The struggle of refugee mothers stranded in Greece

ATHENS, Greece - In 2015, over one million refugees from war torn countries including Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan arrived on Europe’s doorstep after having crossed the Mediterranean and Aegean seas in overcrowded, flimsy boats and dinghies.

Most of those who landed on Greek shores throughout 2015 and the early months of 2016 moved onwards into central Europe within weeks of their arrival. Some 50,000, however, found themselves unexpectedly stranded in Greece after the EU struck a deal with Turkey in March 2016. The border with Macedonia - the most popular land route to central Europe - was slammed shut soon thereafter.

Despite the deteriorating conditions in camps across Greece, and the increasingly poor treatment of refugees throughout Europe, refugees continue to trickle in through the Greek islands on a near-daily basis. With the Macedonian border closed, Greece is struggling under the weight of increasingly desperate refugees and migrants.

“Earlier this year, there were several changes in and around Greece on asylum and migration routes, including the closure in the north and stricter border control from Turkey,” explains Roland Schoenbauer, spokesman for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

This, in turn, led “to some 50,000 refugees and migrants being stranded in Greece - a country that has not been prepared for accommodating such a large number of men, women and children and whose asylum authorities have been overwhelmed with issues like registration and processing asylum claims,” Schoenbauer continued.

Approximately two-thirds of the stranded refugees languishing in camps and shelters across Greece are women and children - the most vulnerable, according to Schoenbauer.

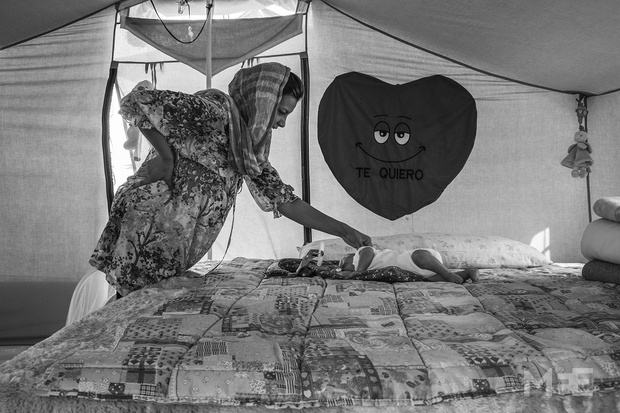

They are women like Aria Taheri, a 23-year-old Afghan who gave birth to her first child in a camp in Oinofyta, a small town on the outskirts of Athens. Taheri left Afghanistan in early 2016 with her husband and his family after they had been targeted by the Taliban for her husband’s work as an independent contractor with the US military. She was three months pregnant.

Like most of the incoming refugees in early 2016, Taheri and her family intended to keep moving until they reached central Europe, where she hoped to give birth. But, with the ratification of the EU-Turkey deal on 20 March and the closure of the border with Macedonia soon thereafter, Taheri and her family were stranded in Athens mid-journey. They reached their destination on 4 April 2016.

Taheri's story is much like thousands of others, mostly Afghan refugees now languishing in camps across the country.

Motherhood as a refugee is a unique struggle with which a large percentage of the current refugee population in Greece is burdened. Protecting their children from physical harm is only one small aspect of the incredible responsibility refugee mothers face.

“It’s a big responsibility for me,” said Maryam Sheikh Mohammed, a Kurdish mother of four from Syria who made the journey earlier this year with her husband and four small children. “I worry about their health. I don’t worry about mine, I only care about my children,” she continued while she struggled to feed them dinner one night at the City Plaza Hotel in central Athens.

The abandoned hotel was occupied by leftists nearly one year ago and has since been home to 400 refugees from Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan.

But Afghans are not the only ones whose lives are in limbo. With the overburdened registration and asylum processing system in Greece, many Syrians, Kurds and Iraqis also find themselves waiting indefinitely, with little information to help them cope with their situation.

Dania Kasem, a Syrian refugee from Damascus, arrived in Greece in early 2016 with her three-year-old son, Amar. She immediately began the family reunification process, but was told it could take upwards of one year to be reunited with her husband in Germany.

For eight months she waited, without a single update, for her case to be processed. “My son understands the situation, and he’s always asking when he will go meet his father; when he will get on a plane and go to Germany,” Kasem explained over sweet Syrian coffee in her room at the City Plaza Hotel.

In early December, nearly one year after starting the family reunification process, Kasem received word that she and her son would be able to join her husband in the new year. Kasem is Syrian and therefore considered one of the lucky ones, as Afghan asylum seekers are increasingly being rejected and sent back to their homeland.

Giving birth in a camp

The psychological aspect of caring for children and protecting them from harm - both physical and emotional - is an aspect of the refugee experience that is only now coming to light as more and more mothers remain stranded for months on end in deteriorating camps, and more women are giving birth, sometimes for the first time, in these camps.

But for some refugee mothers, it is too little too late. For Aziza Alizade, a slight 21-year-old woman from the Ghazni province in Afghanistan, being stuck in a makeshift camp at the Piraeus Port in central Athens for several months over the brutal Greek summer led to a miscarriage.

“It’s so painful for me,” she said as tears rolled down her cheeks. “I escaped from the Talib[an] in Afghanistan and we came here to have a safe and comfortable life, but we came here and we lost our baby.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].