew ever stronger. These revolutionary movements and actions were almost universally ignored by the outside world, hence the shock of the 18-days that shook the world in 2011. Workers’ rights were at the heart of this. In 2007, there was not one single day that there was not a strike somewhere in Egypt. In 2016, strikes are very much returning to the fore in Egypt, one reason why Shenker argues that the Sisi regime is far from secure and stable.

Shenker even breaks into a ceramics factory to investigate workers’ conditions and visits the largest textile factory in the Middle East at Muhalla, the site or perhaps the most powerful strike in Egypt’s history. He meets the Bedouin in the west of Alexandria at Daba’a who have reclaimed land expropriated to build Egypt’s nuclear reactor, recounting the brilliant campaign to highlight how dangerous and environmentally destructive the project is. This is highlighting new forms of political organisation and activism outside of traditional spheres – "Revolution Country".

The disconnect between the governing elite and the governed is at its sharpest when examining the range of mega-projects designed with foreign private investors in mind. Every year 1.5 million Egyptians are unable to find homes, even taking shelter among the tombs of the City of the Dead, and yet the state sees fit to build huge gated desert communities for the rich. These areas, one even called Dreamland, lie half empty. The real Egypt of the Ashwaiyaat, the informal settlements, is airbrushed out, the unplanned neighbourhoods built since the 1950s. The state’s mega projects seem a world away. Even today the Toshka project to create new settlements in the Western desert, is mockingly known as Mubarak’s pyramid. All these projects go forward with no consultations with the local population and no impact assessment of the environment and social cost.

Egyptians found themselves increasingly excluded from Egypt. Zahi Hawas, then Minister for Antiquities, banned Egyptians from going close to the pyramids yet hold car rallies and pop concerts there. The country’s heritage had become a commodity for international consumption. Many were forced from their homes by huge property developments.

Many Egyptians want to reclaim Egypt. To do so they also had to challenge the patriarchal nature of the country. Many had to challenge their parents to demonstrate. But this element is still there. Both Morsi and now Sisi acted as patriarchal figures.

The state was challenged but perhaps never seriously threatened. Another myth that Shenker challenges is that the Muslim Brotherhood was a revolutionary movement. Rightly he points out that, like the deep state, it is deeply conservative, very hierarchical and devoutly neoliberal. Many of its leading members were hugely wealthy businessmen like Khairat Al Shater, the original brotherhood choice for President. It co-opted the revolution for its own ends but protected elite power.

Perhaps at the one moment that the state was threatened in November 2011, it was the Muslim Brotherhood that saved it at the clashes in Mohamed Mahmoud Street, when Brotherhood members linked arms to prevent the revolutionaries getting to the army.

Similarly, both the state and the brotherhood had horrific records in treatment of women. Neither were going to challenge the rigidity of established gender roles. Perhaps it was no surprise then that women were at the heart of the revolutionary struggle not as women but as Egyptians. The then Minister of Interior, Habib El-Adly claimed remarkably that “Sexual harassment does not exist.”

Of course all his international admirers from Obama to Blair never mention that it was the then General Sisi who publicly defended virginity tests.

Shenker essentially presents the case that the passive Egyptian has not died after the counter revolution but actually never existed. Egyptians had protested for years against a state that spends twice as much on repression as it does on healthcare. Therefore, there will be a further round of revolutionary protest reflecting the division between those who want to return back to the old, and those who cherish the revolution.

Who knows when this may happen? The grim reality is that according to Shenker, revolutionaries face a Sisi regime that is wilder and more brutal even than Mubarak’s, the 700 death sentences handed out to Islamists so far proving the point.

More than anything this is a work that should be required reading for all those western leaders who so quickly dropped their temporary revolutionary rhetoric and betrayed Tahrir square. It should challenge all those who believe on such flimsy evidence that the choice was a simple one between the military and the brotherhood.

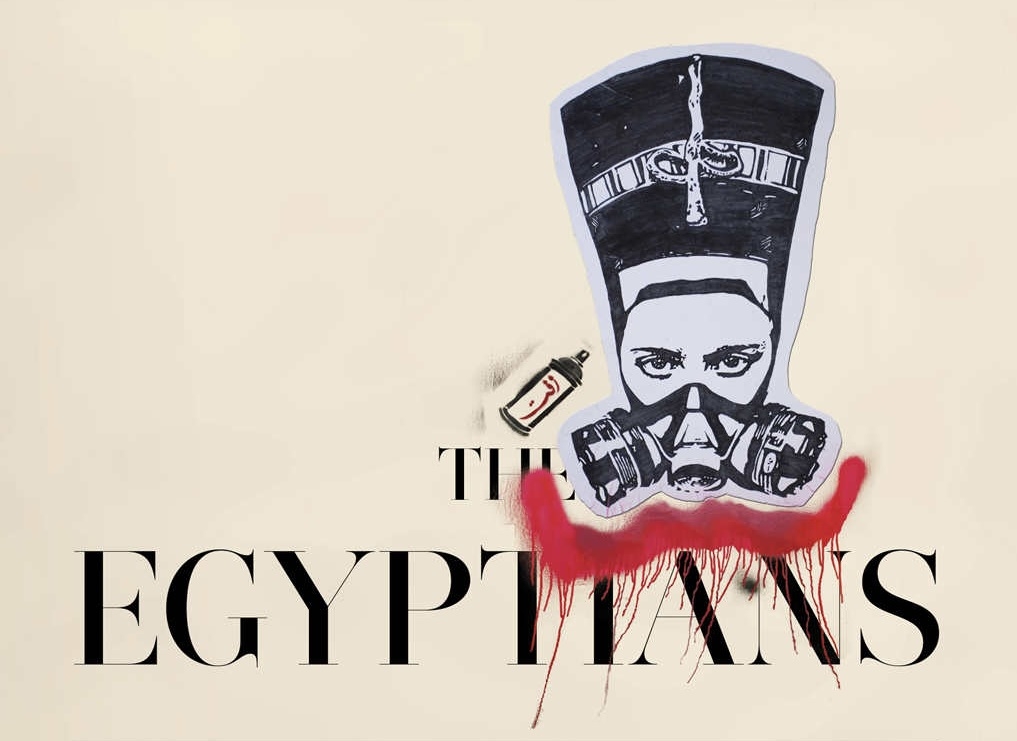

The Egyptians: A Radical Story by Jack Shenker (Allen Lane, London, 2016).

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].