Whether we get Clinton or Trump, Iran nuclear deal is headed for trouble

Since an angry group of young Islamic revolutionaries overran the United States embassy in Tehran in 1979, the US has used every foreign policy tool, including covert operations, to tame Iran’s perceived hostile foreign policy.

Among these tools, sanctions have played a major role. Indeed, sanctions stood out among other tools at the Americans’ disposal in bringing the crisis over Iran’s nuclear programme to an end.

But the Iran nuclear deal, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), has created a significant, but sparsely noted dilemma for the US.

As long as the implementation of the deal is in progress, the Americans’ hands are tied simply because the imposition of any new effective sanctions would most likely violate the deal and would lead to its collapse.

The sanctions that the US imposed in reaction to Iran’s March missile test were indeed more symbolic and were not in violation of the deal.

New sanctions, no deal

Following the conclusion of the deal, Iran’s leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei instructed Iranian President Hassan Rouhani that the agreement would be rendered void if any future sanctions, under any pretext, were imposed on Iran in the next eight years.

The instruction was understandable. Iran can only maintain a shadow of its nuclear programme, and if it accepts new sanctions adopted against it under different guises, the purpose of agreeing to the deal would be completely negated.

As of today, the most contentious points between Iran and the US are Iran’s missile programme and its unwavering support of Hezbollah of Lebanon.

If the hardliners in Tehran do not make political waves beyond their typical rhetoric that would provoke the US, its Congress in particular, to act, it seems unlikely that a future US administration would initiate a step to jeopardise the deal.

This is primarily because the deal is not only a bilateral agreement between Iran and the US. It is also an international agreement endorsed by the UN Security Council of which the US, of course, is a member.

The last thing the chaotic Middle East needs is a new crisis between Iran and the US, but the question is whether the current situation is sustainable over the next several years.

Expanding missile programme

As a result of a culmination of sanctions and cancelled contracts since the 1980s, Iran has been left without an effective air force, yet it has been unable to purchase jet fighters and bombers.

Meanwhile, its regional adversaries – including Israel and Saudi Arabia – enjoy considerable fleets.

Consequently, Iran will continue the expansion of its missile programme now at the heart of its defence doctrine, something the Obama administration is also firmly against.

To underscore the significance of the missile programme to Iran, Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif, in a tweet in March, contended that Saddam Hussein would not have dared attack Iran if Iran had had missiles.

Destructive dreaming

In Iran, there is a politically powerful current that does not shy away from any opportunity to try to reverse the current situation to the pre-deal era and any chance to embrace hostile relations with the West, particularly the US.

By day, opponents to the agreement angrily and relentlessly attack the pact and, by night, they dream of the deal’s collapse.

“The [JCPOA] is by no means an honourable document for the Iranian people,” Major General Mohammad Ali Jafari, the commander of the Islamic Revolution Guards Corps (IRGC), said recently. This faction fiercely criticise Rouhani and his team over accepting what they call “the humiliating nuclear agreement”.

Iran’s supreme leader also does not miss an opportunity to discredit the deal in his speeches. Alluding to the reluctance of European banks to work with Iran, he recently argued that the Americans have breached the nuclear agreement and have “constantly create[d] obstacles in the economic relations between Iran and the other countries”.

Further provocation

Adding to the already tense situation, the Iranian hardliners have used the missile programme for their own provocations. For example, the long-range ballistic missiles, which are capable of reaching Israel, that Iran tested in March, were marked with a statement in Hebrew that read “Israel must be wiped off the Earth.”

Having hostile relations with Israel is one thing, but what could that open provocation have been aimed at?

On another front, US and Israeli allegations that Iran supports terrorism, namely Hezbollah, can escalate the Iran-US conflict at any given moment.

In the 1980s, the Hezbollah militia emerged in Lebanon. It was funded by Iran, and its forces were trained and organised by the Iranian Revolutionary Guards. Iran sought to change the balance of power in favour of the minority Shia in Lebanon and to utilise Hezbollah as a proxy force that would threaten the security of Israel in the context of a deterrence doctrine.

On 24 June, the Hezbollah chief brushed off fresh US sanctions, and in an unprecedented open statement said: “As long as Iran has money, we have money. ... Just as we receive the rockets that we use to threaten Israel.”

Against this backdrop, the hawks in the US establishment, particularly in the Congress, and the Israeli lobby are waiting impatiently for an opportunity to impose new sanctions on Iran knowing that it would undoubtedly lead to the deal’s undoing.

In July, Obama “made it clear that he will veto any legislation that prevents the successful implementation of the JCPOA”. However, things may change in the future.

What next?

Answers to the following questions may gauge the likelihood of the deal’s collapse.

If the next president is Hillary Clinton, the favourite candidate of the Israelis, and the Congress remains Republican-dominated after the November elections, will Clinton be prepared to fight with Congress over Iran were Iran to display its missile abilities and accomplishments?

How long can she resist Israel’s pressure and its lobby before confronting Iran’s support for Hezbollah?

But if Trump is elected, could he stop himself from cooperating with the Congress to impose new sanctions on Iran if it falls again into the hands of the Republicans?

What if Democrats regain control of Congress - which is possible, at least in the case of the Senate? In the absence of Obama in the White House to fight tooth and nail for the deal, would Congress be able to enforce sanctions against Iran, considering the activities of those in Tehran who deliberately seek to escalate tension with the US?

Realistic answers to these questions leads one to conclude that fallout from the deal, in the next eight years, is a real possibility.

- Shahir Shahidsaless is an Iranian-Canadian political analyst and freelance journalist writing about Iranian domestic and foreign affairs, the Middle East, and the US foreign policy in the region. He is the co-author of Iran and the United States: An Insider’s View on the Failed Past and the Road to Peace. He is a contributor to several websites with focus on the Middle East as well as the Huffington Post. He also regularly writes for BBC Persian. He tweets @SShahisaless.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

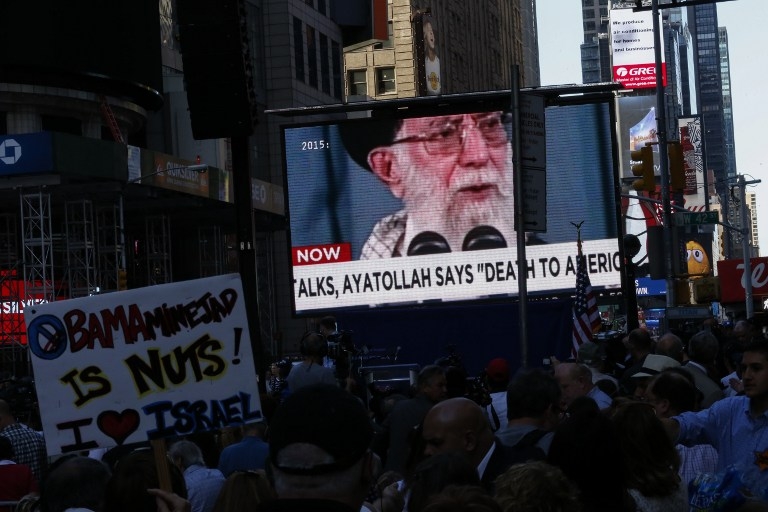

Photo: Ayatollah Ali Khameini is projected on a screen during a rally against the nuclear deal with Iran in New York's Times Square in July 2015 (AFP)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].