Yet another Palestinian family fragmented by the Israeli occupation

Occupied East Jerusalem - “Even though I had eight children, I have never truly experienced being a mother,” Layla Issawi, 70, said after slowly propping herself up from afternoon prayers in her quiet home tucked away in the neighbourhood of Issawiya. “Each time my children came back to me, Israel would just come and take them away again.”

The revolving door of Israeli prison is a routine Layla has come to know well.

Framed photographs of her children, all of whom are now between the ages of 30 and 45, decorate the shelves and walls of the Issawi family home. Most of them are pictured separately. There was only a two-month period in 2014 when Layla was able to see all of her family together.

Today three of her children, Samer, Shireen and Medhat, are imprisoned in Israel after being detained again in 2014. Layla’s husband Tareq, 72, tells MEE that his children have been targeted for their political activities in the community.

The ageing couple organise their days around visits to see their imprisoned children in Israel, who they are permitted to see once every 15 days for 45-minute sessions.

Tears of loss

Tareq told MEE that the first to be taken were Medhat and Rafat, during the first Palestinian Intifada, which erupted in 1987, when they were between the ages of 13 and 15-years-old. Israeli soldiers detained the two from their home during the early morning hours on the day they were scheduled to have an exam at school.

When the soldiers first detained their sons, they assured Layla and Tareq they would only take them for an hour or two. “But it took them a year to finally bring our children back to us,” Tareq said, slowly shaking his head as he reminisced on what was the start of a long relationship with the Israeli prison system.

Medhat has been detained a total of seven times by Israeli authorities. He had already spent half of his life, at least 22 years, inside Israeli prisons before his most recent detention in 2014. Rafat spent six years in total in Israeli prison during three separate sentences.

Layla’s other sons Firas and Shadi have also spent four and 12 years in Israeli prison respectively. Firas was 18 when he was first taken by Israeli soldiers, while Shadi was just 16.

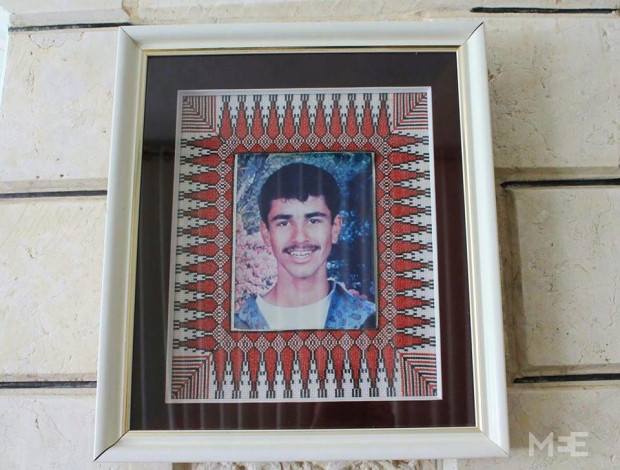

In 1994, Layla’s son Fadi experienced the deadly side of Israeli occupation: he was shot to death by Israeli forces during protests in Issawiya when he was 17-years-old.

Layla’s eyes quickly become blurred with tears as she speaks about Fadi, as her drooping eyes wander to an old photo of the slain teenager hanging on the wall. The 17-year-old was protesting the massacre of 29 Palestinians at the Ibrahimi Mosque in Hebron by an Israeli settler.

When the Second Palestinian Intifada broke out across the occupied Palestinian territories in 2000, Layla’s son Samer was the next to be targeted by Israeli forces.

In 2002, Samer was sentenced to 30 years in Israeli prison for political activities during the Palestinian uprising. He had previously spent a year and a half in prison. He spent 10 years behind bars before being released in 2011 as part of the Gilad Shalit prisoners exchange.

However, Tareq and Layla’s much-awaited reprieve was short-lived. Samer was detained again several months later. This time around he rose to national prominence after going on a 266-day hunger strike, one of the longest in history, before finally being released at the end of 2013 after serving more than 17 months.

Altogether only once

Slowly approaching one of the shelves lined with several portraits of her children, Layla excitedly takes one from the set showing Tareq and Layla posing beside three of their sons. The photograph was taken when Samer, Medhat and Rafat were all held in Israel’s Beersheba prison in the 1990s.

“It was a happy time when Samer was released,” Tareq told MEE. “It was the first time in decades that the Issawi family were all together.”

“We had one huge feast during those weeks,” Tareq added, as a slight grin deepened the wrinkles on his face. “We had one big feast during this whole lifetime together.”

But in March 2014, Israeli forces detained Medhat and his sister Shireen, a prominent Palestinian lawyer working on rights of Palestinian prisoners who had also previously spent time in Israeli prisons. Medhat managed the Al-Quds Office for Legal and Commercial Affairs where Shireen worked to provide assistance to Palestinian prisoners who faced difficulties seeing their families.

An Israeli court sentenced Shireen and Medhat to four and eight years in prison respectively in March this year for providing funds to Palestinian prisoners and communicating with illegal organisations, which encompasses the majority of Palestinian political parties.

Just three months after the detention of Shireen and Medhat, Samer was once again detained during a widespread detention campaign called “Operation Brother’s Keeper” when three Israeli teenagers were kidnapped in the West Bank. Israeli authorities reinstated his full sentence from his detention in 2002, forcing him to serve the next 20 years in Israeli prison.

Their daughter Rasha, the youngest of the eight, is the only one of their children who has not been imprisoned by Israeli forces.

Gruelling visits

Tareq and Layla, now at retirement age, told MEE the trips to the prisons to see their children have taken a toll on the aging couple’s health. Each of the children are locked inside different prisons across Israel, making visits time-consuming and exhausting.

Layla has suffered from complications with her blood sugar and even walking up and down stairs has become a difficult task. Yet Tareq says a typical visit to see Samer in Israel’s Nafha prison starts at 4am, and the couple does not arrive back home until seven in the evening.

Meanwhile, Medhat and Shireen’s visitation times are scheduled at the same time on Monday every 15 days, forcing the elderly couple to split up between two Israeli prisons in order to visit them both.

40 percent of the male Palestinian population has been detained at some point in their lives

“I just want to be able to see my children six times a month without having to choose between them,” Layla said. “But Israel doesn’t care about Palestinian lives. They will not help us or make our lives easier.”

Layla said she was unsure of how much longer she could continue making the gruelling trips to see her children. “I am getting too old and it has become too difficult. Even the waiting time to enter the prison can last up to three or four hours.”

But Tareq and Layla were quick to point out that their story was not unique in the Palestinian community. “Our story is the story of all Palestinian families,” Layla emphasised, naming a long list of fellow Palestinians who have lost children to Israeli prisons and bullets.

According to the prisoners’ rights group Addameer, 40 percent of the male Palestinian population has been detained at some point in their lives, with 20 percent of the total population spending at least one stay in Israeli prison.

Home demolition orders

The order came in May, two months after Shireen and Medhat were sentenced. Israeli authorities are now ordering Layla and Tareq to demolish their home which they have lived in for more than three decades.

Tareq says the house was built without Israeli-issued building permits, much like the majority of Palestinian homes in East Jerusalem, as the permits can cost up to $75,000, while only 11 percent of land in East Jerusalem is zoned for Palestinian residential construction.

But the Issawi family is no stranger to Israeli demolitions. During Samer’s nine-month-long hunger strike, Israeli forces demolished his brother Rafat’s home, and also detained his other brother Shadi at the time, in what the family says was an attempt to pressure Samer to end his strike.

According to Tareq, Rafat still owes a million and a half shekels ($393,691) to Israeli authorities for fees, with the interest still accumulating, that Palestinians must pay Israel following home demolitions. Rafat now rarely ventures out of Issawiya, in fear of running into Israeli military checkpoints that are routinely set up between Palestinian communities in the occupied territories.

“Everything the Israelis do to us is connected to our children,” Tareq says. “For us [Palestinians] every part of our lives are controlled by the Israelis.”

Targeted punishment

Daniel Seidemann, a lawyer from the Israeli nonprofit Jerusalem Terrestrial, told MEE that he “would not rule out the possibility by any means” that the Issawi family were being targeted with a demolition order for the political activities of their children.

“There are thousands of outstanding demolition orders on Palestinian homes in East Jerusalem,” Seidemann said, adding that until recently Israeli authorities carried out the demolitions randomly, without any clear system. “It was the equivalent of being hit by lightning.”

But recently Seidemann has seen a pattern in the home demolitions. “What we are now witnessing is a general and targeted collective punishment of Palestinian communities.”

'What we are now witnessing is a general and targeted collective punishment of Palestinian communities.'

Seidemann says the home demolitions are carried out more frequently in Palestinian neighbourhoods where political activism remains strong in order for Israeli authorities to “settle the score,” while targeting Palestinian individuals and families.

“But this is our life,” Layla quietly muttered as she leaned back on her chair. “It is now just Tareq and I, and our son Shadi in the house.” Layla says that Shadi, 32, refuses to get married until Samer is released from prison and they can hold the ceremonies together.

“All Palestinians know this is happening to us because our children fight for justice and freedom,” she said. “But I still pray everyday that in our lifetime we will once again see all of them free.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].