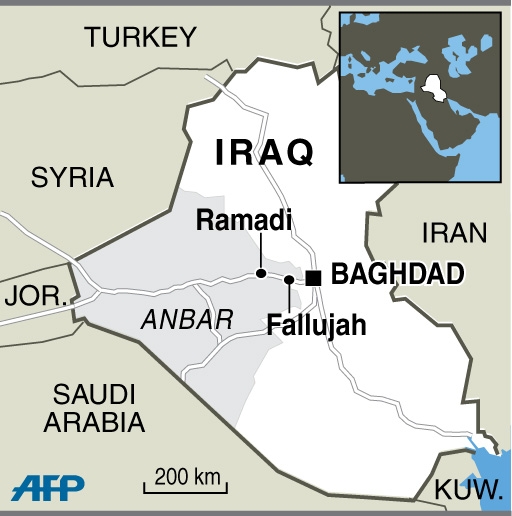

Could Iraq’s elections help end the Anbar crisis?

When protests began in Iraq's western province of al-Anbar in late 2012, the main demands of the mainly Sunni demonstrators appeared easily within reach of the Shiite-dominated government of Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki.

Sparked by anger over what demonstrators saw as politically motivated arrests of a former finance minister’s bodyguards, the protests evolved into an outcry for better services for the province and more political rights for Iraq's Arab Sunnis in general.

Maliki's refusal to look seriously into these demands had three major consequences: firstly, the protest movement widened to attract support from other provinces; secondly, it helped to fuel a vicious al-Qaeda styled militancy in an already troubled country; and thirdly, supporters of the government then began viewing the whole protest movement, and by extension those who sympathised with it, as a "terrorist enemy" - further fuelling sectarian tensions.

These problems were then compounded when Maliki ordered an army offensive against Anbar last December, with civilians caught in the crossfire and reports that pro-government militias were taking part. Terror attacks carried by anti-government militants across the country deepened tensions.

While many observers saw Maliki's offensive as a bid to rally support before the parliamentary elections, it is now appearing more likely that it will now destabilise his ruling State of Law Coalition. Many who once backed him are now amongst his fiercest critics. The parliamentary bloc affiliated with influential Shiite cleric Muqtada al-Sadr -whose backing in 2010 that gave Maliki the parliamentary numbers needed to form a government - has already indicated that they would not be joining him again.

New parliamentary hopefuls are now promising to try to reverse Maliki's policies in Anbar should they be elected. These included Shiites who are neither affiliated with the Sadr movement nor the Iraqiya bloc of former prime minister Iyad Allawi, which in 2010 secured more seats than Maliki's party but failed to form a coalition government.

One such candidate, Safwan al-Hassani, believes that only a change of government can solve Iraq's current woes, including the crisis in Anbar. "You need some trust between the government and the people it's governing. Around of 70% of our problems todays cannot be resolved because the state lacks this vital trust," he told Middle East Eye. "Most of the people in Anbar would not accept dealing with Maliki's government after the blunders it made while tackling the security situation there," he added.

Hassani said the government did not listen to the advice of many of its allies when dealing with Anbar and lost control of what is happening in many of the province's cities as a result of Maliki's mismanagement. He noted that the government used army personnel composed of people from outside of Anbar, predominately from the south, which gave the impression that it was a sectarian war.

"We need to reassure our Sunni brothers that we are not targeting them but that they are our allies so that we can jointly fight terror and avoid a civil war that would not only eliminate what's left of democracy but also destroy the whole country as a whole," he stressed. "Had it made sincere efforts, the government could have resolved many of the grievances of Sunnis. Now there is talk of Sunni provinces wishing to break-away from the rest of Iraq," he warned.

Hassani's views on Anbar were similar to another parliamentary hopeful from another political camp, Nadeem Al-Abdalla, who proposed forming a national consensus - including the Sunnis - in what's going on in Anbar. "There should not be any military action in Anbar or an attack on any Iraqi city without consulting all of Iraq's political players or exhausting all peaceful routes of negotiation to address the origin of the problem," stressed Abdalla. He suggested forming what he called "provincial armed forces" that consist of "at least 90% of members drawn from the same province they serve".

Although he is running for the 2014 parliamentary elections, Abdalla blames the current political system for the country's instability. "What’s going on in Anbar is a reflection of the creation of Iraq’s political system after 2003, which has created political parties and blocs consisting of followers from one sect and/or ethnic origin," he noted. "It is clear that the Sunni population of Iraq feel that this system marginalises them and degrades them to the status of a second player in Iraqi politics, with no real involvement in decision-making functions," he added.

Abdalla sees the problems in Anbar as a consequence of the political map, adding that it became worse when security and financial powers became concentrated in the hands of the current prime minister. "In the political term of 2010-2014, we ended with a situation in which the Prime Minister and his office hold most of the power, particularly related to finance and the armed forces," he said.

Unlike Abdalla, who still sees a solution by working within the current political system, other observers believe that taking part in that process only reinforces its legitimacy. Dr Sabah al-Mokhtar, an Iraqi-born observer who heads the Arab Lawyers Association in London, dismissed the whole election process as a sham. "The sectarian constitution was put in place during the US occupation of Iraq; it cannot be viewed as democratic," he stressed. "Many are boycotting these theatrical elections, and many others [in Anbar] can't vote even if they wanted to because of the security situation there. In all cases, nothing is going to really change on the ground," he added.

From the view of Maliki supporters, however, the military offensive is seen as a straight forward anti-terror operation against a segment of the population that they view as unwilling to accept election results. They don't see a middle way to ending the crisis other than crushing the protest movement as well as the nationwide militancy. Otherwise, they too expect more of the same policies to continue.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].