Dutch Islamic groups resist becoming informers in surveillance drive

ROTTERDAM, Netherlands - Marianne Vorthoren sits in her bright sunlit office, sharing a plate of biscuits made by a local woman for a community forum the night before. She is open, and quick to smile – but she is also cautious. “We are not the Muslim intelligence agency,” she asserts.

“Of course we feel a shared responsibility to protect our youngsters. But I am very strict. We don't want to be involved in reporting people for acting suspiciously. That's up to the authorities."

Vorthoren finds herself in a difficult position. A convert to Islam, she now directs the Platform for Islamic Organisations in Rijnmond (SPIOR), based in the Dutch city port of Rotterdam. It is a prestigious role that she is passionate about – but as she attempts to strengthen the organisation’s community work, the Dutch government is demanding Muslim leaders provide more information about that community.

The Netherlands has been praised across Europe for anti-radicalisation strategies which emphasise community dialogue. Aimed mainly at the country's Muslim minority (around four percent of the population), their focus has been on local initiatives implemented by municipalities, rather than those handed down from national government.

For several months, top intelligence officials from 30 European countries have secretly met every week in the Netherlands to share information on suspects, including children as young as nine.

Following recent bloodshed on European soil, security agencies are under pressure both to foil attacks before they occur and to halt the murky process that comes before, known as “radicalisation”.

Amid warnings about further attacks and a spike in far-right support across Europe, some - like Vorthoren - fear that the Dutch government wants to co-opt community leaders, thereby alienating already marginalised groups.

“The essential ingredient is trust within communities. If you also have a reputation for seeking out potential suspects, that will be impossible,” said Vorthoren.

She listed the challenges for trust-building: laws that allow dual nationals to be stripped of Dutch citizenship if they are suspected of planning to join groups like Islamic State or al-Qaeda - even if they have not been convicted of any crime by a court; the threat of losing a passport to prevent travel; even the risk of having their children taken away.

“This makes it complex,” said Vorthoren, “because people fear that if they report [worrying behaviour], their loved one's children will be taken away. We have told the government this, but there is tension. There is always tension between prevention and repression – that's why organisations have to be very clear about their role.”

Vorthoren said that she understood that sometimes strict measures have to be put in place. “It's just a question of how they are implemented.”

Preventing 'a kind of Detroit'

Less than a two-hour train ride from the Belgian capital Brussels, which teems with heavily-armed police, an atmosphere of calm prevails in Amsterdam. Half an hour south, the cosmopolitan port city of Rotterdam maintains the same aura of muted bustle, with barely a law enforcement official to be seen.

It is the most international city in the Netherlands, with nearly half its population born outside the country and nationals from at least 170 different states.

But it is a city that also comes with inequality built in: most housing projects south of the River Maas, just across the water from Rotterdam's financial north, were built to house migrant workers for the port. Districts in the south still bear the names of former Dutch colonies.

Cramped conditions in the city's south led to race riots in the 1970s, primarily between Dutch citizens and immigrants from Morocco and Turkey, two of the largest non-Dutch communities.

Since then, authorities have fought to keep Rotterdam's south side, where the number of families relying on state benefits is double the average, from becoming “a kind of Detroit,” as one social housing official described it recently.

Mayor Ahmed Aboutaleb, the first Muslim mayor of a major European city, has won near-universal praise since taking on the job in 2009 for projects focusing on community inclusion.

Famous for telling Dutch extremists who “turn against freedom” to “f*** off” after last year's Charlie Hebdo attacks, Aboutaleb usually prefers a more nuanced approach. Under his stewardship, municipal employees meet citizens at fortnightly forums, small businesses are required to set aside jobs for local people and co-operative kitchens have appeared in areas which many had consigned to the scrapheap.

Cohesion projects at risk

But life is far from untroubled – and members of Rotterdam’s 100,000-strong Muslim community tell Middle East Eye that cohesion projects risk being sabotaged by increasingly intrusive information-gathering within those groups. Division and discrimination, they say, are on the rise.

According to Bart Schuurman, a researcher at Leiden University's Centre for Terrorism and Counter-terrorism, the situation has changed since changes were brought in by central government in late 2015.

“Radicalisation is a hot topic for many government agencies,” he told MEE, “and there is now more co-ordination between them.

“The police, the municipalities, the secret services and community leaders might all get together to discuss certain individuals. A community leader might then visit the family [of an individual that authorities are concerned about].

“This is often done in a pre-criminal phase – it may not be somebody who is directly involved [in criminal activity], but an individual who has said something that is a cause for concern at school, for example.”

The 'Young Imam'

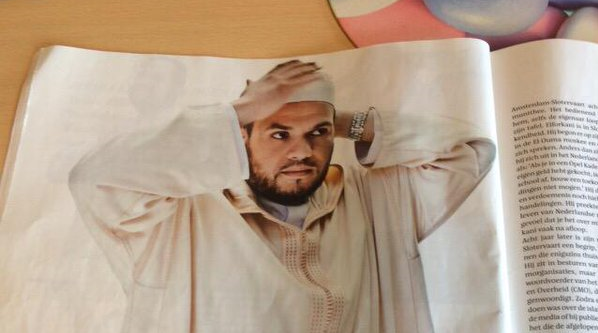

One key backer of this new integrated and more intrusive approach is Yassin Elforkani, 34, a preacher and until last year head of the CMO, the statutory body that oversees the running of more than 380 mosques in the Netherlands. Elforkani has urged the government to strengthen its counter-terror strategies, and warned earlier this year that an attack would hit Amsterdam within six months, telling the Danish press that “the terrorist networks are ready”.

“Many people in the communities know about terrorist networks but choose to keep their mouths shut to protect young people,” says the 34-year-old dubbed the “Young Imam” by sympathetic newspapers and seen by many as the fresh face of moderate Islam in the Netherlands.

Though Elforkani is an opponent of political Islam in all its forms, he did publicly oppose the government's 2014 plan, later shelved, to ban all organisations with a link to a loosely defined Salafism. However, many of the young imam’s other outspoken statements have made him a controversial figure within the communities he represented as head of the CMO.

One young Muslim, who asked to be identified only as Farid, told MEE that Elforkani is seen as a “collaborator” by many after insisting that Islam has a problem, and must reform in the face of the rise groups like Islamic State. Elforkani stepped down as head of the CMO last June after reportedly receiving threats.

Yet at a community forum in Rotterdam one year on, Elforkani cuts a charismatic and confident figure, his energy seemingly undampened by recent challenges.

Wearing a sharp suit, he strides around the hall at Essalam Mosque, one of the biggest in Western Europe and certainly the largest in the Netherlands. The centre, which has goalposts in the courtyard and hosts diabetes screenings and legal advice surgeries along with the usual prayer services, is holding a debate on “Alienation and Religiosity.”

Elforkani is chairing the event and thunders to an assembled audience of local residents: "We need more positive role models of Islam.

Reaching out to Muslim converts

Stefanie Danopoulos, the only woman in the Netherlands to chair a mosque, runs the Middenweg Centre. “The government likes Yassin Elforkani,” she tells MEE, “because he is educated and speaks about moderate Islam.”

The centre, whose name translates as “Middle Way” in English, is in a modern church conversion in the centre of Rotterdam, with clean lines and the old stained-glass window still intact. During Ramadan, Muslims and non-Muslims gather each evening to break the fast together. Middenweg focuses on reaching out to converts to Islam, who Danopoulos says often find themselves isolated from their families and mainstream society.

Converts are also an area of focus for government agencies attempting to stamp out forms of Islam seen as unacceptable. Research shows that converts are generally over-represented among people who have travelled from western Europe to fight in Iraq or Syria: for the Netherlands, up to 18 percent of the 230 people who have gone abroad to fight are thought to be converts, even though converts account for less than two percent of the Dutch Muslim population.

As a result, the government has made converts one of six target groups for a national anti-radicalisation strategy that is currently out to tender for Muslim-led organisations.

Some of Danopoulos’s volunteers have been called in for training by Rotterdam security officials. “There will be training on what we might see, what to do when we see it,” she said. “I told them that this is what we're already doing. I told them: ‘We are doing your work.’

“They laughed.”

'They can make you but they can break you'

Fostering dialogue is becoming ever more difficult thanks to new restrictions on preachers visiting the country to speak.

Essalam Mosque faced controversy last October when it invited Egyptian preacher-born Fadil Soliman to give a talk. The discussion was titled “The IS delusion”: Soliman described being spat at and having a chair thrown at him by a fellow Muslim for saying that 9/11 was unjustifiable within Islam. But much local media coverage overlooked the topic of the talk, instead branding Soliman a “hate sheikh” with ties to the Muslim Brotherhood and a penchant for chopping off hands.

“Of course Soliman is against IS,” said Danopoulos, “and it's good for young people to hear that from him. But they called him a hate imam.

“Now you have to ask for a form and get permission to invite [a preacher from abroad]. It takes six weeks and they check how much people earn. They are making it very difficult – and in the end they can still just say that the preacher cannot come."

Danopoulos says the atmosphere has become so tense that the Middenweg Centre, along with other mosques and religious centres, makes audio recordings of everything that goes on, in case anyone disputes what has been said by preachers or participants.

The centre, originally bought and renovated with funding from Qatar, now runs solely on funding from users. Danopoulos says it is possible for projects working with the Muslim community to get government money, but it is a risky venture.

“They have to know everything. And that’s exactly what I don’t want - they can make you but they can break you too. It's risky to be dependent, especially at the moment.

“I just don't understand why they are doing this,” said Danopoulos, shaking her head. “They will create a very big gulf between Muslims and non-Muslims. If the government behaves like this, it only furthers divisions. Our idea is to come together.”

Injustice and Islamphobia

For Vorthoren, the increasingly divisive atmosphere is making it near impossible to carry out the real community work she sees as key to tackling the root causes of alienation and extremism. In the shadow of the government’s single-minded focus on its anti-radicalisation agenda, she says, projects like a community garden outside the Essalam Mosque – which brings together local residents and young children – are finding it difficult to attract attention.

“Prevention doesn’t just mean telling people that killing others is wrong. It’s about abstract things: it also means addressing injustice and a sense of injustice.

“Young people we speak to are very quick to say that what Islamic State is doing is wrong. The thing that is most talked about, though, is injustice within this society - Islamophobia is a really big issue,” she said.

She pointed to a report published by SPIOR in May that found that, though reported incidents of discrimination in the region had fallen 25 percent since the start of 2015, the number of incidents targeting Muslims and particularly Muslim women, had doubled.

“If you don't address that injustice adequately, that feeling can be abused by extremists as a recruiting tool. It's about a sense of belonging.

“When people say there is an easy answer to this issue, I just don't trust them."

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].