Award-winning Syrian husband and wife fight for freedom

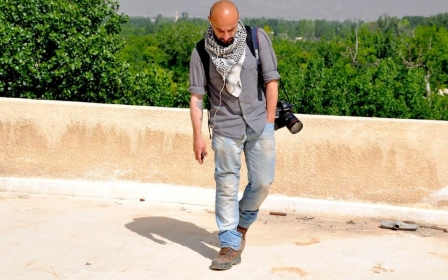

LONDON - Sipping coffee at a table outside a London pub, Mazen Darwish and Yara Bader hardly look much like high profile dissidents. Yet the Syrian couple are amongst the most well known activists campaigning for human rights in their home country. They settled in Berlin after being forced into exile several months ago and now travel the world recounting their experiences and demanding justice for the Syrian population.

“It is because I know how much people are suffering that I feel I have a double responsibility now to do what I am doing,” Darwish tells Middle East Eye.

He became a prominent media activist for his work at the Syrian Centre for Media and Freedom of Expression (SCMFE), which he founded in Damascus in 2004.

The organisation documented and published news on violations of freedom of speech under Bashar al-Assad’s government. This work raised international attention and the centre was recognised as a consultative organisation by the UN in 2011.

When the revolution broke out in March 2011, Darwish covered the clashes between civilians and government forces in Daraa that developed into civil war. He was arrested in February 2012 and later charged with “publicising terrorist acts”.

This was not his first time in jail. Neither was it the first closure imposed on the centre's headquarters. In fact, he met his future wife Bader two days after the offices were raided by the security agencies for the second time, in September 2009. A mutual friend introduced them at a café frequently visited by “troublemakers,” as she puts it. “I was completely impressed. He was still full of hope and energy and was already planning how to do things again.”

A few days later he suggested they collaborate together on a report about censorship and monitoring of culture in Syria. “We wrote a 20-page report that was on Mazen’s table for final review before publishing when it was confiscated along with the computers and everything else when we were arrested. I will always be very sad about this,” she says.

Dangerous country for journalists

As a culture journalist, Bader used to review exhibitions, films, plays and books. “Nothing is dangerous until you cross the red lines, for which you don’t have a guide book. Even talking about sports can cause you trouble,” she says. But in a country ruled under a state of emergency for 43 years, “people have learnt to develop their own [methods of] supervision which control their thoughts even before they write.” She recalls the Disney film The Lion King as an unlikely example of censurable material. Why was it banned from cinemas? She cannot help but the clue could be in the name of the ruling family - "lion" in Arabic. She gives a wry smile as she explains: “The king is portrayed as a lion and his brother kills him to seize power.”

Aggression against local and foreign journalists has been committed by all groups involved in the fighting. Reporters Without Borders ranks Syria as the fourth most dangerous country in the world for media workers after Eritrea, North Korea and Turkmenistan. With barely any professionals on the ground, citizen journalists shoulder the burden for reporting on what is happening around them. But these independent voices, claims Darwish, are barely heard because digital outlets or television channels “don’t accept their stories”. Every party wants to tell their own version of the story.

Bader’s husband opposed censorship from any side with firm determination and on his sixth and last arrest he disappeared for 10 long months in which he was tortured and put in solitary confinement, before being transferred to Damascus central prison, Adra.

A voice for the detainees

As dark as it sounds, Yara confesses she did not lose hope at that time. It was after two years of hardship and uncertainties and following President Assad’s amnesty for opponents in 2014, when his release was rejected in a last-minute decision and he was moved yet again to another security branch that she broke down. “I started to think that our dream would never come true… Security branches are the worst in Syria, many people die in them. I fell apart and stayed in bed for more than two weeks. I couldn’t do anything else…” Even today she doesn’t think she has completely recovered from this.

It took another year until Darwish could finally walk free from prison in August 2015. During those three and a half years, Bader, who was also briefly detained, became the acting director of SCMFE and campaigned in Syria and abroad for the release of her husband and other detainees jailed for defending the right to free speech. She received several international awards, such as the Human Rights Watch Alison des Forges Award for Extraordinary Activism. While in prison, Darwish was also awarded a prize. Salman Rushdie chose him to share the PEN Pinter Prize for International Writer of Courage.

'There is no meaning to life without human rights'

His acceptance speech was a testament to his bravery, defiantly critical of both the government in power and Islamic State (IS). But it also exuded optimism about the future and the same commitment to the values of freedom and dignity that put him in prison. “My father was detained for 17 years, my mother for one year, other relatives were jailed too. When you are born in such a family and you live in a country like Syria, these values are the most important thing. There is no meaning to life without human rights and democracy,” he tells MEE.

This commitment is what kept him alive throughout his ordeal. “Without beliefs and hope there is no way to survive. In the last 20 years I have been jailed many times, but I believe in what I am doing. If I lose my values I would lose myself,” Darwish says. He still struggles with his English, for which he apologises profusely, and is shy and gentle mannered, but none of this undermines his sense of purpose.

Once out of prison, he was shocked by the state he found his country in even though his wife had given him discreet hints about the situation during her supervised visits. “For the first four months I didn’t give any interviews. I needed time to fill the gap. I read a lot and spoke to many people from different levels” to comprehend the scale of what had become a civil, regional and international war.

He says the government in Damascus repeatedly tried to get him to collaborate with them. He refused and the threats started again. “They said my case was not closed yet and my judgment was still pending… This time I thought it was very easy for them to kill Syrians and nobody would be held responsible for it.” After two tense months Darwish and Bader fled their homeland.

Shifting the focus of the peace talks

Darwish has made no secret of his frustration with the hesitant response from the West to the Syrian war. “It is very dangerous,” he warns. “The governments want to deal with the results and not with the reasons. This way extremism and the refugee crisis will continue. Giving money to Turkey (referring to the EU-Turkey deal) might solve the problem for two or three years but the political situation in Turkey could change at any time, as is happening now, and we will be faced with thousands of refugees coming to Europe again,” he concludes.

For him, the concept of “transitional justice,” based on accountability for war crimes, rehabilitation of trust in the legal system and reparation for the victims, should be square on the negotiating table. “It is not about revenge but about protecting society from revenge. If people from any party don’t feel satisfied with the justice done, they will start another civil war and it will perhaps be worse than this one,” he argues passionately. The process, he says, “needs to be in Syrian hands because there are many different sensibilities in Syria.” In his view, that is the only way to reach reconciliation.

The new British face in the peace talks, UK Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson, does not fill Darwish with hope. Although cautious until he sees what Johnson has to offer, Darwish’s concern is that “they [will] make the same mistake they did in Iraq in 2006 and 2008: military action, bombing al-Qaeda and killing al-Zarqawi, without a real political strategy. Supporting the sectarian dictatorship of al-Maliki has led to IS, which in comparison, makes al-Qaeda look almost liberal,” he quips. “I’m afraid this might be Mr Johnson’s way of solving the terrorism problem.”

Darwish is not against military intervention. He thinks it is possible to defeat extremists in Syria but it requires a sort of Marshall Plan, "a military, economic, political and social plan for Syria, in which Syrians get to choose their leader; someone who shares their values of freedom and democracy, not a dictator. Dictatorship and terrorism live together, they need each other in order to continue.”

The long journey to recovery

With the conflict in its sixth year, the latest grim figure of 400,000 deaths, medical facilities destroyed and the peace talks stalled, formulating post-conflict strategies might seem slightly premature. However, Darwish is looking to the future.

“The values of the revolution are still alive now in Syria, young people believe in dignity, freedom, equality… When the war stops, the Syrian people will be able to solve all this. It will take a long time, perhaps 30, 40 or 50 years, but we know from history that all nations that move from dictatorship to democracy pay a heavy price. The problem is that if the war continues, perhaps the Syria we know now won’t exist in the future.”

Darwish and Bader only have minutes to share a cigarette before their talk at the Free Word Centre starts. Tomorrow they go back to Germany, which they now call home. Until the brutal suffering of civilians ceases and they can return to their homeland, they will continue to fight for their dream for a better Syria.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].