Are Saudis prepared to drop Hadi to make peace in Yemen?

Watching their delegation stepping out of a private jet at Kuwait airport last week, it was obvious that the Houthis had come along way indeed; rising - in a matter of a months - from quasi-obscurity to reach unprecedented levels of prestige and power. “From the caves of Saadah to the mountains of Sanaa,” as someone might put it.

I was reminded of my first encounters with Houthi delegates, as they went shopping for suits on the streets of Geneva during the first round of peace-talks last year. It was the first time many of them had travelled beyond Yemen’s borders. Yet here they were today, stepping out onto a red carpet, greeted by top officials from the Kuwaiti Foreign Affairs ministry.

Although the current talks in Kuwait began over two weeks ago, there has been little progress. They had started with a wobble: the Houthi/Saleh delegation arrived three days late in protest at the fact the ceasefire nominally in place was not being respected by the other side. From the outset of the negotiations, they had always wanted a complete ceasefire, not a mere "cessation of hostilities". Once their delegates arrived in Kuwait, they spent the first two days arguing precisely this point.

Kuwait’s foreign affairs minister, who was desperate to secure a home-soil diplomatic coup for his country, immediately travelled to Riyadh for talks with the Saudis and, in the days since, despite reports of coalition jets patrolling Yemeni airspace, there have been relatively few air strikes since; a positive outcome already.

For many, this apparent shift in Saudi policy shows the urgency of reaching a settlement on their part. However, whilst there are mounting indications Riyadh desperately wants out of this conflict, several foreign diplomats I’ve spoken to insist that the Saudis are not willing to seek an exit at any cost; many are still expecting, or hoping for, some sort of victory.

Despite that initial three-day delay in Kuwait, direct talks between the Houthis and Saudi Arabia had been under way for weeks, already a major breakthrough. So far, these discussions have produced several confidence-building measures, including prisoner exchanges, and a ceasefire at the border. They have also delivered a cessation of hostilities – both of Houthi cross-border attacks and coalition bombings in North Yemen – that has held since.

“Riyadh is where the talks are really happening,” a senior diplomat told me. What about President Hadi and his government? I asked. “At some point, they will have to accept that they have to go,” he replied. I was reminded of recent reports from Yemen suggesting many of Hadi’s ministers have been busy selling their properties and assets in the country. I wanted to tell him they had seemingly come to terms with their fate, and are merely buying time now.

No longer fighting for Hadi

But if the Houthis and the Saudis cut a deal, I asked the diplomat, what would happen to the forces on the ground fighting for Hadi, such as the militias in Taiz and Aden? “I think we have known for a while now that they aren’t under Hadi’s control, and they most certainly are not fighting for him,” he responded.

This was something I had considered, and written about, before but had always refused to believe. To hear it stated so bluntly by a senior diplomat was shocking. The notion that the dozens of armed militias currently operating across the country were under nobody’s control was too frightening to contemplate, and confirms fears that even if a peace deal is struck Yemen might not see peace for years, possibly decades to come.

International criticism of Saudi Arabia has been intense, with coalition air strikes responsible for the majority of civilian casualties, including a 27 February airstrike on a marketplace in Sanaa that killed at least 32 civilians, and a 15 March airstrike on a second marketplace in Hajjah which, according to media reports, killed at least 106 people.

On 25 February, the European Parliament adopted a non-binding resolution calling for an arms embargo on Saudi Arabia. A month later, on 22 March, eight NGOs, including Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, issued a joint statement calling on all governments to cease the supply of arms to all parties in the conflict. At a press conference, Human Rights Watch stressed in particular that the P3 Council members - the US, UK and France - should stop sending arms to Saudi Arabia until the latter ends its “unlawful” air strikes and credibly investigates alleged violations.

Amid this mounting international pressure, there’s been persistent talk of an imminent UN Security Council resolution on Yemen. However, the threat has proved largely empty in light of Saudi Arabia’s significant political leverage at the UN.

Earlier in March, Security Council members, led by New Zealand, began discussing elements of a resolution covering issues of access for humanitarian aid and the protection of civilians, but the resolution was “put on hold in light of political developments”. Nevertheless, the threats did prove to be an effective catalyst in forcing the Saudis and the Hadi government to the negotiation table, as well as later bilateral talks between the Houthis and the Saudis.

Nevertheless, slowly but surely, with every round of talks, a step forward is secured. We have come a long way since the shoe throwing and boycotts witnessed during the first round in Geneva. The second round, though it failed to produce a deal, successfully broke the ice and saw both parties meet in the same space for the first time.

It is this third round of talks in Kuwait, however, where the heavy lifting truly begins. Both sides have agreed on a five-point plan based on UN Resolution 2216 which stipulates the following:

- Withdrawal of militias and armed groups

- Handover of heavy weapons

- Interim security arrangements the restoration of state institutions

- Resumption of inclusive political dialogue

- Establishment of committee for prisoners and detainees

However, the problem isn’t these points themselves, which both delegations have already accepted, but how to implement them: whether this should be done sequentially or in parallel with the political process. How this particular impasse is resolved will probably decide who has ‘won’ or ‘lost’ in this conflict.

The Houthis are adamant that the plan should be implemented in parallel with the political process, notably the formation of a government, or state body, that is inclusive of all factions, to hand over weapons to. The Hadi government delegation, however, believe a weapons handover and withdrawal from the cities by the Houthis – to total surrender in all but name - is a crucial pre-requisite for the political process to begin. An option that the Houthis, having come this far in the conflict, are unwilling to consider.

For its part, Saudi Arabia’s recent moves, reducing their military air strikes and cutting a deal with the Houthis to secure its borders with Yemen, has shown their good faith but has also raised questions as to whether the Saudis still share the same agenda as the Hadi government, putting the latter in a very delicate position.

Will Saudis drop Hadi?

Will the Saudis maintain their support for Hadi? Or are they about to cut their losses and strike a deal with the Houthis behind closed doors?

In recent developments, Houthi forces, keen to show they are both able and willing to continue fighting, launched an assault on the Umaliqa base on Sunday, killing several soldiers, breaking the ceasefire they had so adamantly pushed for. Unlike most other government soldiers, those at Umaliqa had refused to take sides in the war between the Iran-allied Houthis and the Saudi-backed Hadi government.

The Houthis, who had tolerated this neutrality until now, launched a surprise push into the facility in Amran province and seized its large cache of weapons at dawn. This was clearly to provoke and intimidate the Yemeni government, which responded by suspending direct talks with the Houthis, though without pulling out of the talks altogether.

“We’re trying to cool the situation down as quickly as possible,” a source close to the Houthi-allied General People's Congress told me. Another source, a Houthi official, later insisted that the Saudis and Hadi loyalists “have to understand we will keep on fighting if we have to.” This reminded me of something a Houthi leader once told me, when we met in Saadah five years ago, “We will fight till the last man standing.” A terrifying prospect.

Houthis' shift in tone

A recent change in the tone in Houthi announcements regarding Saudi Arabia already shows that a deal, whatever the details, is already in motion. In a particularly interesting interview with the Saudi newspaper Alwatan which was followed by others on the BBC and the Houthi broadcaster AlMasira, Mohammed Abdelsalam, head of the Houthi delegation, referred to Saudi Arabia as Yemen’s neighbour and “older sister”. The phrasing was so unexpected there were rumours his words had been twisted or taken out of context. I was sceptical too, and decided to ask him. Had his comment been fabricated? “No”, he told me with a sly smile.

Even the United Nations has hinted at a change in position. Whereas previous statements called for a handover of weapons to the “Yemeni government,” a recent statement instead referred to the transfer of weapons to “state control”.

Put simply, this current round of talks is, as the UN envoy has repeatedly put it, “the closest Yemen has gotten to peace”, and represent possibly the last opportunity for parties to the conflict to reach a solution through diplomatic means.

Broadly speaking, there are two ways events can go from here. Either the Houthis realise that this is as good as it is going to get for them, and the Yemeni government come to terms with the fact they will never be able to return to Yemen (realistically, do they even want to?); or both sides decide to keep fighting on the ground, inflicting yet more human suffering and a total decimation of the economy. This is not alarmist hyperbole: 50 percent of the population is already nearing famine, and the consequences of further collapse are too terrifying to imagine.

Prior to travelling to Kuwait to cover this current round of peace talks, I was reading about the Bosnian tragedy of the 1990s, and was struck deeply by one particular quote. As he sat around the table for a third round of peace-talks, Bosnia’s then-president, Haris Silajdzic, thought to himself, “I hope that this time they brought their conscience with them.”

As I leave Kuwait, I am constantly reminded that the situation on the ground in Yemen continues to deteriorate. I cannot predict whether my homeland will see peace soon, but all I can hope for is that when the delegates turn up at the talks tomorrow, they will bring their conscience with them.

- Nawal Al-Maghafi is a Yemeni/British journalist and filmmaker. She has had her work featured at Channel 4, BBC Newsnight, BBC World and BBC Arabic, amongst others.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

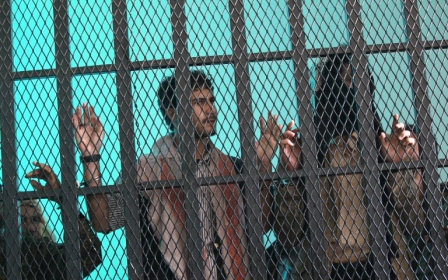

Photo: A Yemeni artist paints a graffiti on a wall in the capital Sanaa in support of peace in the war-affected country, on 30 April, 2016 (AFP).

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].