How Putin and Erdogan divided up Syria

This coming week, it will be exactly 13 months since Russia moved militarily into Syria.

At the time, Russia’s brilliant, if ruthless, move on the strategic chessboard infuriated Turkey. It seemed to block the way for the military incursion campaign which Ankara still dreamt of to dislodge President Bashar al-Assad and replace him with a Sunni-led united Syria. Russia too seems to have believed at the start of this year that it would face the united opposition of Turkey and Saudi Arabia in Syria.

But as things have turned out, Russia’s entry into Syria eventually unblocked the three-year stalemate for Turkey - after it had done a volte-face of its own and President Erdogan reached an understanding with President Vladimir Putin in June.

That deal was probably inspired by a Turkish need to restore normal economic relations with Russia, but it swiftly turned out to be a winning compromise for it in Syria as well.

Striking the Kurds

At the present, though Russia is securely entrenched in the western areas of the country ruled by Assad and unlikely ever to be dislodged, Turkey, with Putin’s approval, now has tanks and soldiers in the north of the country. The long-frustrated Turkish dream of a "safe zone" for refugees running 55 miles westwards from Jarabulus now seems to be realisable.

More importantly, Turkey is also able to simultaneously tackle the two threats it sees on its southern borders: the autonomous Syrian Kurdish enclaves and the Islamic State (IS) militant group.

Borrowing the tactics of the US-led coalition against IS, its planes bomb the Syrian Kurds while its local allies in the Free Syrian Army fight them on the ground, pressing on Tel Rifaat and Marea, and the outlying Kurdish enclave of Afrin, and also Manbij, the town recently captured from IS by the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces.

With the Kurds excluded, Ankara hopes to work inside the US-led coalition in a coming assault on the IS capital of Raqqa, an outcome which accords well with Russia’s strategic goals in Syria.

Each major move by Turkey seems to be preceded by a direct telephone conversation between the two presidents, indicating that, though each has probably told the other the general outlines of the new order which they intend to create in Syria, they still need to be sure of the other’s specific acquiescence.

Strategic breakthrough

A year ago, Putin probably would not have relished the idea of a Turkish-backed Sunni zone in much of Syria and his ally Bashar al-Assad must detest it.

But, if IS’s hold on northeastern Syria does crumble under the Turkey-backed onslaught on it, some sort of stable authority is likely to emerge in place of the present fragmentation as Turkey and its allies consolidate their hold in the north and Turkey acts as its guarantor.

More importantly, Putin knows that cooperation with Turkey is beginning to glue it into a long-term partnership with Russian interests. It is not simply that Turkey’s relations with the US and NATO are tense and mutually suspicious, and steadily deteriorating.

The arrival of Russia in Syria could be its biggest strategic breakthrough since the distant times when it arrived on the Black Sea in 1774. It transforms the strategic balance in the Eastern Mediterranean region, effectively encircling Turkey and pruning its strategic importance to its Western allies.

This might have started alarm bells ringing in Ankara under many earlier governments but today, the eyes of government strategists and commentators in the Turkish capital are almost exclusively focused on eliminating opponents of its Sunni allies in both Syria and Iraq and then building those groups up in the medium term into stable frontline political entities working closely with Turkey.

Having been frustrated from gaining this prize for so long and paid such a huge cost, it is understandable that Ankara is determined not to miss it now.

Two Syrias

So what we are seeing in Syria seems like a drift towards the emergence of two zones of influence: a Russian-backed littoral state under Assad, claiming to be the sole government of the country, and a "Free Syria" backed by Turkey.

This might sound a bit like Cold War Germany, but perhaps a better parallel, and a more Middle Eastern one, is the division of Iran into Russian and British zones of influence before the First World War.

This depends, of course, on the four-months-old Russian-Turkish understanding continuing. Not all Russian observers are confident that it will. The red line which it seems Turkish forces must not cross is Al-Bab, the strategic town currently occupied by IS 55km to the north of Aleppo. Turkey struck this week at PYD forces close to Al-Bab, frustrating possible Kurdish moves to gain the upper hand there.

Some of Erdogan’s supporters, particularly the Turkish affiliates of the Muslim Brotherhood and other conservatives, have been urging him ever since August to move on Al-Bab, and speeches he has given suggest he is warm towards the idea. “They tell us not to go to Al-Bab, but we are obliged to go down there,” he said in a speech at Bursa on 22 October.

Deal on Aleppo

If – and it is a big "if" because such a move looks dangerous in military terms – Turkish allies and perhaps even its troops do move towards Aleppo, Turkey’s relations with Russia will come under serious strain. Putin needs to find some sort of deal over the city giving Turkey’s public the impression of at least a token gain.

Turkey has however shown willingness to respect Russian sensitivities in Aleppo by agreeing to remove al-Nusra Front militants from the town in a telephone conversation between Erdogan and Putin. The partnership with Russia looks like a way for Turkey to achieve a slightly scaled down version of its long-term policy aims in Syria, something the US could not provide.

On 23 October, Erdogan told the Russian TV channel Rossiya-1: “I need the support of my respected and valuable friend Putin in the joint struggle against terrorism in this region. We are ready to take every step necessary to cooperate with Russia in this area.” Russian-Turkish friendship is new but it may be more than a short-lived marriage of convenience.

- David Barchard has worked in Turkey as a journalist, consultant, and university teacher. He writes regularly on Turkish society, politics, and history, and is currently finishing a book on the Ottoman Empire in the 19th century.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

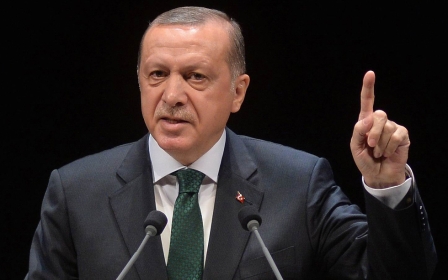

Photo: Russian President Vladimir Putin (L) shakes hand with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan (R) during a press conference on 10 October 2016 in Istanbul. (AFP)

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].