Mental illness in Lebanon: A life sentence

ROUMIEH, Lebanon - A military rhythm is beating out. Drums are rolling and trumpets are blaring. Prison wardens from Unit A are perfectly lined up as they solemnly welcome senior military officers and internal security forces dignitaries attending the premiere last month of the therapeutic play Johar… Up in the Air, directed by Zeina Daccache, and starring 38 prisoners from the Roumieh Prison.

A giant iron door opens up, and then another one, and the attendees now enter the prison courtyard which is guarded by riot police.

One, two, one, two. The beat plays out.

In complete silence, prisoners from the shadows of their cells are keeping all eyes on the little flock of officials that are making their way to the art-therapy room of Lebanon’s central prison, where 3,500 prisoners are languishing in a building that was originally built for a maximum of 1,000 inmates.

Life sentence cycle

“When you are strange, no one remembers your name,” - The chorus of The Doors’ song People are Strange welcomes the audience. The director of the theatre greets every man of power present that night one by one, making sure they are seated in the front row. Facing them on stage, a prisoner with mental illness kindly gazes upon them.

The lights go off and suddenly the rhythm enters a cycle, the same kind of cycle prisoners sentenced to life and the ones who suffer from mental illness find themselves stuck in. For all of them, time is suspended, literally “up in the air”. Their lives drift away, with no hope of a new beginning. For the former, it is simply because they have been sentenced to life. On the other hand, the latter are still here only because, according to article 232 of the Lebanese Penal Code, a “mad” prisoner must be incarcerated into a special psychiatric unit until the court decides to put an end to it, based on evidence that he “has been cured of his madness”.

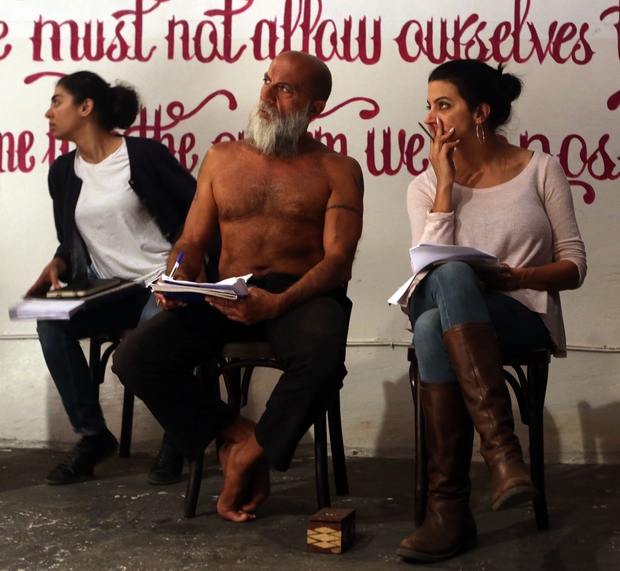

Between each skit, the actors gather up and start to repeatedly mime the same actions to illustrate their life-sentence frustration: one is pacing while talking to himself, another is chanting, an elderly man is screaming with his head in his hands, and another man is reading legal documents with his eyes wide-open.

Founded in 2007 by Zeina Daccache, Catharsis, the Lebanese Centre for Therapeutic Theatre, has been organising theatre workshops with 70 of these men whose lives are being forgotten about behind bars.

“Where are the actors?” This is the question she asked herself when she first stepped into the overpopulated prison. After graduating from a school of dramatic arts, she wanted to create another type of theatre. “I was bored of the unfruitful theatrical cycle, where everybody plays the same well-known plays from well-known writers, but with no direct connection whatsoever to reality,” she says to Middle East Eye.

Therapeutic theatre and legal change

In Roumieh in 2007, Daccache started a therapeutic theatre workshop that would lead to a play called Twelve Angry Lebanese. Then, in 2011, she went to the women's prison in Baabda to cast the prisoners in her play, Scheherazade in Baabda.

Each theatrical creation is aimed at providing psychological support for prisoners. By inviting ministers, members of parliament and military officers to her plays, Daccache is also aiming to publicly point out the legal loopholes of the prison system that contributes to worsening the already sad fate of prisoners.

Twelve Angry Lebanese brought the issue of the reduction of penalties for good behaviour, which was passed in 2002 but "had dropped out of sight" according to one of its authors, back onto the agenda, says Daccache.

With Johar...Up in the Air, Daccache wishes to put an end to another piece of legal nonsense: article 232 of the Penal Code, written in 1943, which allows detention until “madness has been cured”. In fact, this is like a life-sentence.

That law is the remaining stronghold of an anachronistic view on mental illness in Lebanon, says psychologist Hala Kerbage to MEE. “Mental illness is viewed as incurable and antisocial in our current legal system, which rests on a 1983 law that neglects the rights of patients and insists on institutionalisation. Since 2008, several specialised NGOs have been working on a new law about mental health issues in favour of rehabilitating patients, rather than keeping them locked. In the end, the bill was tabled two months ago. Even if it does pass, 10 to 20 years will be necessary for a proper application of the law,” she reckons.

‘It’s a real henhouse!’

In prisons, mental illness is spreading, but its care is lacking. In Roumieh, 7.5 percent of the prisoners are psychotic, 4.3 percent are bipolar, 41 percent are depressed, 34.4 percent are drug addicts and 4.9 percent suffer from post-traumatic stress disorders, according to the statistics given by the Justice and Mercy Association (AJEM), the only NGO present at all times in the country's 22 prisons.

Dany Khalaf, psychiatrist at AJEM, sums up the situation: “I’m the only psychiatrist here in Roumieh where, out of 3,500 prisoners, 300 experience psychological disorders. Each week, I visit a different unit of the prison. Roumieh is not the worst case. In the other 21 prisons of the country, there is no special psychiatric department”.

The Lebanese central prison is the only one in the whole country equipped with a psychiatric department, called "the Blue House". It was opened in 1994, and its facilities have never been brought up to standard. For the past few years, its living conditions have become frightening. ”It’s a real hen house,” says Raja Abinader, a judge in charge of prisons within the Ministry of Justice.

“The floor is covered with mould, the paint flakes off. Safety standards are not met, therefore fewer and fewer nurses and psychologists are willing to work in the prison now. It has become an inhuman place,” says the judge.

“The Blue House” is soon meant to be renovated through donations from an Italian cooperative and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). The 40 mentally ill prisoners of Roumieh prison are currently living in a mental and physical hell.

Nevertheless, according to judge Abinader, changing the law will not be enough. Some magistrates still need to change their mentalities on the matter. “Currently, a judge is supposed to appoint a psychiatrist who would visit the prisoners once a year in order to assess whether "they have healed yet". But mental illness is not curable. However, it can be stabilised through medication. Unfortunately, some judges refuse to appoint any specialist and have backwards views on mental illness.”

'Their theatre'

The curtain rises at the premiere of Johar… Up in the Air. The Blue House appears on the screen, which is also on the stage. A man is seen making coffee on a portable stove, another one is eating a sandwich while sitting down on the floor. Another one is telling his story to a prisoner sentenced to life who is going to play him. Since they cannot be on stage, prisoners from the Blue House have been sharing their personal story to the Unit A prisoners who are chanting them in front of the audience: “I am sorry Law, the sentences you’re rooting for are unfair, even before they are delivered. How can you accept them?” sings Fawzi, a prisoner with a high-pitched voice and the body of a gladiator.

By playing “mad” prisoners who are waiting to “be healed,” the ones sentenced to life have some perspective on their own fate. This is one of the main tools of this type of self-revelatory theatre. A therapeutic theatre whose purpose is to heal its actors, while creating a unique piece of art.

“You learn. I learned that nobody is allowed to take someone else’s life,” recites Youssef, convicted for murder and jailed in Roumieh for 25 years. The audience gives a round of applause.

Johar...Up in the Air also has an ethnographic approach, since all the prisoner's stories are directly linked to Lebanese political, social and cultural backgrounds, which helps increase the audience's awareness. Last but not least, along with the play comes a study about mental health within Lebanese prisons and a legislative proposal about the conditions of incarceration of mentally ill detainees.

Apart from wanting to stop using the words “madness” or “healing,” judges and lawyers have been working on a bill that pushes another type of verdict for mentally ill individuals: the inability to undergo their own trial. The play is, therefore, a good example of what Augusto Boal called legislative theatre.

However, Daccache prefers not to categorise the Roumieh Theatre. “I would rather call it their theatre, for after all, their plays are being shown within their walls, using their talent, their words, their audience and their message.”

This article was originally published on Middle East Eye's French website and translated by Nassima Demiche.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].