Ramallah via Yarmouk and NYC: Young Palestinian artists vie for 'return' prize

RAMALLAH, Palestine - “I’m smiling while thinking of all the things I have yet to get done,” says Inas Halabi, a young Palestinian artist from Jerusalem. She is happy, and understandably so.

Around her are a group of artists under the age of 30, all of whom reflect the scattered lives of the Palestinian diaspora. There’s Aya Kirresh, also from Jerusalem, Ruba Salameh from Nazareth, Abdallah Awwad from Nablus, and Majd Masri and Asma Ghanem from Ramallah.

Others, however, are missing: Somar Sallam, a Palestinian refugee from Syria now living in Algeria, was unable to leave the country for fear of being barred from re-entry; and Majdal Nateel, best known for If I Wasn’t There, an installation of 400 paintings depicting the silenced dreams of children killed in 2014's attacks on Gaza, was unable to obtain a travel permit out of Gaza.

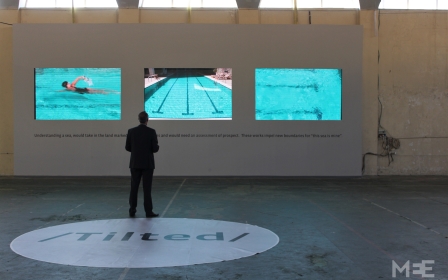

Yet the work of all nine, including the Beirut-based Noor Abed, is currently being exhibited at Dar Sa’a, a traditional Palestinian house in the centre of Ramallah, as part of Pattern Recognition.

All were participants in this year’s Young Artist of the Year award organised by the AM Qattan Foundation, with Halabi named the overall winner.

“I’m interested in the unreliability of facts and the impossibility of accessing a complete narrative,” says Halabi, not long after the winning of her award. “As such, I find myself constantly experimenting with non-linear structures. [In other words] I try to create a platform from which questions regarding the construction of history, memory and national identity can be examined and explored. There are many similarities in what the role of an artist and the role of a historian is, and the overlap between these fields interests me.”

Family history as art

Working predominantly with video, original images, sculpture and text, Halabi’s work explores various historical and political narratives related to collective memory, national identity and forgotten histories, and it is her video installation Mnemosyne that awaits visitors to Dar Sa’a.

The title of the project is borrowed from the Titan goddess of memory, while the starting point of the work is a scar on the forehead of her grandfather – the result of an Israeli bullet in the late 1940s. For Mnemosyne, members of her family were filmed individually as they narrate their version of the same event, with Halabi focusing on the sagas of myth and the construction of memory.

“By scratching the surface of family history, the project explores the scar as a foundational hinge that arranges reality,” explains Halabi. “The project also considers how one can play the role of a historian when the primary source is no longer there. ‘We do not remember. We rewrite memory much as history is rewritten.’ As such, recollection becomes an act of transformation rather than reproduction."

“Mnemosyne was filmed in the north of Palestine, next to the village of I’billin (my mother’s village) where my grandfather’s barracks were located. The final piece included the stories of eight maternal aunts and uncles, my mother and my grandmother. One of the most challenging and important parts of completing this work was bringing the brown couch seen in the video to Dar Sa’a. It was originally located in 1948 Palestine.”

The runners up

Dar Sa’a was renovated a few years ago by Riwaq, an organisation specialising in the preservation of Palestinian architectural heritage. It is now filled with elegant Ottoman wall cabinets, many of which exhibit the work of the young artists. Included among the works inside is Masri’s exploration of the iconic image of a Palestinian fedayee fighter as it travels in different guises through Palestinian art history, and Awwad’s confusing sculptures – it is unclear whether they are in a state of construction or demise.

It is the immediacy of Sallam’s video work highlighting the human tragedy of modern displacement, however, that is arguably the most impactful.

“I have been with my family in Algeria for four years,” says Sallam, who was born in Damascus and grew up in the Yarmouk refugee camp. “Algeria is a beautiful country and the culture of the community is not much different from the environment from which we come. But this transition has not been easy for us.”

Like thousands of Palestinians from Syria, Sallam and her family are refugees for the second time. Born into a family of artists – her father Zaki Sallam is a well-known Palestinian sculptor – and a graduate of the faculty of fine arts at Damascus University, she took second place in this year’s competition behind Halabi.

“Art is a way of life,” she tells me. “Through it life is easier to confront and my video work highlights the experience of thousands of Palestinian-Syrian refugees – displaced for the second time from their place of first asylum in Syria, where they built their lives and brought up their children, only for all to be lost again after all that was built because of the latest forced exile. Every one of them has had to start their life again from scratch – to raise and build and survive.

“I have tried to embody the process of building through the weaving of crochet, because it is a process that is slow. The effort that it requires is apparent in every woven stitch. A large piece comprised of multiple parts that are not perfect takes a long time to create, only for what has been built or woven to be destroyed again.

“Most of what this work wants to highlight is the human tragedy caused by displacement."

“Most of what this work wants to highlight is the human tragedy caused by displacement. Our days are not like the average day of ordinary people around the world. Our days are heavy and slow. We try throughout the hours to be productive, to work and to build our lives, but our lives will never be perfect as long as the threats to continue exiling us remain; as long as displacement keeps renewing itself because of the distinct lack of a solution to our core problem, which is our need to return to our native villages and cities.”

'One cannot do architecture without art'

"It is the second time that the Young Artist of the Year award has been held within the context of Qalandiya International, a joint contemporary art event that takes place every two years – this year crossing the borders of Palestine to Amman, Beirut and London.

It is within the framework of Qalandiya International’s theme of re-imagining the artistic conceptualisation of "return" – called This Sea is Mine – that Nat Muller, curator of the competition, formulated a curatorial framework in which "return" is viewed from a perspective of repetition, pattern and rhythm.

“The works in the show look at how ‘repetition’ can be used as a critical strategy to explore the grey zones between, for example, fact and fiction, original and copy, ruin and repair,” says Muller. “These are pressures that, in some form or other, Palestinians deal with on a daily basis, from ‘facts on the ground,’ to the viability of a Palestinian state, to the cycle of violence and reconstruction. But how to capture these sensibilities in a more focused way and artistically? This is in essence what the artists are doing in their projects.”

Amongst them is Aya Kirresh, an architectural engineer by both education and profession who describes herself as an "ArchiArtist". Her work for the exhibition is an investigation into the history of cement in the Palestinian construction industry through a series of repetitive sculptural experiments.

“One cannot do architecture without art,” she says with the hint of a smile. “There is a chemistry between the two fields and I always find common ground between the two disciplines, although it sometimes seems strange to my clients when I try to explain connections, especially in the non-artistic community. But they feel a harmonious vibe that sort of marks my work.

“Every building has a certain rhythm within the urban fabric and the materials used to build it set its form. Working on site designing and supervising residential buildings in Jerusalem and being surrounded by all the concrete and the building materials, I wanted to experiment with those materials with my own hands.

“Of course the social, cultural and political aspects of Palestine are not normal, which is enough to inspire an artist,” she adds. “But what makes it more inspiring is connecting it with the world and expressing it with non-conventional media. Like connecting indigenous media with modern media. It’s wonderful when one is inspired by a desire to explore possibilities.”

All of the featured artists are inspirational in their own way. Abed, for example, is interested in creating “situations that highlight the repetitive absurdity of the everyday,” while Ghanem (placed third) ploughs a sometimes lonely field in the world of sound art and experimental music.

“I am always hugely impressed with the resilience I find in places like Palestine and the insistence to produce art, often against the odds,” says Muller. “That is, in and of itself, a political act. I think what [young] Palestinian artists often have to deal with is pressures and expectations from the inside (their own society) and from the outside (Western institutions) on what their art should be about (identity, homeland, the Palestinian plight, the Israeli occupation) or look like (iconography like keys, oranges, olive groves).

“I am always hugely impressed with the resilience I find in places like Palestine and the insistence to produce art, often against the odds”

“Increasingly in Palestine, there are also market forces to reckon with, which privilege some mediums (painting) as more commercially viable than others (video, live art, installation etc). It is very important that artists do not end up reproducing a certain visual vocabulary or theme only because they think this is expected from them as Palestinian artists. Young artists need time to develop their own visual and conceptual language as free as possible from the aforementioned pressures.”

Pattern Recognition runs until 31 October

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].