The children are in danger: Welcome to 'the kids' Guantanamo' of Egypt

"Do you know what it's like to be one of the reasons someone is behind bars?"

With those words, an Egyptian lawyer greets me as he tells me about his latest case. Mohamed Abdelsayed, a 14-year-old boy, was charged with protesting and the possession of explosives after a taxi driver drove him to a police station and turned him in on suspicion of protesting. He remained detained for a month, and was released while his case was transferred to court. Mohamed, under no illusion regarding the legal system, was wary of attending the hearing, but was convinced by the lawyer otherwise, only to find himself sentenced to five years.

Such is the reality of Egypt's youth today. Whilst Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi maintains that the youth are Egypt's hope and future, actions speak otherwise and a lot more loudly at that. As Sisi begins to mark his two-year anniversary since officially becoming president, Egypt’s list of achievements is rich with empty promises and broken spirits.

While the Egyptian state media fawned over the self-appointed field marshal during his presidential campaign, Sisi remained tight-fisted with his promises, offering nothing tangible that he could be pinned down on other than vague answers strangely reminiscent of America’s Donald Trump, such as that Egypt will be great again.

When hard pressed over questions about the economy, he sternly asked citizens to be more frugal and "tighten their belts". Later, when questioned about the arbitrary detentions, Sisi admits that perhaps some have been wrongly jailed in Egypt’s enthusiastic crackdown on the opposition, but promised to release them.

Two years on, Egypt’s statistics for detainees continue to rise to mind-boggling levels, with a conservative estimate of 50,000 political prisoners. “We’re living the impossible, the unthinkable,” the parent of 15-year-old Mohamed Imad tells me.

Electrocuted, whipped, beaten on his face, jumped on his back; the list of horrors is unending as his father fights to keep tears out of his voice. “My son was born in Japan you know, I wrote to the Japanese ambassador, if [sending him to Japan] is what it takes to keep him safe, I’ll give him up. Japan can take him as one of their own – the children here are in danger.”

Held for over for two years on 10 counts, ranging from protesting to charges of murder, Mohamed has yet to be sentenced. “All my son will know from this country is its dungeons. He’s seen more than what any 15-year-old should see.”

Taken from their homes in the early morning, picked up from schools after finishing exams, turning up dead, in prison – or in some cases, not turning up at all - the victims of the Egyptian government’s relentless campaign against dissent has spiralled into unchartered waters with children being the target.

When Hisham Naser chanced upon three girls being beaten up by thugs on the street over suspicions that they were protesting, he tried to get them to stop. The neighbours, instead of helping him, called the police and turned him in. In the police station, he was welcomed with beatings and detained for months, before being sent to Kom el-Dikka, and later the notorious detention centre Al-Aqabiya, which the children and their families have taken to calling "the kids’ Guantanamo".

“They promised us our children wouldn’t be sent back there. Countless human rights groups and lawyers promised us the children won’t have to go back to that Guantanamo. But they took them back there,” Hisham’s mother tells me sadly.

When the children found out that they were being sent back to Al-Aqabiya, they refused to move. Thrown face forward onto the ground, officers pounded their backs and stomped on their heads with their boots. An officer jumped on Hisham’s arm and left it broken, unable to move it for six months, and denied medical care. The aggravation of his health led to a few fits, and the prison guards’ response to these attacks was to promptly throw boiling water at him.

“I visited him after three days, and I didn’t recognise him anymore,” said his mother.

He was forced to lie on the floor and mop up his blood with his own body, to remain for hours on end perched at the tip of his toes and beaten if he dared move. Officers rely on those brought in on criminal charges to beat and torture the political prisoners.

“It’s true,” the lawyer confirmed. “Whatever the families tell you is only a small part of what actually happens there.” Rife with rape, torture and beatings to death, life holds no meaning anymore to the children in Al-Aqabiya, leading to mass suicide attempts.

The stories of ill-treatment don’t end there: each one is more horrific than the other. Young girls are told by military officers that as bullets, gas and arrests didn’t work, the only way to break them will be to make sure they leave pregnant. Upon arrest – and after invasive pregnancy tests - officers jibe and let the girls know that tonight they will spend the night in their underwear, leaving them awake all hours.

From the forced disappearance of 12-year-old Anas Badwy, who spent a year in Alazooly Prison before anyone knew anything about him, to Isam Aldin, a 15-year-old with a chest condition picked up from the street and hospitalised four times since his arrest, there are countless stories coming out daily, painting a bleak picture of Egypt’s lost childhood. But as one father said, it is the deafening silence of the world that is giving the regime carte blanche to abuse and continue robbing children of their safety and life.

“My son is one of hundreds. Before you had an excuse; you didn’t know. But now, now you know.”

-Noor El-Terk is a keen advocate for social justice with a particular interest in the MENA region. She holds a masters in Chemical Engineering at other times and Tweets at @kelo3adi

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

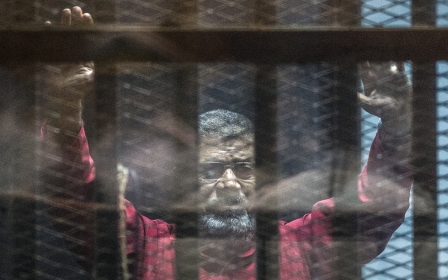

Image: A member of the Egyptian security stands guard outside the police academy in the capital, Cairo, on 21 April 2015 (AFP).

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].