Ethiopia’s mega dam: Why, in Egypt, the sons of the Nile are worried

Qena, EGYPT - Egyptians have revered the Nile, the source of their civilisation, since they first set foot in its valley thousands of years ago.

Herodotus, writing around 450 BC, said that “the Egypt to which the Greeks go in their ships is an acquired country, the gift of the Nile," a reference by the ancient Greek historian to how the river’s waters replenished the soil, and made farming possible.

The people worshipped the river as the god “Habi,” chanting and praying: “You are unique. You created yourself from within. Nobody knows your essence.”

'Agriculture is the lifeblood of the village'

- Mohammed, farmer

For good reason: today the 6,800 mile-long river is a vital source of the country’s well-being and growth across agriculture, livestock, transport, tourism, drinking water and power generation.

Millions of Egyptians have continued their ancestral traditions and live within a few kilometres of its banks. They are inseparable from the Nile, for it is the godfather of the Egyptian peasant, with who it has a close, tangled relationship. “Agriculture is the lifeblood of the village,” Mohammed, a farmer, told MEE.

But the construction of a new dam is casting a shadow over the Nile, leaving Egyptians – and farmers in particular – worried for the future.

That dam, however, is being built not on Egyptian soil but far beyond its borders.

Why Egypt is worried

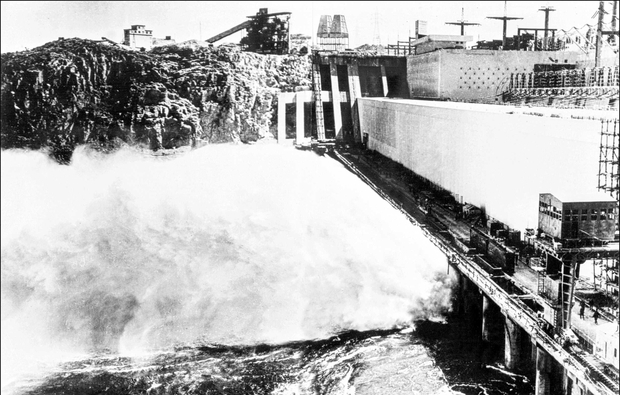

Ethiopia began building the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam - known in Egypt as the El Nahda Dam - in April 2011, at a then-cost of $4.7bn. The structure – which is 1,800 km long and will have a volume of 10 million m³ - is expected to be completed in July next year. It is regarded as central to the country’s ambitions to become an economic powerhouse in Africa.

The government in Addis Ababa has said that the project will not harm the interests of other nations, including Egypt.

Attempts were made to build the dam during the era of former Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak, who asserted that Egyptian access to its annual quota of the Nile’s waters is a matter of life or death. But Mubarak was overthrown in January 2011: construction work on the dam began six months later.

The current Egyptian government has said that while Ethiopia has a right to plan for its future, it will not forfeit Egypt’s historical rights to access the waters of the Nile, rights which were ingrained in international conventions signed during the period of European colonial occupation.

The dam is intended to be 175 metres high. Many Egyptians – and indeed Sudanese, who will also be affected – fear that their towns and villages will be swept away should it ever collapse.

'Most dams in Sudan and Egypt would collapse under the pressure of the flood waters'

- Hisham, commerce graduate and farmer

Hisham, 30, a business graduate who also works as a farmer, said: "Ethiopia intends to build a disastrous dam in terms of height and slope. This causes us Egyptians chronic concern about the dam’s collapse. Most dams in Sudan and Egypt would collapse under the pressure of the flood waters."

Egypt is also worried that the new dam will harm its ability to generate hydro-electric power. Much of Egypt's electricity comes from the Aswan High Dam, whose waters may be affected by its new upstream rival. As a result the government in Cairo is looking to diversify where it gets its power from, such as the nuclear plant project in the El Dabaa area.

“There’s an awful lot of politics… the Egyptian government is playing down the issue, because it realises that Ethiopia is a growing power in the region and it wants Ethiopia on its side,” says Kieran Cooke, an environmental writer focusing on the Middle East. He says that it is too early to know what the impact of the dam will be on Egypt: “It’s very difficult to judge until the dam is up and operational. I think at the moment there’s an awful lot of emotions going around and I don’t think anyone is particularly well informed – either the Egyptian government itself, or the farmers or these politicians who are perhaps using the whole issue to undermine the Sisi government.”

Farming means survival

But it is farmers who are likely to be most affected by the new dam. Mohammed, 50, is a government teacher who followed his ancestors and works as a farmer in the governorate of Qena, about 600 km south of Cairo. Like others interviewed by MEE, he preferred not to give his full name. He said that, like many others, he was supplementing his government income with farming, something he attributed to Egypt’s dire economy and rising cost of living.

He explained: “Agriculture guarantees me a dignified life. I inherited it from my father and grandfather, although I am a government employee.”

Now he is teaching his sons how to be farmers, including lessons about sowing seasons and irrigation.

The Nile is the only source of irrigation in the village due to its proximity and low cost. Before the Aswan Dam, the river flooded the land, which could then only be farmed once every year. Recent decades have brought more control over the waters of the Nile, allowing farmers successive opportunities to cultivate - but that freedom is, many Egyptians say, threatened by the project in Ethiopia.

“The reasons behind Ethiopia building the dam are investment and politics," Mohammed said.

The dam’s sources of funding include Saudi Arabia, the UAE and several European countries. Israel, which is keen to become more involved in Africa, is also supporting the dam. Ethiopia has a large Jewish population, some of whom travel to work in Israel.

Many blame Ethiopia

The dam may be a source of pride in Ethiopia - but many Egyptians look down on their neighbour as a poverty-stricken country. Sometimes that tips over into nationalism among those who will be most affected.

Mostafa, 49, told MEE that Egyptians are willing to sacrifice their lives if they had to to defend their right to access water, even if it results in military intervention. But he added: “The issue can only be settled politically."

'There was a golden opportunity before the dam to preserve the rights of Egypt. It is too late now.'

- Hisham, commerce graduate and farmer

Hisham said: “There was a golden opportunity before the dam to preserve the rights of Egypt. It is too late now.”

He pointed out that the Ethiopian government had taken advantage of Egypt’s political vacuum and overthrow of governments in 2011 and 2013.

“It is Ethiopia’s right to build investment and water projects that guarantee its people a decent living, just as is the case with Egypt,” he said. “However, this shouldn’t prejudice Egypt’s right to its water quota.”

Hisham said that there were other projects in and around Ethiopia which could make better use of water, particularly after the El Nino weather phenomena that sparked famines in the region in 1997 and 2006.

He concluded that Ethiopia has failed to comply with international conventions. Instead, he said, it had initiated the Entebbe Agreement with Nile Basin nations upstream and downstream of the project such as Kenya, Rwanda and Uganda. Egypt and Sudan have yet to sign.

Farmers: We have no voice

The general consensus among the farmers who spoke to MEE is that the dam will definitely affect them, if not in the immediate future.

Instead they fear for future generations, who will, they say, bear the consequences of the mistakes committed in the present. With time, they argue, the production of water-intensive crops such as grains, rice, bananas and sugar cane will wither away, forcing many farmers off the land and impacting Egypt’s agricultural exports.

They are also worried that their voices are not being heard by the government, which discusses the crisis behind closed doors; or the media, which explores the issue through interviews with economists, politicians and other experts – but never farmers.

Even a relatively minor change to water levels on the Nile caused by the dam would have a huge effect on farmers, says Cook. “ If you look at population patterns and the demographics of Egypt… so much of the population is of course based along the Nile. If there was an impact, and it only needs to be a slight drop in water levels, it would be critical for Egyptian society.”

The time has come to provide a space for farmers to express their opinions, hopes and solutions, in the hope that officials will listen.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].