The Druze of Golan: Caught between a rock and a burned place

GOLAN HEIGHTS - A sofa teeters on a mound of earth overlooking rebel-held Syria, incongruous in the twilight. Abruptly and silently, dust billows from the foothills of Mount Hermon. The roar of a missile impact follows several seconds later.

Abandoned beside the settee is an Israeli tank, left to rust with its muzzle gaping towards Syria. It commemorates a previous war, in 1973, when a coalition of Arab nations unsuccessfully attempted to seize back land previously lost to the Israelis.

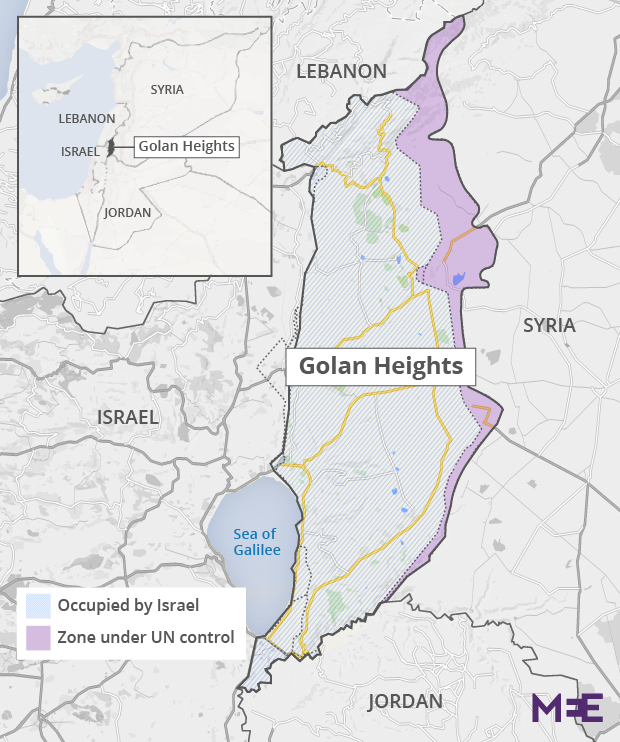

To the 20,000 members of the embattled Druze minority still living in the annexed Golan Heights, the tank is also a reminder of a half-century spent under Israeli occupation. From this vantage-point, they can watch munitions rain on their relatives’ land across the Demilitarised Zone (DMZ), and ponder the twist of fate which means their occupier is also their sole protector from the horrors of the Syrian War.

Windfall from Damascus

Toiling among his sedate orchards, moustachioed Nasm Khattar is a picture-book Druze apple farmer. The former teacher lost his job in the 1970s after being arrested for unspecified “political reasons” around resisting the occupation.

His ties to his motherland are both ideological, “the land is Syrian, the product is Syrian, the people are Syrian,” and practical. With the Israeli government underwriting its settlers at the expense of the indigenous Druze, Khattar could only make a living through subsidised sales to Damascus. Of course, this is now impossible.

Though common, Druze support for Assad is by no means universal. “Syria is not a republic, it’s a farm,” Druze activist Salman* says. He describes the autocrat as a farmer, feeding his people like livestock even as he extracts the wealth from their land: “and, like a farmer, now he is harvesting them”.

Where it does exist, Druze fealty to the reaper of Damascus is essentially pragmatic, borne out of generational fear. Jabhat Fateh al-Sham, the renamed al-Qaeda affiliate al-Nusra Front, surrounds Druze villages along the Syrian border, and are just the latest militant group to view the long-persecuted religious minority as heretics.

Though the al-Qaeda splinter group markets itself as the smiling face of the moderate opposition, in June 2015 its fighters massacred 20 Druze civilians. To avoid further slaughter, Syrian Druze are dependent on their own ad-hoc militias, the marketing nous of al-Sham’s leadership, and the shaky support of the Assad government.

Khattar says he does not blame the rebels themselves. Rather, he sees the revolution as orchestrated by foreign actors, to the detriment of Druze, Sunnis, and virtually everyone else. “We’re losing money, but people are losing their lives,” he says ruefully, tossing a bruised apple from a gleaming mound of windfall.

Hippy settlers

Twenty thousand Israeli settlers live on Druze land in the Golan. They do not often share the zealotry of their West Bank counterparts – to most, the Golan is simply an attractive place to live – but their homes are no less illegal under international law.

Indeed, the vaguely hippy vibe in the region’s kibbutzim is arguably more pernicious, masking an aggressive drive by the Israeli government to secure its hold on the Golan. Hard-right Education Minister Naftali Bennett recently announced plans to quintuple the number of Israeli occupiers, and construction is underway behind every stand of pines.

“I had a Druze taxi driver yesterday,” a recently returned Israeli backpacker blithely says, “and he was really friendly. We talked about the war, and I said, ‘I bet you’re glad we took over the Golan now, aren’t you?’” And how did the taxi driver respond? “Oh, he said nothing really. He laughed.” (The same backpacker will later explain that there are two things to avoid when hitchhiking – “old men and Arab accents”).

Harvesting in the minefields

To Druze farmer Faisal, unconstrained by the mandatory politeness of the tourist industry, the takeover is no joke. “The border is not the problem,” he emphasises. “Israel is not a big country. Everybody lives near a border.”

Though his vineyard abuts the mine-strewn DMZ, he is less concerned by his Salafist neighbours than he is by the steadily encroaching occupation. Thanks to discriminatory Israeli rationing, he has water for only five months a year. And while settlers string fairy lights through their gardens, he says, his entire farmhouse is cut off from the power grid.

'He has water for only five months a year. And while settlers string fairy-lights through their gardens, he says, his entire farmhouse is cut off from the power grid'

Hallaby is responsible for meting out scarce water reserves to struggling farmers like Faisal. He points out an old irrigation system, destroyed in 2014 when a buried Israeli ordinance was discovered and the land mine had to be blown up.

Even in the absence of explosions, his job is near-impossible. “The settlers get five times as much water as we do, though we pay nearly twice as much,” he says.

Ninety-four percent of land in the Golan is now given over to Israeli use, the settlers sucking up so much water they have come close to draining the shimmering Lake Ram. And with $108m recently earmarked by the Israelis to establish 750 new farming estates in the Golan, life on the scraps of land remaining to the Druze is only going to get harder. “If the settlers worked this way, they would starve,” says Faisal.

Fearing recriminations, Hallaby only smiles bashfully when asked why this discrimination occurs - but Faisal is forthright. “The state is here to protect Jews, not Arabs.” Israel’s recent overtures to the Golan Druze, by turns aggressive and seductive, are understood as mere political machination. “Many Arabs serve in Israel’s army, yet we’re not allowed to build on our own land. I won’t be fooled by this country,” adds Faisal.

In neighbouring Majdal Shams, children’s plastic push bikes and pick-up trucks are scattered in the shadow of a hulking Israeli army base. Druze activist Salman says the town’s 11,000 Druze residents are being used as a “human shields”. He points out hazards from the balcony of the anti-occupation organisation al-Marsad. “You see that park? It’s not a park. It’s full of mines.”

Druze activist Salman says the town’s 11,000 residents are being used as a 'human shields'

Israeli expansion is burgeoning here, too. In September, a home demolition of the kind so bitterly resented in the West Bank was carried out in the Golan for the first time.

The government’s recent seizure of 82 square km of land around the village to build a nature reserve might not be overtly linked to the war, but with Naftali Bennett describing the Syrian crisis as a “rare opportunity” to make the “big mountain of the Golan… Israeli,” the connections are not hard to draw.

In a region where the tourist shekel is so vital, the view itself is a natural resource. And with the DMZ to the east and over-developed farmland to the south, the Hermon National Park will also choke off the remaining space for expansion in the over-crowded town.

“I remember when it was all gardens,” says Salman, his finger falling from the mine-seeded hilltop to the jostling roofs below. “Now, it’s a mass of cement.”

The chameleon people

“Are you enjoying Israel?” Druze in Majdal Shams will politely ask. It is a question you would never hear from a Palestinian in East Jerusalem. To Salman, this is evidence “the occupation has got into their heads,” but some locals embrace their normalisation into Israeli society.

As Majdal Shams businessman Majd Abu Saleh relaxes on his balcony with a cup of tea, a chocolate yoghurt and a roll-up cigarette, artillery cracks and roars in the distance.

Abu Saleh says he has spent too many nights watching red tracer fire arc over Mount Hermon to think wistfully of his motherland. “It would be stupid to say I’m Syrian, when Israel gives us social security. If I lived over there,” – he gestures towards the border and blows his cheeks out in dismay – “what would happen to me?”

To visit Majdal Shams is to experience a surreal layering of hipsterism and human rights abuses. In a brazier-lit venue beside Lake Ram, the sound of war is temporarily drowned out, as dreadlocked Druze saxophonists jam with bongo players from Haifa. Tapping his foot to his girlfriend’s drumming, 23-year-old Amin says he is no fan of the occupation. “The Israelis say they’re here to protect us? Yeah, right. They’re here to protect themselves,” says Amin.

To visit Majdal Shams is to experience a surreal layering of hipsterism and human rights abuses

Nonetheless, his life philosophy is emphatically secular. “I have a lot of good friends who are Israeli,” he stresses. “It’s your choices that make you who you are.” His feel-good liberalism is a mirror image of the Syrian Druze’s pragmatic alignment with the Assad government.

“You know the chameleon?” Abu Saleh asks. “If the wind blows left he moves left, if the wind blows right he moves right. The Druze have to be smart, politically.” Taqiyya – the Islamic custom of concealing one’s cultural or religious identity to avoid persecution – has been a tenet of Druze theology for a millennium.

As al-Sham fighters and Assad forces pound one another with rockets, the piercing song of a muezzin breaks out in rebel-held territory, cutting through the still air of the demilitarised zone.

Hader, a Druze village just across the border from Majdal Shams, is silent. The lights of Majdal’s bars and restaurants gleam in the gathering night, but the streets of Hader are dark, its residents fled or cowering in their homes.

Caught between a rock and a burned place, the Druze of the Golan Heights seek shelter where they can.

Some names have been changed at interviewees’ request.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].