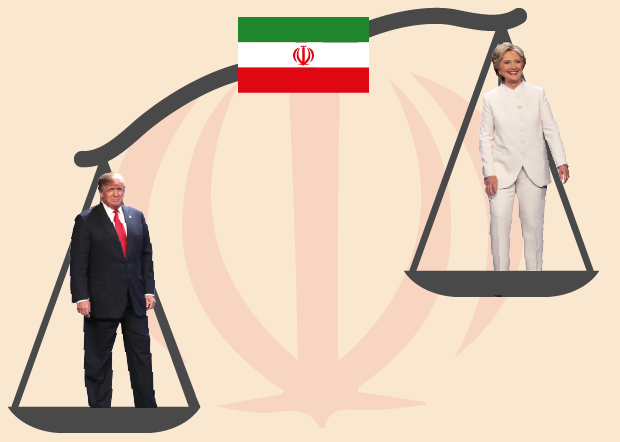

Why Iranians are quietly rooting for Trump

As one of the most acrimonious US presidential campaigns in living memory draws to a close, major powers around the world – with the obvious exception of Russia – appear to be banking on or even praying for a Hillary Clinton victory.

Trump’s nationalism and apparent reluctance to support international defence and security organisations, notably NATO, is music to the ears of Iranian defence and security strategists

Like Russia, Iran could also be considered an exception judging from the position of the country’s leader Ayatollah Seyed Ali Khamenei who, in a recent speech, appeared to favour Donald Trump on the grounds of his outspokenness and willingness to tell the truth.

But on this issue, like all aspects of foreign policy, the Iranian position is complex and nuanced and ultimately shaped more by institutional processes than public pronouncements by the country’s leaders.

There are good reasons why Iran would want a Trump victory. On the world stage, even a modest US withdrawal from global affairs is welcomed by the Iranian establishment.

And specifically on US-Iranian relations, putting aside Trump’s stated opposition to the nuclear deal which he called "one of the worst deals ever made by any country in history", the Republican candidate is seen as potentially more easy to deal with overall than Clinton would be.

Republicans seen as better deal makers

Iranian attitudes to US elections are primarily shaped by the experience of the Iranian revolution and its immediate aftermath. At the time, Democrat Jimmy Carter was in direct confrontation with Iranian revolutionaries epitomised by the long-running American embassy hostage crisis.

The prevailing view in Tehran appears to be that the worst and most dangerous moments in US-Iranian relations have passed

The resolution of that crisis on the eve of Republican Ronald Reagan’s presidency in January 1981 gave rise to an enduring perception in Tehran that deals are made more easily with Republicans as opposed to Democrats. For 35 years, Iranian leaders have consistently expressed this sentiment to varying degrees.

Despite strong opposition in Tehran (and Washington) to building on the deal's momentum and posturing by Trump and the wider Republican party, there is also a strongly held view that the nuclear deal cannot be easily undone. Indeed, if allowed to mature, the nuclear deal may form a template for a broader Iranian-American rapprochement, albeit one in the distant future.

Based on this fundamental assumption, the prevailing view in Tehran appears to be that the worst and most dangerous moments in US-Iranian relations have passed and the years ahead will likely be marked by a painfully slow process of qualified engagements and piecemeal understandings.

To that end, Iranian attitudes to the next US president will be shaped largely by the extent to which she or he can create distance between US policy in the Middle East and that of her allies (and Iran’s opponents), notably Israel and Saudi Arabia.

While both candidates unsurprisingly express effusive support for Israel, it is Hillary Clinton’s strong ties to Saudi Arabia which causes most concern in Tehran.

A freer hand?

At the leadership level, it is tempting to decipher a difference between Ayatollah Khamenei and President Hassan Rouhani on who they favour to become the next US president. In contrast to Khamenei, Rouhani has refrained from wading in too deeply, instead proclaiming the choice to be between “bad to worse or worse to bad”.

But in reality, the current geopolitical dynamics make the staunchly nationalist and isolationist Donald Trump the clear choice for Iranian leaders.

At an ideological level, the Islamic Republic has no issues with a nationalist USA enjoying its own culture. Instead, it is America’s overbearing foreign policy and specifically its over-reach and shameless double standards in the Middle East, which inform Iranian anti-Americanism.

The geopolitical calculus underpinning a qualified preference for Trump is reflected in the positions of the country’s core foreign policy establishments.

For example, the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps’ semi-official news agency has just published a detailed Trump-leaning essay, arguing that the elections, issues and drama surrounding it represent an “awakening” in American politics.

In light of Trump’s praise for Russian leader Vladimir Putin and specifically the latter’s decisive intervention in Syria at the expense of myriad rebel and jihadist groups, a Trump presidency will effectively allow Russia – and by extension Iran – to dictate the terms of the Syrian conflict’s conclusion.

On the other hand, Hillary Clinton will likely prolong the conflict by intensifying direct American intervention on the ground and by increasing American support to militant organisations.

For Iran, the difference in approach is critical. The Syrian conflict is a massive drain on resources and an intensification of American involvement, while not necessarily altering the outcome, will at a very minimum cost significantly more Iranian lives and treasure.

More broadly, Trump’s nationalism and apparent reluctance to support international defence and security organisations, notably NATO, is music to the ears of Iranian defence and security strategists.

If Trump’s vision is translated into coherent US policies, then the Islamic Republic has a freer hand in shaping events across the Middle East and devising a new regional security architecture on its own terms.

Furthermore, even the most qualified US withdrawal from its international commitments presents Iran with an opportunity to engage more boldly and robustly with key planks of the international community, notably the European Union.

- Mahan Abedin is an analyst of Iranian politics. He is the director of the research group Dysart Consulting.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Art by MEE infographics

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].