Remembering Rabaa: A survivor's story

It was 6am, 17 percent power remaining in my phone battery and I couldn't sleep. Within the next hour, I would be making what could have been my last phone call to my brother, before witnessing what was later called the “worst single-day killing of protesters in modern history".

The first signs

The date was Wednesday 14 August 2013 and I was two months into my annual holiday to Egypt. My friends and I had watched the military coup unfold on TV screens just a month earlier. We joined the sit-in in Rabaa Square to add our voices to the thousands of people gathered there who were asking for their democratic rights to be respected.

That morning, I left my friends Amr and Salim sleeping in our tent and headed for a local cafe near Tiba Mall which had become our daily hang-out during the sit-in. There, I bumped into another friend, Mohamed, who was fiddling with his camera. He lived locally, so he usually went home every night, but on this particular night he had decided to stay.

As the sun rose on the 47th day of the sit-in, I quickly noticed that something felt odd.

Across the road from where I sat, a 13-storey building that belonged to the military had just completed adding a new heavy duty fence, protecting it from top to bottom. I found this quite strange, considering that no one had tried to attack the building during the sit-in.

The second thing I noticed was that on the roof of the building some new sand bags had appeared, positioned every few metres apart, facing me.

My battery was running low. It was only when I tried to plug my phone into the usual socket that I would use and saw that the electricity had been cut that I realised something was definitely happening, and my low battery became a minimal concern.

I returned to the cafe, looking at the rooftop and the protesters' tents stationed below, when a man appeared on the roof and pointed a rifle towards the protesters, then he quickly hid. “Did you see that too?” the cafe owner asked me, flabbergasted. It was then that I knew what was happening. I started tweeting about it.

It was about 6.30am by this point. I left the cafe and decided to check out what was happening on the back roads, behind Tiba Mall on Anwar Al-Mofti Street. The roads were empty, nothing looked out of place.

On my way back, I noticed a man and a child start pointing in the direction behind me. I turned to look and my heart dropped.

It had started.

Panic in the air, frantic phone calls

A police Humvee quietly appeared from a side road, mostly hidden from view by the sand bags protesters had stacked at the entrance/exit to protect the sit-in. I’d never seen the police use a vehicle like that before, and it was less than 20 metres away from me.

My thoughts were all over the place, my mind went into overdrive, until one thought became clear: run Mahmoud.

As I turned and started to run, the first tear gas canister was fired and fell a few metres from me.

By the time I got back to the tent, everyone was awake. There was panic in the air. Frantic phone calls were being made to wake up relatives and friends to give them the news.

Snipers and security forces appeared on the roof top of the military building opposite and started shooting. At this point our emotions stopped and our survival instincts kicked in. People were running frantically as tear gas rained down on us. It was chaos.

My friends and I paused for a brief moment to gather our thoughts. We covered our faces to prevent breathing in the tear gas. Our online activism during the days of the 25 January revolution had taught us that to defuse a gas canister we should put it in a bucket of water of some sort. Along with other protesters, we started to gather anything that could be used as a bucket and filled them up from a tap at a nearby cafe.

Running back, I realised that I was in plain sight of a line of snipers on the rooftop opposite

The area started to clear as people sought cover and attempted to get away from the tear gas. Suddenly, a protester standing a few metres from me fell to the ground, motionless. There was no time to check what had happened to him: We picked him up and carried him to El-Nasr, the main road, where we found people on motorbikes who were carrying injured protesters to the field hospital.

This was something that had been done during previous massacres in Rabaa. Running back, I realised that I was in plain sight of a line of snipers on the rooftop opposite.

Back in the side roads, we continued placing tear gas canisters into the water buckets. The gunfire intensified. They were now shooting into the side roads. We could hear gunshots coming from the back road Anwar Al Mofti Street. It was a crossfire. Bullets were ricocheting off buildings just metres from us. We found cover in an alleyway near the mall. We were stuck and surrounded.

We soon realised our alley had an entrance easily accessible by the security forces.

We needed to leave as soon as possible, and the only way out was to run out through the open, in front of the snipers.

At that point, with the last bar of power in my phone battery, I made what I thought would be my last phone call. “It started,” I told my older brother, who was in Alexandria at the time. He was half-asleep and didn’t understand what I was saying. “Switch on the TV!” I told him.

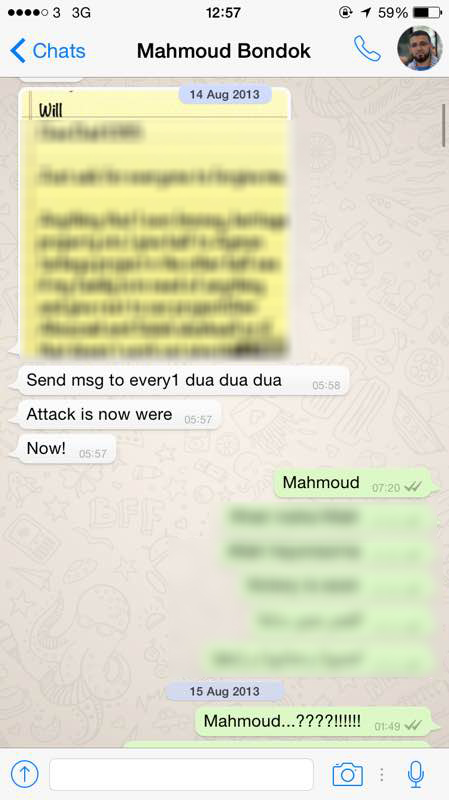

I hung up and tried to call my close friend in London. No answer. I sent him a screenshot of my will on WhatsApp, including a list of my debts and a message to my friends and family. I had started writing it after the first massacre I witnessed in the square. I hurriedly finished it off and sent it.

Time was running out and there was only one way to safety. Without a safe path to leave, we were forced deeper into the sit-in.

Threat from snipers

We sought refuge under a staircase that hid us from view from the snipers on the rooftop. There were other protesters gathered there too. A young man standing near us stepped into the pathway in front of us momentarily to have a look at what was happening. He fell to the ground instantly.

We instinctively leapt forwards and grabbed him. We noticed he had been shot in the neck. Blood was pouring everywhere. The bullet had taken off a chunk of his neck but he was still alive.

Our priority was keeping him and the other injured protesters who were with us alive. Someone used a T-shirt to make a make-shift bandage and put pressure on the wound.

We had to move fast to get the injured man out. He was carried by a group of protesters, including Salim. They waited for the gunfire to stop to make the run.

“Now!” one of them shouted and they ran across the pathway and made it to the other side. Next, along with Amr, it was our turn.

I couldn’t think about not making it across - my mind wouldn’t even let me. Without exchanging words, we took deep breaths and ran. And we made it.

As I was running away from the crossfire, my chest suddenly became tight and I fell to the floor. I couldn’t breathe. I started to cough up blood. The tear gas had filled my lungs, but we weren’t safe yet.

“I don’t think I can move,” I told Amr. “I can’t breathe.”

“We can’t stay here, we need to go,” he said.

He lifted my head against the wall, and put his inhaler in my mouth and said “breathe”. After two puffs, my chest felt much clearer. I could breathe again. “Let’s go,” I said.

We headed towards the hospital in the centre of the sit-in that could be reached by one of two routes.

When we approached the first route, an alleyway, a masked security officer wearing all black and holding a gun turned into the alley from a side road a few metres ahead of us. We made eye contact for a moment, before he turned back into the side road and disappeared from view.

We instantly turned around and legged it towards the parallel pathway, the second route.

As we entered the pathway, a group of protesters on the pathway were running towards us. “Go back,” they yelled. “They [security forces] have arrived. Go back!”. We were surrounded and trapped.

Non-stop gun shots

We ran to a block of flats and tried to open the door to seek shelter. The door was locked. It was at this point that the thought I had been blocking from my mind the past couple hours could no longer be avoided. This was it. Death or detention.

We sat down, resigned, behind a makeshift shelter alongside other protesters, waiting for the inevitable.

I checked my pockets and was relieved to find that I had remembered to keep my passport with me, so that if anything happened they would be able to identify me. My phone battery had died and we still didn’t know where Salim was.

Suddenly, the door to the block of flats opposite us swung open. “Come in,” shouted a man.

We all ran towards him, inside we found tens of other protesters, some injured, seeking refuge. It still wasn’t safe and we needed to keep moving. We ran up the stairs silently. On the fifth floor, we found an empty storage room, about two metres square in size, and six of us crammed ourselves inside and closed the door.

There were no lights, there was no phone reception and only one tiny window. We could hear non-stop gun shots from the roads outside. Alarms were ringing. We could hear a helicopter flying low above the square, and the noise from the microphone on the centre stage. We all knew that at any moment security forces could find and kill us all. We didn’t exchange any words for fear of being heard and found.

An hour passed. We decided to check if the coast was clear in the corridor. There was a phone signal in the corridor, Amr went online and saw that more than 300 people had already been killed. It was about noon.

One of the protesters who was with us called a friend who was living in the block. We hurried upstairs to the flat. Someone opened the door and pressed his finger to his lips asking us to be quiet.

Inside, there were already more than 40 protesters hiding. It was eerily silent. The curtains were closed, there was no electricity, the only thing we could hear was the sound of the chaos outside. There were children, elderly people, young people. The man who opened the door confiscated our phones then motioned for us to move to the living room.

“How is it down there,” one of the protesters whispered as we found a place to sit on the floor. “Have they cleared the camp yet or are we holding them back?”

I didn’t have an answer, I stayed silent.

Some people on the floor had gunshot wounds, others were dealing with the side effects of tear gas. A doctor moved among the injured, treating them with the limited medical supplies he could find. Occasionally he would disappear into other rooms in the flat where there were more injured people.

We still didn’t know if Salim had made it out safely, or where he could be. We could hear the noise from the central stage of Rabaa; it meant that the security forces hadn’t cleared the sit-in yet and would still be looking for us.

At about 6pm, heavy explosions shook the building, the central stage went silent. We knew it was over. They had actually cleared the sit-in.

I drifted in and out of sleep, waking up to explosions throughout the evening. As the night wore on, gunshots slowed and the helicopter seemed to move farther away.

Puddles of blood, discarded shoes, bullet casings

At 5am the next morning, we were all awakened by one of the protesters who had left to find out what was happening.

He told us that they had completely wiped out the sit-in and that a curfew had been imposed, and that it would end at 7am. The presence of security forces was decreasing, he said, and soon it would be safe to leave.

He advised all of the protesters with beards to shave them off as he said the police in the area were targeting anyone who they suspected may have been involved in the sit-in.

As soon as I stepped outside the building, I smelled something burning. There were street cleaners sweeping, collecting rubbish and discarding broken tents.

An old woman standing next to the building looked at me. “Do you need anything?” she said.

I told her I had lost my shoes, she smiled and reached into a black bag she was carrying. She pulled out a pair of flip flops and gave them to me.

We headed back to where our tent once stood. There were puddles of blood on the floor. Discarded shoes, flip flops and clothing were strewn about in the street. There were bullet casings everywhere.

Cairo was back to normal, as if nothing had happened. People went to work as usual, the streets re-opened as if 1,000 people hadn’t just died there

We found the tent, crushed. People were carrying it away, our belongings were thrown on the floor. We found our clothes, I found my card for the London Underground, my university ID, my UK flat keys and I threw them into a ripped JD Sports bag I had been using to store my clothes.

We made our way out. We found a back route out of the square, aware that our blood-stained shirts and disheveled appearances could give us away as protesters.

We called Salim to check if he had made it out alive. He had survived and was waiting for us in the flat where we stayed in during our trip. It was at this point that we learned of the death of one of our friends, Ahmed Sonbol. He was a teaching assistant at the American University in Cairo, just 24 years of age, and had spent his time at the sit-in helping in the field hospital.

We hailed a cab and made our way to the flat. The reunion with Salim was bittersweet. In the space of 15 hours of broad daylight, we learned, hundreds of people had been killed.

There were so many funerals to attend that day, but we couldn’t bring ourselves to go. We spent the day mostly in silence, unable to comprehend what we had just witnessed, right in the middle of the city.

Cairo was back to normal, as if nothing had happened. People went to work as usual, the streets re-opened as if 1,000 people hadn’t just died there.

Rows upon rows of corpses in shrouds

In the evening we decided to visit a mosque that was being used as a make-shift morgue, after the mosque in Rabaa was burnt down by security forces during the dispersal.

The moment I stepped into El-Eman Mosque a strong smell hit the back of my throat, like a mixture of blood and sweat, a potent burning smell. It was a smell I could literally swallow.

On the floor, from the entrance all the way through to the back of the mosque, there were rows upon rows of corpses wrapped in shrouds.

Lists of names were put up near the entrance for families to find their loved ones. There were women sitting beside the lifeless bodies of their sons, husbands or fathers.

Men were breaking down as they found their loved ones wrapped in a shroud. There was an eerie silence, bar the occasional gasp of shock, or wail of a heartbroken person.

There was one section seizing the most attention, surrounded by photographers and journalists. As I got closer, the burning smell became more intense.

There were huge blocks of ice on top of the bodies.

One of the doctors pulled back the shroud from the head of one of the bodies - or what was left of it. The head was black, part of the skull was missing.

It took me a few moments to realise what he was showing me: these people had all been burnt to death.

To this day, not a single person has been held accountable for their actions in Rabaa. Indeed, the man who gave the order to clear the square, the army's then-commander in chief Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, has since gone on to become the president of Egypt.

We watched in awe as just two years later David Cameron rolled out the red carpet in London for Sisi, a man responsible for the death of our friends and thousands of others, including a British national, veteran Sky News cameraman Mick Deane.

One silver lining

As the dust settled over Rabaa, the huge divide in Egyptian society was far deeper than we ever could have imagined. We watched as friends and family, activists and those who called themselves supporters of human rights cheered on the massacre as if the blood of their fellow countrymen meant nothing.

To us, 14 August will forever serve as a reminder of the day I was given a second chance at life

It was a devastating realisation. They accused us of being members of the Muslim Brotherhood, failing to understand that people from all political persuasions had gathered in Rabaa to voice their stance against the coup.

Despite the ordeal that I went through, there was one silver lining: two days after the massacre, someone sent me a tweet of hope, and a year and a half later that person became my wife. To us, 14 August will forever serve as a reminder of the day I was given a second chance at life.

Mahmoud Bondok is the Head of Social Media for Middle East Eye and has a keen interest in digital media and technology

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: Protesters run from tear gas fired by Egyptian police as they try to disperse supporters of Egypt's ousted president Mohamed Morsi in a street leading to the Rabaa al-Adawiya protest camp in Cairo on August 14, 2013.

This article is available in French on the Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].