British drone strike policy: 'Confused and confusing'

Drone strikes have become the weapon of choice for Western governments over the past decade, but let’s face it - there are problems that occur when a lethal war-like force isn’t governed by law.

Drone strikes are a cheap and less risky option for governing bodies hesitant to deploy troops. A drone pilot can wake up in the morning, have breakfast and even be dropped off to work by his wife, and still participate in targeted killings across the globe sitting only a few miles away from his family home. But as the UK drone debate pendulum is in full-swing, many of those involved in this issue are asking: is any or all of this legal?

The UK Parliament's Joint Committee on Human Rights (JCHR) published its report on the use of drone targeted killings on Tuesday and claimed that the drone policy was “confused and confusing”. The UK position lacks a proper understanding of the application of international law, drone strikes and asymmetric warfare.

In the fast-paced world of counter-terrorism-led means and methods, the application of law should not be confusing or misunderstood. Historical principles of distinction, necessity and proportionality, laws and international conventions should not be blurred with combating terrorism.

The policy as it stands “may expose … ministers to the risk of criminal prosecution for murder or complicity in murder," says the report. Parliament, the public and state agencies involved in drone targeted killings need to know whether the government is complying with the international law and to provide absolute clarity for all those involved in the chain of command for counter-terrorism strikes – MI5, MI6, armed forces, officers and ministers and others – so they have a legal defence against any possible future criminal prosecution for murder within or outside of the UK.

The report raises concern that the ongoing uncertainty about government policy may leave front-line intelligence and army personnel in considerable doubt about whether what they are being asked to do is lawful, therefore exposing them, and ministers, to the risk of criminal prosecution for murder or complicity in murder.

The JCHR report concluded, “As the world faces the grey area between terrorism and war, there needs to be a new international consensus on when it is acceptable for a state to take a life outside of armed conflict. The UK government should lead in the establishment of that consensus and thereby ensure that states are able to take the action which is necessary to protect their citizens without breaching the rule of law.”

UK applying war law outside war zones?

The JCHR report follows the killing of British national Reyaad Khan in August 2015. Although not the first British drone strike overseas, directly or via acquiescence in US strikes, the Prime Minister David Cameron publicly admitted that two British nationals Reyaad Khan and Ruhul Amin were killed by an RAF drone strike on 21 August in Raqqa, Syria – whilst travelling in a vehicle. This was the first time a British prime minister had made a public declaration for the use of drone warfare by the UK.

Belgian national Abu Ayman al Belgiki, who was also travelling with Amin, was killed in the vehicle. A third British national Junaid Hussain, 21 was also killed in a joint US operation three days later. The US Central Command revealed that a previous attempt in targeting Hussain resulted in killing three civilians in the “vicinity” of the strike, although the British government did not confirm its involvement.

'The government executed my son'

Meanwhile, Reyaad Khan’s mother told me that she is still waiting to know why her son was killed:

“I was devastated to hear that the government executed my son without putting him on trial. I know that my son was not a threat to any one of us. The government killed my son without reason and has never even attempted to come to see us or offer any explanation.”

The JCHR concluded that the drone strike targeting of Khan was part of an armed conflict with the Islamic State group based in Syria and Iraq and consequently governed by the Laws of War. But there appears to be a deep discrepancy with the language used by the UK government, between Parliament, UN and lawyers seeking scrutiny.

In 2014 the House of Commons mandated that the UK could strike the Islamic State group in Iraq, having voted against any military operations in Syria in 2013. If the UK intended to target any military objectives in Syria it would need a separate vote by Parliament. Hence, all strikes at the time must be considered as beyond an armed conflict, giving way to the application of Human Rights Law to govern drone strikes. The parliamentary vote to support military action against IS in Syria did not take place until 2 December.

The British government’s policy is that “the use of lethal force abroad outside of armed conflict for counter-terrorism purposes is lawful if it complies with (1) the international law governing the use of force by States on the territory of another State, and (2) the Law of War.”

But the Law of War does not apply outside armed conflict zones. The correct legal framework that applies is Human Rights Law, and in particular the Right to Life in Article 2 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). The government must review its legal basis, and clarify the law that governs drone strikes outside of armed conflicts. There must always be a higher threshold for taking life beyond warzones.

Drone strikes can only be lawful outside of armed conflict zones if there is a concrete, specific and imminent threat posed to British national security – this concept is governed under International law of self-defence.

The government needs to clarify its interpretation and understanding of "imminence". Holding a broad scope of imminence can simply be dangerous, and result in targeting individuals without concrete evidence of hostility. All threat issues, unless exceeding imminence threshold level, must be dealt with by less harmful means, such as capture. This is simply because whilst the law of self-defence under international law permits the use of force to avert harm, this cannot be extended to pre-emptive drone strikes against a threat that is insignificant or “plans which have only been discussed but lack the necessary intent or capability to make them imminent”, the JCHR highlighted.

Conflicting messaging on 'armed conflict'

The UK government seems to be projecting conflicting messaging and differing reasons to Parliament, the United Nations and law firms seeking judicial review on the context of the counter-terrorism drone strike policy.

The prime minister confirmed to the House of Commons on 7 September that it is the government’s policy to be willing to use drone strikes outside of armed conflict, for example in Libya and other places. Although the government denies having a drone policy, it is clear that there is a policy to execute drone strike outside of war zones for counter-terrorism purposes. The government refused to clarify detailed questions on the legal framework and provided differing reasons to the United Nations and Parliament, the JCHR mentioned.

In a statement to Parliament on 7 September 2015, David Cameron said that the drone strike killing of Reyaad Khan was a “new departure” because it was the first time the country independently used force outside the context of an armed conflict. The JCHR report confirmed that that the secretary of state confirmed that the prime minister told the House of Commons that “this was the first time that we have acted in an area in which we were not previously involved in an armed conflict”.

However, in a letter dated 7 September to the UN Security Council the UK Permanent Representative to the UN said that the drone strike in Syria was not only in self-defence of the UK but was also in exercise of the right of collective self-defence of Iraq - this suggests that the strike was executed as part of the armed conflict with the Islamic State group which the UK was engaged with.

Again, in a letter dated 23 October from the Government Legal Department to a British human rights firm, in response to a claim threatening judicial review proceedings, the government’s lawyers similarly asserted that the strike in Syria was part of an armed conflict.

Although the self-defence arguments may have standing, there is conflicting language projection between what the prime minister said to parliament and what he said to the UN. This has implications for the application of the correct legal framework to determine the legality of any strike.

The British government’s lack of answers on the committee's questioning demonstrates how the drone policy is following in the shadows of the US drone fiasco. The US government has taken a dangerous path of drone targeted killings in countries they are not at war with, such as Pakistan, Somalia and Yemen. The targeted killing programme is deemed to have claimed the deaths of hundreds of civilians, although the strikes are shrouded in secrecy. The former head of the US Defence Intelligence Agency said the drone programme is a “failed strategy”.

We should welcome the JCHR report as it moves the debate on drone warfare forward and seeks fundamental responses from the government on the policy. The report asks questions on critical issues such as applicable laws, transparency, accountability and the need to take international leadership on a consensus governing armed drones.

Ultimately, the British drone policy must hold fast to the rule of law - not blurring the lines between counter-terrorism law enforcement and war-like military strikes.

- Khalil Dewan is a Legal Officer with expertise in International law, human rights and national security. He has a special interest in lawfare and works on international counter-terrorism policy. He has investigated the use of drones in modern day warfare and actively works to encourage the rule of law, due process and accountability. You can follow him on Twitter @KhalilDewan.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

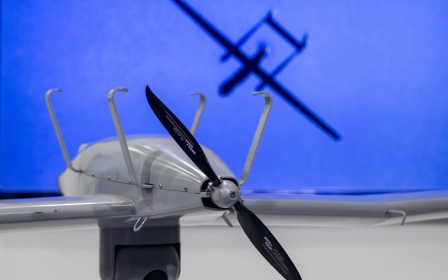

Photo: A US drone is pictured at the Farnborough Air Show in Hampshire, southern England, on 16 July, 2014 (AFP).

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].