Syria: War without end

Dozens of mediations and agreements, the latest between Russia and the US last week which has already fallen apart, have only made things worse in Syria.

At the end of August, the war took another complex, arguably more important, turn when Turkish troops crossed the border into the Syrian town of Jarabulus to support a new US-backed offensive against the Islamic State (IS) group.

The deployment of Turkish military alongside Syrian opposition factions will further fragment Syria and extend the duration of an already protracted conflict.

The occupation of Syrian territory by international players, diverging regional agendas and the multiplicity of local factions make a long-term solution appear elusive for the time being.

Occupied Syria

Turkey’s offensive into Syria was met with little resistance by IS. Cheered by Syrian rebels, the event is nonetheless a dangerous escalation in the conflict.

The operation, launched by the Turkish government under the Euphrates Shield banner, has allowed Ankara to capture some 850 square-kilometres of Syrian territory.

Occupation of Syrian territory has become commonplace in Syria since the onset of the 2011 revolution against President Bashar Assad. In 2015, a Hezbollah commander told this author on condition of anonymity that his movement had turned the Syrian town of Qusayr in western Syria into a strategic base and training camp.

Hezbollah also controls other Syrian border areas such as Qalamoun and has, according to media outlets, fortified bases in the mountains overlooking Zabadani.

Hezbollah’s sponsor Iran - whose security and intelligence services advise Assad - has de facto control of Damascus and has deployed high-ranking officers on battle fronts across the country. Iran has also provided the regime with expeditionary training, using Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) ground forces and intelligence services, and essential military supplies.

In turn, Iran’s ally in the war, Russia, has sent tanks, air-defence systems and more than 2,000 soldiers to its bases in Syria, specifically the Hmeimim Air Base near the city of Latakia, the naval facility in Tartus, and to a new base in Syrian desert city of Palmyra.

Foes of the Assad regime have also taken liberties in Syrian territory, with the US deploying over 300 military personnel in Kurdish areas in northern Syria. Last week US-led coalition forces bombed the Syrian army in Deir Ezzor, in what was called an accidental attack.

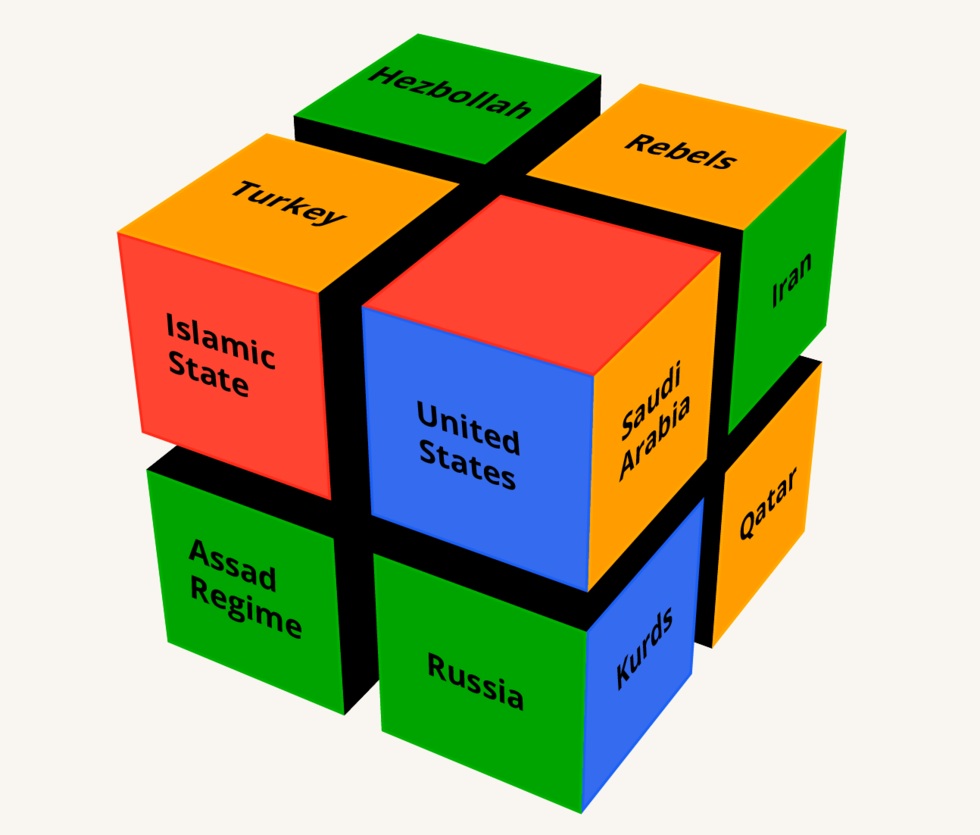

Rubik's cube of interests

Multiple regional players are each fighting their own war in Syria, which complicates any long-term solution.

While Turkey entered the Syrian conflict as part of the US-led coalition against IS, its priority is to put an end to the expansion of Kurdish forces in northern Syria which aim to connect different cantons from Hasakah to Afrin and form a contiguous Kurdish territory along the Turkish border.

Turkey’s ally in the war, the US pursues a crisis management policy in Syria primarily focused on the fight on IS, which by July had lost more than a quarter of its territory in Syria and Iraq.

Conversely, Russia’s goals in Syria are much better defined: Moscow is opposed to regime change that would set a dangerous precedent, and also fears the rise of militant Islamists and a possible contagion in its “near abroad”.

Russia’s partner in Syria, Iran, is defending more personal interests. The Assad regime is one of the main building blocks in the Moumanaa axis, an anti-western rejectionist alliance between Iran, Syria and Hezbollah that has allowed Iran to expand its area of influence from Tehran to Baghdad and Beirut.

The war in Syria has also largely served the interests of another of the Baathist countries’ neighbours: Israel. Ongoing fighting has depleted the Syrian army’s capabilities and is wearing down Hezbollah, Israel’s main adversary, which has lost hundreds of fighters in the conflict.

Israel has targeted Hezbollah, Iranian and Assad forces in Syria whenever they posed a threat as well as convoys of advanced weaponry to be transferred from Syria to Hezbollah in Lebanon.

Fragmented forces

Multiple and diverging interests are also replicated at the local level. There are currently hundreds of rebel factions in Syria, 30 of which boasting forces between 3,000 to 7,000 fighters, according to Syrian Sheikh Hassan Dgheim who follows military factions and spoke to Middle East Eye.

These groups include jihadists such as IS and Jabhat Fateh al-Sham, to Salafi Mujahid groups whose agendas are more localised and exclude global jihad, such as Jaish al-Islam and Ahrar al-Sham and other Islamic factions such as Ajnad Sham and the Free Syrian Army among many others.

On the other hand, the regime has been shored up by militias such as the National Defence Forces, the Syrian Nationalist Party (SSNP) brigades and private militias including Syrian Hezbollah, the Bustan association militias, the Desert Hawks and the Tiger forces.

These multiple undercurrents are symptomatic of the sad Syrian reality: because each side is backed by foreign powers, plentiful arms and supplies are sent to prevent the defeat of sponsored factions, further extending the war and aggravating the country’s fragmentation.

Multiple conflicting forces have become symptomatic of the Syrian conflict pathology. As a result, the regime may survive on paper while national institutions slowly erode, replaced by autonomous local entities.

The result? Most probably a de facto division of the country in different zones of influence, according to Marwan Muasher of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace who spoke to MEE. A worst-case scenario could see Syria unofficially dismembered in favour of nearby countries, a process that Turkey’s entry into Syria may foreshadow.

- Mona Alami is a researcher and journalist covering Levant politics. She is a non-resident-fellow at the Atlantic Council. Her primary focus is radical organisations. She holds a BA and an MBA in management.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Image by MEE Graphics

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].