Breaking the silence: Tunisian festival gives voice to women in struggle

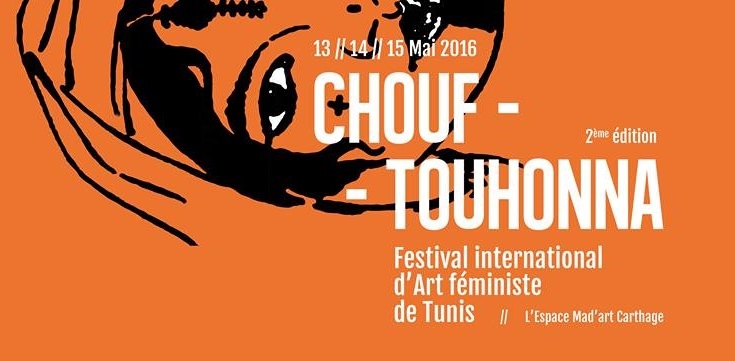

“Too many women in too many countries speak the same language: silence,” read the poster at Chouftouhonna, an international feminist art festival that concluded on Sunday in Tunis. The festival, which brought together 116 artists from 37 countries, is in its second edition, after last year’s event proved enormously popular. For three days, hundreds of visitors watched films and dance performances, sat-in on panel discussions, danced to music and attended workshops for free.

Chouftouhonna, which means “I saw them” in Tunisian Arabic, was deliberately created to be “inclusive… It’s a place with no paternalism, heteronormativitgives voice ty... we’re offering a space to feel safe,” activist and journalist Khouloud Mahdhaoui, one of the founders of the festival told Middle East Eye between performances.

Organised by Chouf, a Tunis-based feminist organisation “working for women’s bodily and sexual rights in Tunisia,” the festival has a decidedly international flavaour, largely ignoring nationality when selecting participants. “Of course we encourage everyone,” Mahdhaoui said, “but more [so] women from the global south, because there are a lot less spaces [there].”

The concept of differing realities cropped up several times during the festival, but the juxtaposition of women’s lives around the world did not serve as a dividing factor. It was an opportunity to listen, exchange and think critically.

At a roundtable discussion identifying different perspectives on feminism, organised by Anna Antonakis, a Greek-German researcher and president of the Rayhana Feminist Association of Jendouba Women, the conversation focused on deconstructing monolithic notions of feminism singularly based on gender.

Atiaf Alwazir, a Yemeni activist and writer, spoke about her involvement with Tahrir Square protests in 2011. Initially “a time of collective resistance,” gender-based violations began to emerge. “As women we are taught that our desires, our needs, come in second place,” Alwazir said, noting that in Tahrir Square, women’s demands were not taken seriously by their fellow male activists, because there were "other problems".

This artificial hierarchy of importance was echoed by Hayat Amami, who runs the association Victory for Rural Women in Sidi Bouzid, the central Tunisian town widely considered the birthplace of the country’s 2011 revolution. Amami noted that in her community, despite the enormous responsibilities women have, they often don’t feel like they can take decisions for themselves. Restrictions imposed on women, be they self-inflicted, economic, cultural, or societal, are obvious obstacles to their individual and collective actualisation. “I don’t want to become a man,” Amami said matter-of-factly, “I just want to be a powerful women.” The audience, which was mostly women, clapped loudly.

The personal is political

That the notion of "woman" can change over one’s lifetime was a concept touched on by Alwazir. A new mother, her recent pregnancy coincided with the ongoing war in Yemen. She spoke candidly about the issues she now faces as a mother, things as innocuous as breast feeding, which has proved uncomfortable to do publicly in Tunisia. “We tend to not give importance to the everyday activism,” Alwazir said passionately. “These should be celebrated...the personal is political.”

Sitting in the audience, it was easy to feel the sense of security Mahdhaoui spoke about. The panelists spoke honestly and from a deeply personal place. “Thank you for inviting me to represent the white privileged European position,” Marit Ostberg, a Swedish feminist activist said with a self-aware chuckle. Audience members were invited onstage to comfortably recline in a red armchair to ask their questions.

Several of the art performances were equally as engaging, challenging pre-conceived conceptions of what it means to be a woman. In one gallery, a series of black and white photographs by Tunisian artist Sana Chabaane show an old woman, her liver spots a darkish gray, her short, white hair softly waved up off her high forehead. Her gnarled hands are wrapped around a smooth, plastic baby doll, its vacant eyes staring out from a knit cap, in a hauntingly beautiful maternalistic circle of life.

One particular film that stood out was Chouf, a beautiful Tunisian short directed by Imen Dellil. The film followed a blind couple raising their two young boys in poverty. It showed the audience, in colour-saturated high definition, a life that the couple themselves cannot see. Dellil utilises close-up shots of groping fingers, trickles of water, and gas flames to give us a sensory experience of the couple’s life.

Chouf was later followed by Unos Quantos Piquetitos, a Greek black and white film directed by Menelas Siafakas. Piquetitos’ narrator takes us through a normal day in her life, from catching her morning transport to dealing with clients to grabbing coffee with a friend. From the moment the narrator climbs out of bed, a large copy of L’Empirica clearly visible on her nightstand, she recounts incidents of domestic violence around her country. She injects stabbings and shootings by fathers, jilted lovers and co-workers into her conversation with people, only to be ignored. Over the course of the film, the narrator becomes increasingly angered by people’s determined silence in the face of violence.

Outside the cinema, one could hear music and applause, people laughing and talking, eating and drinking. For three days at Chouftouhouna, there was no language of silence.

Chouftouhouna ran from 13-15 May in Tunis at Mad’Art Carthage. The festival will be back for its third edition in 2017.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].