The Muslim Brotherhood: Time for renewal

With the Muslim Brotherhood’s fortunes going from bad to worse, there has been growing talk that the movement may be seeking some sort of reconciliation with the Egyptian regime.

Playing the long game and clinging onto legitimacy is a major gamble which so far does not appear to be paying off

This talk has been prompted in part by comments made in November by the Brotherhood’s Deputy Supreme Guide, Ibrahim Mounir, who told the Arabi 21 newspaper, “Let the wise men among our people, or the wise men of the world draw up a clear picture of reconciliation for us and we will react to it.”

Mounir’s words provoked a string of rumours about alleged secret reconciliation deals being brokered between the regime and the Brotherhood, including one involving purported Saudi sponsorship.

The media fall-out from all this clearly unsettled the Brotherhood, which moved quickly to quash the rumours. Mounir told the Al-Watan channel on 20 November, “We have never and will never reconcile with this military coup regime.”

The movement also issued a statement denying all “false news” about reconciliation and confirming its commitment to, “No reconciliation with the murderers, no compromise on legitimacy, and no compromise on the rights of the martyrs, the wounded and detainees.”

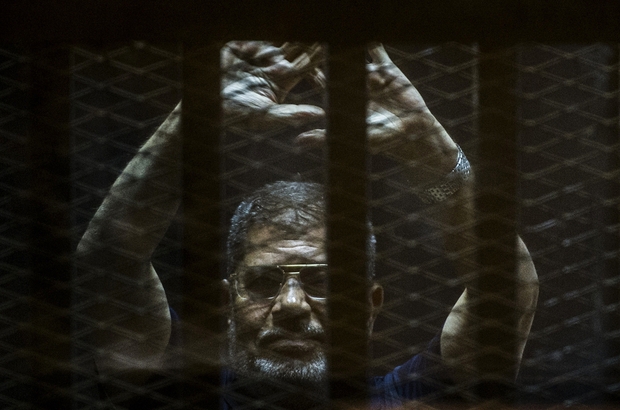

Indeed, the Brotherhood was at pains to reiterate the stance it has maintained since President Mohamed Morsi was toppled by the Egyptian military in July 2013, namely to sit it out and wait in the hopes that President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s regime will collapse, enabling it to step back into the breach.

READ MORE: The Muslim Brotherhood in the Emirates: Anatomy of a crackdown

Yet one wonders how long the Brotherhood can uphold this wait-and-see approach. Playing the long game and clinging onto legitimacy, as if taking the moral high ground will somehow carry it through the worst period of repression in its long history, is a major gamble, which so far does not appear to be paying off.

Rather, the movement is looking increasingly cornered and the pressures are mounting on every side.

External pressures

The election of Donald Trump to the US presidency is a case in point. It isn’t clear yet whether Trump will go as far as to sign a bill designating the Brotherhood as a terrorist organisation, something suggested by the president elect’s foreign policy advisor, Walid Phares.

But either way, Trump’s overtly anti-Islamist stance can only be bad news for the movement. Trump’s election has certainly given Sisi, who notably was the first foreign leader to congratulate the president-elect after his election victory, a boost. Trump is alleged to have referred to Sisi recently as a “fantastic guy” who “took control of Egypt” and “took the terrorists out”.

This comes on the back of the Brotherhood’s ongoing difficulties in the UK, long an important centre for the movement. The UK government’s controversial Muslim Brotherhood Review of 2015 may not have gone as far as to castigate the Brotherhood as a terrorist organisation, but it was damning nonetheless.

The report concluded that membership of the movement was a “possible indicator of extremism” and that “aspects of Muslim Brotherhood ideology and tactics” were contrary to UK values, national interests and national security.

It is true that at the end of October, the UK Parliament’s Foreign Affairs Select Committee issued a report on political Islam that criticised the government review. This report prompted an Egyptian parliamentary delegation to travel to London to warn British MPs of the error of their ways.

Notably, however, the British government has not changed its position towards the Muslim Brotherhood, leaving it feeling constrained and under pressure.

On the regional level, the Brotherhood is still smarting from the hard line taken against it by both Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, which have been uncompromising in their approach.

Meanwhile, while Turkey, and to a lesser extent Qatar, have proven to be solid allies, it is becoming increasingly apparent that reliance on these powers is not sufficient to guarantee the movement’s survival.

Internal difficulties

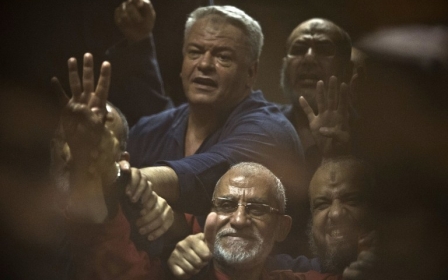

As if that weren’t enough, internal pressures are also heaping up. As well as trying to hold itself together with most of its leadership abroad or in prison, the Brotherhood is struggling to contain some of its youth, who are calling for a more confrontational approach towards the regime.

Mounir acknowledged as much when he told Al-Jazeera in November that the current divisions within the movement are being caused by a minority who do not subscribe to the Brotherhood’s general principle that “peacefulness is stronger than bullets”.

With most of its leadership abroad or in prison, the Brotherhood is struggling to contain some of its youth

Although the movement has been able to restrain these more ardent activists thus far, how long it will be able to do so is open to question, especially as its cadres continue to be chased down and rounded up.

In such an environment, it is little wonder that the movement has been unable to capitalise on Sisi’s mounting difficulties. This includes the recent ‘Revolution of the Poor’ campaign that was meant to see widespread public protests against the regime on 11 November, but which failed to materialise.

The Brotherhood’s inability to harness this public discontent is linked in part to the fact that while it may have engaged in charitable work as a means of expanding its influence, its ideology has never centred on championing the poor or seeking the redress of social inequality. However, it is also because the movement has been so crushed that it simply does not have the force to act.

Despite its calls for continued peaceful protests and a return to legitimacy, therefore, the Brotherhood is looking more and more like a spent force that is at risk of becoming increasingly irrelevant.

Yet it is caught between a rock and a hard place. While it is desperate to get back to Egypt, it knows that, even if the regime were open to reconciliation, going down such a route would inevitably entail making unpalatable compromises that could leave the movement weakened indefinitely. It would also leave it open to accusations that it had sold out on the thousands who sacrificed themselves for the cause, whether through death or imprisonment.

Separating politics and religion?

In a bid to turn the movement’s fortunes around, some leading brothers have renewed their calls for the Brotherhood to change its approach and separate out its political work from its traditional religious activities.

Former minister in Morsi’s government, Amr Darrag declared earlier this year, “We have to have a separation between what is dawa [preaching] and what is politics.” Others inside the movement have gone further, suggesting that the Brotherhood should reduce its political activities and focus on the religious arena.

Brotherhood member, Difrawi Nasif, reportedly explained, “We have to go back to our old methods and roots and concentrate on building up our dawa. We got too involved in politics.”

Such debates are nothing new and have been ongoing inside the movement for years. Ironically, prior to the 2011 revolution, those who favoured a retreat from politics in favour of prioritising dawa had come to the fore of the movement, in what was largely a disillusioned response to the movement’s failure to make any real political progress during the Mubarak era. The Brotherhood’s dismal experience in power following the 2011 revolution has clearly prompted some brothers to return to this stance.

'We have to go back to our old methods and roots and concentrate on building up our preaching, we got too involved in politics'

- Brotherhood member Difrawi Nasif

However, these latest calls have also been influenced by the Tunisian Islamist movement, Ennahda, which although not part of the global Muslim Brotherhood movement, is from the same ideological stable.

In May 2016, Ennahda announced that it was separating its political and religious work, proclaiming that it was no longer a party engaged in the struggle for identity but now considered itself as a “national democratic party”.

While this decision appears to have been more about rebranding than any deep-seated ideological shift, with the separation between politics and dawa being more procedural than anything else, it was also a clear attempt by Ennahda to prove to both an internal and an external audience that it is able to transcend the politics of identity and be a modern civic party that can represent the interests and aspirations of today’s Tunisians.

The attractions of such an approach are evident. Yet there are several factors that make it far easier for Ennahda to go down this path than its counterparts in Egypt. Firstly, unlike the Egyptian Brotherhood, Ennahda is not burdened by being the spiritual centre of a global movement that has put the combination of politics and Islam at the core of its ideology. It therefore has a greater freedom to forge its own path than the ‘mother branch’ that is more bound by its traditions.

Secondly, under successive Tunisian regimes, Ennahda was never given anything like the space afforded to the Egyptian Brotherhood to engage in grassroots activism. As a result Ennahda has always been far more engaged in politics than dawa, and its leaders have always seemed more like politicians than imams. The same cannot be said of the Egyptian brothers. One of the criticisms thrown at the Egyptian Brotherhood during its time in power was that its political leaders, including Morsi, appeared more comfortable addressing the crowds in mosques than at political rallies.

Furthermore, while Ennahda managed to come through its experience in power bruised but still intact, the Brotherhood’s attempt at "doing politics" was nothing short of an unmitigated disaster. Despite being the standard bearer of "political Islam", when it came to power the Brotherhood’s politics, as well as its political vision, turned out to be hollow, built on slogans and vague notions that could not be translated into practice. By consequence, the movement very quickly fell back on reactive policymaking and mass mobilisation, fuelling the perception that it simply wasn’t up to the job.

Thus, while separating out politics from dawa was almost a natural transition for Ennahda, it is surely impossible for the Egyptian Brotherhood to do the same. Moreover, the Egyptian movement’s strength has always derived from its combination of being both a political actor and a socio-religious movement at the same time.

Can the Brotherhood save itself?

Yet the Brotherhood has to do something if it is to save itself. Although it can always rely on its core support base, who will back it regardless of the choices it makes, if it wants to move beyond the current impasse and find a way to return to Egypt without being comprised, it needs to find a way to reform from within. This means going beyond the usual talk of engaging in reviews, and requires rethinking what the Brotherhood is and what it stands for.

Neither the regime nor the Brotherhood appears ready to reform in any meaningful sense and so Egypt looks set to be in for a prolonged period of uncertainty and instability

This is not going to be easy. Like many authoritarian entities, the Brotherhood has never been a movement inclined to reform or self-review. Moreover, trying to implement any kind of serious reform in such a toxic environment is challenging at best.

In addition, the movement is crying out for leadership. As high-ranking former Brotherhood member Ibrahim Zafarani commented recently, “The current leadership is helpless. It is living through a major decision-making crisis. Difficult decisions require a leadership that is commensurate with the enormity of the situation.”

But perhaps most important of all, reform inevitably carries its own risks. As a movement that has always preferred the realm of generalities and that has sought to be all things to all men, pinning down a concrete reform plan could see the Brotherhood unravel. The Brotherhood is well aware that real reform could turn out to be just as risky as sitting it out and waiting for its opponents to fall.

The tragedy for Egypt in all this is that if the Brotherhood fails to reinvent itself, the country looks destined to remain forever locked in the same old battle between the two staid forces of the past – the regime on one side and the Brotherhood on the other.

Indeed, more than five years on from the 25th January revolution and there is still no alternative to these two old powers. Given that neither the regime nor the Brotherhood appears ready to reform in any meaningful sense, Egypt looks set to be in for a prolonged period of uncertainty and instability.

- Alison Pargeter is a North Africa and Middle East expert with a particular focus on Libya, Tunisia and Iraq, as well as on political Islamist movements. She is a senior research associate at the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), a senior associate at global consultancy firm, Menas Associates, and a Visiting Senior Research Fellow in the Department of War Studies at Kings College London. Her books include Return to the Shadows: The Muslim Brotherhood and An-Nahda since the Arab Spring (Saqi, 2016); Libya: The Rise and Fall of Qaddafi (Yale University Press, 2012); The Muslim Brotherhood: The Burden of Tradition (Saqi 2010 (updated edition 2013); and The New Frontiers of Jihad: Radical Islam in Europe (I.B .Tauris 2008).

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: Demonstrations staged across Egypt to protest the military take-over since July 2013 continue (Anadolu Agency)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].