Disappearing the disappeared in Lebanon

On 30 August, the International Day of the Disappeared will once again be observed.

In Lebanon, where an estimated 17,000 persons are still missing on account of the “civil” war that ravaged the country - with plenty of outside help - from 1975 until 1990, it will mark yet another year of unanswered questions for family members of the victims.

Earlier this year, I spoke with one such family member: a silver-haired man named Abed, whose younger brother, Ahmad, joined the PLO in 1983 at the age of 17 and then promptly disappeared.

Over pineapple juice in the garden of his home in the tiny south Lebanese village of Maaroub, Abed recounted the decades of futile searches for Ahmad.

During one period, the family was strung along by an enterprising fellow involved in a missing persons scam industry; in exchange for several hefty payments, he produced what he claimed was an official paper from a prison in Aleppo, Syria, confirming that Ahmad was being held there.

An eventual visit to the jail by a Lebanese politician destroyed that myth. Reports that Ahmad had been spotted at Lebanon’s notorious Roumieh Prison also proved unfounded and the family continued to allow for the possibility that he had been delivered into the hands of either the Syrians or the Israelis by some sympathetic Lebanese formation.

The school day that never comes

Throughout Lebanon itself, mass graves from the civil war era have yet to be excavated - for various reasons. Most obviously, there is no mechanism in place to allow for their excavation, a willful oversight of sorts that illustrates the profound political-sectarian obstacles to coming to terms with recent Lebanese history.

Thanks in part to a post-civil war amnesty that essentially translated into an enthusiastic embrace of impunity, Lebanese civil warlords and militiamen were able to recycle themselves - with minimal difficulties - into the postwar political landscape. To this day, many of them continue to lord their powers over respective communities with divisive and fearmongering rhetoric.

But just how sustainable is a landscape forged atop unmarked mass graves and other superficially interred crimes?

In my recent travelogue on south Lebanon, Martyrs Never Die, I note that politicians with large quantities of blood on their hands aren’t in any hurry to go tracking down - or digging up - the disappeared. As part of the state’s refusal to engage in any sort of meaningful reckoning with the dark past, the civil war is not even taught in Lebanese schools.

But as many surviving relatives of civil war victims can attest, the past is the present. Forcibly denied information regarding their loved ones’ fates, family members are condemned to a sort of psychological limbo that often amounts to emotional torture.

Human beings are designed to grieve, when faced with personal tragedy, in order to process and eventually overcome the pain. In the case of disappearance, however, there is nothing concrete to process; it’s impossible to grieve the unknown.

The lack of closure can be linked to various manifestations of psychological and physical suffering and trauma. There are elderly Lebanese women who haven’t left the house in years, in heartbreaking anticipation of their missing sons showing up on the doorstep at any minute.

A 2013 report on Lebanon’s disappeared by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) quotes the brother of a missing person, who recalls their mother’s conduct following the disappearance: “I remember that whenever she cooked for us, we ate her tears with the food, because she never stopped crying.”

In another example of time coming to a torturous standstill, a Lebanese humanitarian worker in Beirut told me of a Palestinian mother he had interviewed whose four children had gone missing during the civil war in the refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila. The woman still kept her youngest son’s schoolbag in its spot behind the door in her house, in preparation for another school day that would never come.

Race against time

While time may continue to stand still for some, representatives of the ICRC in Lebanon are warning of a “race against time”: as aging relatives die, the likelihood of being able to one day identify exhumed remains is greatly jeopardised.

In July, I attended an ICRC press conference in Beirut where Fabrizio Carboni, head of the ICRC’s delegation in Lebanon, officially announced an initiative to collect Biological Reference Samples (i.e., saliva) from family members of the disappeared in order to assist in the future identification of any remains that are found.

Two samples will be collected from each person; one will be given to Lebanon’s Internal Security Forces and the other will be stored at ICRC headquarters in Switzerland.

At the press conference, while an older woman cried inconsolably in the front row, Carboni stressed that “answers” were still quite far off, and that - as much as the ICRC was doing to assist in the whole process - the organisation could not act as a substitute for the state.

An ICRC press release confirmed that “the samples will be used to extract DNA in order to identify human remains once a national mechanism is formed by the [Lebanese] government with the mandate to uncover the fate of the disappeared”.

Unfortunately, the “government” in question happens to consist of an illegitimate parliament that since May 2014 has not managed to elect a president, leaving the country without one. And while members of the contemporary Lebanese political class have not generally been known for any sort of commitment to the alleviation of popular suffering, the current government hold-up is a convenient excuse for inertia on the disappeared front, as well.

Compounding the inertia are claims that numerous people were disappeared from Lebanon to Syria - claims that now stand an ever-diminishing chance of being investigated given the ongoing brutal destruction of that country.

Meanwhile, regular attacks on Lebanon by the state of Israel and other murderous entities might perpetuate the narrative that the Lebanese don’t have time to deal with history.

But as Abed commented to me in his south Lebanese garden regarding the fate of his brother Ahmad and the other 17,000 disappeared: “We need closure.” The paramount need for a personal psychological ceasefire - the truth about what happened to Ahmad - hadn’t subsided even as Abed was forced over the years to endure Israeli bombardments and other shameless affronts to justice and human decency.

Another International Day of the Disappeared, another eternity of impunity. In Lebanon, the war is far from over.

- Belen Fernandez is the author of The Imperial Messenger: Thomas Friedman at Work, published by Verso. She is a contributing editor at Jacobin magazine.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

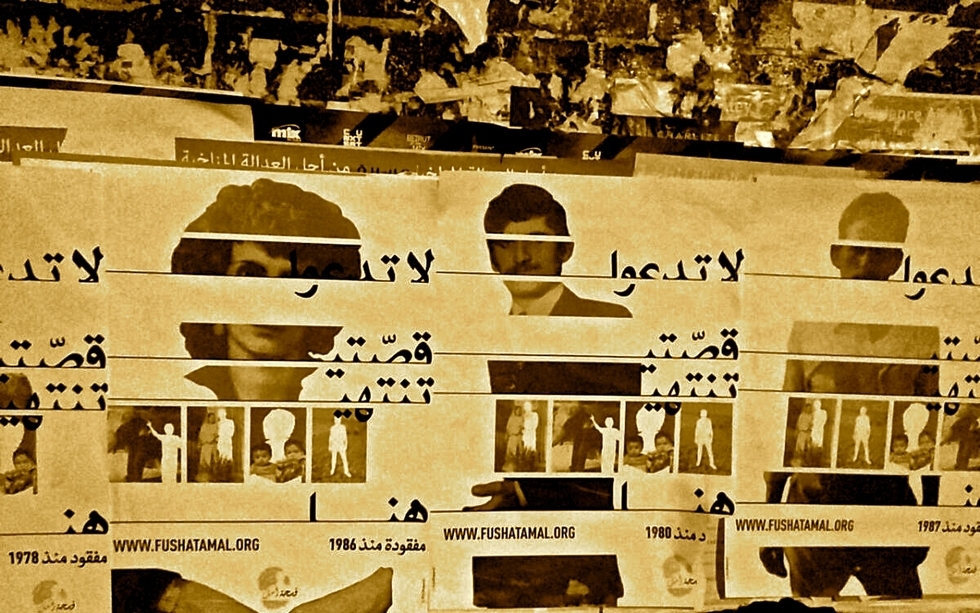

Photo: A photo of a poster from the Fushat Amal organisation on a wall in Beirut's Ashrafiyeh neighbourhood (MEE/Belen Fernandez)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].