2017: A year to recall three bleak Palestinian anniversaries

Increasingly, Palestinians seem doomed to become subjects, or at best second-class citizens, in their homeland. Israeli expansionism, United States unconditional support, and UN impotence are combining to create dismal prospects for Palestinian self-determination and for a negotiated peace that is sensitive to the rights and grievances of both Palestinians and Jews.

Recalling three notable anniversaries to be observed in 2017 may help us understand better how this distressing Palestinian narrative unfolded over the course of the past 100 years.

Perhaps such remembrances might even encourage the rectification of past failures, and encourage flagging efforts to find a way forward even at this belated hour. The most promising initiatives are now associated with a growing global solidarity movement dedicated to achieving a just peace for both peoples.

For now, neither the United Nations nor traditional diplomacy seem to have much leverage over the play of social and political forces that lies at the core of the Palestinian struggle. Only the nonviolent resistance of Palestinians to their prolonged ordeal of occupation and transnational civil society militancy seem to have any capacity to exert positive leverage over the status quo and to sustain hope.

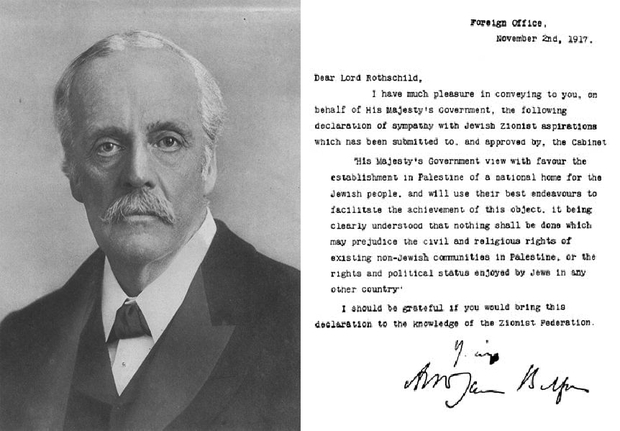

On 2 November 1917 the British foreign secretary, Arthur Balfour, was persuaded to send a letter to Baron Lionel Rothschild, a leading Zionist advocate in Britain, expressing support for the aspirations of the movement. The key language of the letter is as follows:

"His Majesty's Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use its best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country."

An obvious initial observation is why was Britain moved to take such initiative in the midst of World War One. The most immediate explanation is that the war was not going so well, nurturing the belief and hope by British leaders that siding with the Zionist movement would encourage Jews throughout Europe to back the Allied cause, especially in Russia and Germany.

A second motivation was to further British interests in Palestine, which Lloyd George, then prime minister, regarded as strategically vital to protect the overland trade route to India as well as safeguard access to the Suez Canal.

The Balfour Declaration was controversial from the day of issuance, even among some Jews. For one thing, such a commitment by the British Foreign Office was a purely colonialist undertaking without the slightest effort to consider the sentiments of the predominantly Arab population living in Palestine at the time (Jews were less than 10 percent of the population in 1917) or to take account of rising international support for a right of self-determination enjoyed by all peoples.

Jewish opposition to Balfour

Prominent Jews, led by Edward Montagu, secretary of state for India at the time, opposed the declaration, fearing that it would fan the flames of anti-Semitism, especially in the cities of Europe and North America.

Beyond this, the Arabs felt betrayed as Balfour’s initiative was seen both as breaking wartime promises to the Arabs of postwar political independence in exchange for joining the fight against the Turks. It also signalled future troubles arising between the Zionist promotion of Jewish immigration to Palestine and the agitation of the indigenous Arab population.

It should be acknowledged that even Zionist leaders were not altogether happy with the Balfour Declaration. There were deliberate ambiguities embedded in its language. For instance, Zionists would have preferred the word "the" rather than "a" to precede "national home". Also, the pledge to protect the status quo of non-Jews was seen as inviting trouble in the future, although as it turned out, this assumption of colonialist responsibility was never acted upon.

And finally, the Zionists received support for a national home, not a sovereign state, although backroom British talk agreed that a Jewish state might emerge in the future, but only after Jews became a majority in Palestine.

It is worth this backward glance at the Balfour Declaration to realise how colonial ambition morphed into liberal guilt and humanitarian empathy for the plight of European Jews after World War II, while creating an unending nightmare of disappointment and oppression for the Palestinian population.

After World War Two, with strife in Palestine rising to intense levels, and the British Empire in free fall, Britain relinquished its mandatory role and gave the fledgling UN the job of deciding what to do.

The UN created a high level group to shape a proposal, resulting in a set of recommendations that featured the partition of Palestine into two communities, one for Jews, the other for Arabs. Jerusalem was internationalised with neither community exercising governing authority nor entitled to claim the city as part of its national identity. The UN report was adopted as an official proposal in the form of General Assembly Resolution 181.

The Zionist movement accepted 181, while the Arab governments and the representatives of the Palestinian people rejected it, claiming it encroached upon rights of self-determination and was grossly unfair. At the time, Jews formed less than 35 percent of the population yet were given more than 55 percent of the land.

As is widely appreciated, a war ensued, with armies of neighboring Arab countries entering Palestine being defeated by well trained and armed Zionist militias. Israel won the war, ending with control over 78 percent of Palestine at the time an armistice was reached, dispossessing over 700,000 Palestinians, and destroying several hundred Palestinian villages. This experience is the darkest hour experienced by the Palestinians, known among them as the nakba, or catastrophe.

The third anniversary of 2017 is that associated with the 1967 war, which led to another military defeat of Arab neighbours, and the Israeli occupation of the whole of Palestine, including the entire city of Jerusalem and the Gaza Strip.

US strategic partner

The Israeli victory changed the strategic equation dramatically. Israel that had been previously viewed as a strategic burden for the United States suddenly was appreciated as a strategic partner entitled to unconditional geopolitical support.

In the famous Resolution 242, the UN Security Council unanimously decided on 22 November 1967 that the withdrawal of Israeli forces should be negotiated, with certain agreed border modifications, in the context of reaching a peace agreement that included a fair resolution of the dispute pertaining to Palestinian refugees living throughout the region.

During the next 50 years we have come to realise that 242 has not been implemented. On the contrary, Israel has further encroached on Occupied Palestine through its extensive settlements and related infrastructure, and the point reached where few believe that an independent Palestinian state co-existing with Israel is any longer feasible or even desirable.

It is too late to reverse altogether these strong currents of history, but the challenge remains acute to find a humane outcome that somehow allows these two peoples to live together or in separated political communities.

Let’s fervently hope that a satisfactory solution is found before another anniversary commands our attention.

- Richard Falk is an international law and international relations scholar who taught at Princeton University for 40 years. In 2008 he was also appointed by the UN to serve a six-year term as the Special Rapporteur on Palestinian human rights.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: A Palestinian national flag is seen flying past Israeli soldiers during a march marking the Palestinian day of independence in Hebron, West Bank, on 15 November, 2016 (AFP)

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].