Andy Burnham calls for scrapping Prevent. Better late than never

The shadow home secretary, Andy Burnham, has joined the call to scrap Prevent, the UK's anti-radicalisation programme. Using a term previously cited by senior police officers regarding the government programme to tackle extremism, the senior Labour politician described Prevent as “toxic”.

Last month, the police chief tasked with heading and implementing Prevent, Simon Cole, said that government plans to target non-violent “extremists” through the introduction of more legislation risked the creation of a British “thought police”.

This mirrored the sentiments of Sir Peter Fahy, chief constable of Greater Manchester, who said that in seeking to fight extremism Britain could “drift towards a police state” where officers are turned into “thought police”. These fears are certainly not new and it is worrying that the government has failed to understand them. In 2007, the Archbishop of York, John Sentamu, one of Britain’s leading clergymen, warned that Britain was in danger of moving "close to a police state".

In a parliamentary discussion on Prevent, the minister for immigration and security, James Brokenshire, conceded that those who fail or refuse to implement the programme could face prosecution and imprisonment for terrorism offences. As such, these measures seem more in tune with Mubarak’s Egypt or Assad’s Syria than they do with Britain in 2016.

The effects of Prevent have clearly been felt hardest within the education sector and that is why the National Union of Students alongside various colleges and universities unions campaigned to boycott it. CAGE played a key role in the Preventing Prevent: Students Not Suspects nationwide tour, since we had some experience in how it works and had argued against it even before it became law after the Counter-Terrorism and Security Act (2015).

We believe these efforts have been effective and have had a significant impact in shaping the narrative against Prevent. Despite the barrage of media targeting CAGE and student activists as extremists and fanatics for seeking an end to Prevent - with our efforts described as a campaign to recruit an "army" of teachers, students and doctors to take on the government’s anti-extremism law - we are pleased to see our views becoming mainstream.

Burnham’s foray could have come sooner, but his voice has now been added to a growing number of important bodies like the National Union of Teachers, who overwhelmingly rejected Prevent during their 2016 annual conference, after saying that it causes “suspicion in the classroom and confusion in the staffroom” and calling for it to be scrapped.

Senior figures too, like former director of public prosecutions Ken McDonald, have expressed their views about the corrosive effects of Prevent on freedom of speech and research in universities by saying: “One is forced to contemplate a level of uncertainty that plainly risks a chilling effect on intellectual discourse and exchange, not to mention a deadening impact upon research into difficult contemporary questions."

The independent reviewer of terrorism legislation, David Anderson QC, recognising that Prevent is “sowing mistrust” in Muslim communities and is “a more significant source of grievance in affected communities than the police and ministerial powers that are exercised”, has called for a review of Prevent. While we welcome his submission, our view is that the outcome of any review must result in the abolition of Prevent. This undoubtedly is what Andy Burnham meant when he said Prevent is “so toxic” that “it’s got to go”.

In fact, speaking ahead of the 20th anniversary of the IRA bombing in Manchester's city centre, Burnham went further than most critics of the government: “The Prevent duty to report extremist behaviour is today’s equivalent of internment in Northern Ireland – a policy felt to be highly discriminatory against one section of the community.”

Echoing the views on the right to freedom of assembly in April of the UN special rapporteur, who said that Prevent “could end up promoting extremism” instead of tackling it, Burnham added: “Far from tackling extremism, it risks creating the very conditions for it to flourish,” and added: “The Prevent strategy and potentially this extremism bill are creating the conditions for more radicalisation not less.”

If Prevent is causing negative radicalisation, the law making it a legal duty must be repealed. Solutions to the problem have always existed elsewhere.

It can quite easily be argued that UK anti-terror laws in general have failed by necessity, since the threat level is equivalent to or higher than it was at the height of the Iraq war, when security services warned of resultant violence and increases in the likelihood of attacks. As such, Prevent cannot be seen in a vacuum, removed from other counter-terror laws passed over the years.

These have all in fact contributed to maintaining and even increasing the threat of political violence. There are really no “radical preachers” left in the UK and the last place to discuss controversial religious or political issues are mosques or Islamic centres. So why is the threat level still so high?

Ignoring push factors to radicalisation

The Prevent programme fails entirely in addressing the root cause of negative radicalisation by refusing to look at factors that marginalise and disempower target community actors. It looks only at the pull factors of attraction to organisations abroad, for example, but ignores the push factors that include alienation created by anti-Muslim rhetoric used by the media and politicians, as well as aggressive foreign and resultant domestic policies.

In Britain, the only long-term and tested way to tackle negative radicalisation that leads to violence is to learn from the Troubles of Northern Ireland.

According to Europol statistics collected in 2014, 99.3 percent of attacks in Europe were carried out by non-Muslims. Undue focus on 0.7 percent speaks more about prevailing attitudes than it does facts. Of course, the mass-casualty attacks in Paris and Brussels necessitate some kind of response and the security services already have more powers than ever before to deal with such threats.

However, when we consider that over 3,000 people were killed in the fight against the IRA, an end to violence only came about after the de-escalation of laws and rhetoric against Irish Republicans. This strategy, coupled with dialogue and attempts to tackle original grievances, which even included freeing of prisoners convicted of terrorism offences, culminated in the Good Friday Agreement in 1998 and an end to hostilities. Wholesale criminalisation of Republicans had bolstered the IRA - acceptance of their political voice diminished their need for armed resistance.

In seeking to enforce indefinable “British values”, politicians are undermining identities within the suspect communities and that is what the youth struggle with most. Britain of course is far better than France and Belgium in this regard and that is one reason why both examples, while clearly causes for alarm, do not rightly compare to the British Muslim experience. Paris, for example, has a history that includes the killings of hundreds of Algerians in the 1960s by French police. That is still in living memory.

The alternative to Prevent cannot be a revised "lite" version of it, since it is part of the problem. We know numerous people who have, for example, been persuaded not to join organisations like the Islamic State group after speaking with former prisoners, returned “foreign fighters” and Islamic scholars.

These stories are not trumpeted, ironically, because of the very fear these advisers have of being labelled extremists and terrorists. Muslim communities and individuals have been working hard to root out elements that wish to bring harm to this country and that process must be allowed to develop and succeed unhindered by draconian interventions like Prevent.

- Moazzam Begg is a former Guantanamo Bay detainee and currently the director of outreach for UK-based campaigning organisation CAGE.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

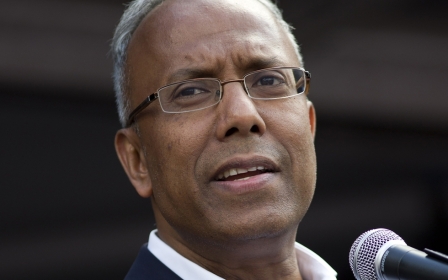

Photo: Britain's Labour Party Shadow Home Secretary, Andy Burnham, addresses delegates on the final day of the annual Labour party conference in Brighton, UK on 30 September, 2015 (AFP).

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].