The UK's century-long war against Yemen

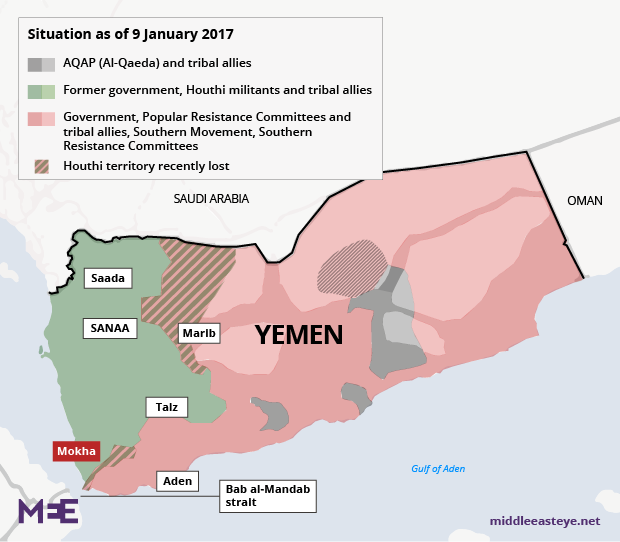

Britain is backing a Saudi invasion of Yemen that has cost thousands of innocent lives. It is providing advanced weaponry to the Saudis, training their military and has soldiers embedded with them, helping with targeting of air strikes.

Yemen is the sole country on the Arab peninsula with the potential power to challenge the colonial stitch-up reached between Britain and the Gulf monarchies it placed in power in the 19th century

This is true of today. But it also describes exactly what was happening during the 1960s, in a shameful episode which Britain has, like so much of its colonial past, effectively whitewashed out of history.

In 1962, following the death of Yemeni King Ahmad, Arab nationalist army officers led by Colonel Abdullah Al-Sallal seized power and declared a republic. The royalists launched an insurgency to reclaim power, backed by Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Israel and Britain, whilst Nasser’s Egypt sent troops to support the fledgling republican government.

READ War in Yemen: Why the UK should chair peace talks

In his book Unpeople, historian Mark Curtis pieces together Britain’s “dirty war” in Yemen between 1962 and 1969, using declassified files which – despite their public availability and the incendiary nature of their revelations - have only ever been examined by one other British historian. British involvement spanned both Conservative and Labour governments, and implicated leading members of the British government in war crimes.

Dirty war

At first, Britain’s role was primarily to support and equip Jordan’s involvement in the war. Just as today, it was British-supplied fighter jets carrying out airstrikes on Yemen, with British military advisers embedded with their allies at the most senior level. This involvement stepped up a gear in March 1963, however, when Britain began covertly supplying weapons to the royalist forces themselves via their Gulf allies.

What Britain wanted, Prime Minister Harold Macmillian said, was "a weak government in Yemen not able to make trouble”

The following month, says MI6 biographer Stephen Dorrill, millions of pounds worth of light weapons were shipped from an RAF station in Wiltshire to the insurgents, including 50,000 rifles. At the same time, a decision was taken by Britain’s foreign minister (shortly to become prime minister) Alec Douglas-Home, MI6 chief Dick White and SAS founder David Stirling to send a British force to work directly with the insurgents. But to avoid parliamentary scrutiny and public accountability, this force would be comprised of mercenaries, rather than serving soldiers.

SAS soldiers and paratroopers were given temporary leave to join this new force on a then handsome salary of £10,000 per year, paid for by the Saudi Prince Sultan. The same time as these decisions were taken, Douglas-Home told parliament that “our policy in Yemen is one of non-intervention in the affairs of that country. It is not therefore our policy to supply arms to the royalists in the Yemen”.Eddie Izzard: I was born in Yemen - its civil war shames us all

British officials also knew that their insurgency had no chance of winning. But this was not the point, for as Prime Minister Harold Macmillan told US President John Kennedy at the time: "I quite realise that the loyalists will probably not win in Yemen in the end but it would not suit us too badly if the new Yemeni regime were occupied with their own internal affairs during the next few years". What Britain wanted, he added, was "a weak government in Yemen not able to make trouble”.

Labour came to power in the autumn of 1964, but the policy stayed the same; indeed, direct (but covert) RAF bombing of Yemen began soon after. In addition, another private British military company Airwork Services, signed a $26 million contract to provide personnel for training Saudi pilots and ground crew involved in the war.

Secret bombing

This agreement later evolved into British pilots actually carrying out bombing missions themselves, with a foreign office memo dated March 1967 noting that “we have raised no objection to their being employed in operations, though we made it clear to the Saudis that we could not publicly acquiesce in any such arrangements”. By the time the war ended – with its inevitable Republican victory – an estimated 200,000 people had been killed.

Nor was this the first time Britain had aided and abetted a Saudi war against the Yemenis. In 1934, Ibn Saud invaded and annexed Asir - “a Yemeni province by all historical accounts” in the words of the academic and Yemen specialist Elham Manea – and forced Yemen to sign a treaty deferring their claims to the territory for 20 years. It has never been returned to Yemen and remains occupied by the Saudis to this day.

The sniper: How a Yemeni shopkeeper kills to 'liberate my city'

Britain’s role in facilitating this carve-up was significant.As Manea explains: “During this period, the real power was Great Britain. Its role was crucial in either exacerbating or containing regional conflicts… [and] in the Yemeni-Saudi war they intensified the conflict to the detriment of Yemen.”

When Ibn Saud claimed sovereignty over Asir in 1930, the British, who had been neutral towards disputes between the peninsula’s various rulers hitherto, “shifted their position, perceiving Asir as ‘part of Saudi Arabia’... This was a terrible setback for [Yemeni leader] Yihia and drove him into an agreement with the British in 1934 which ultimately sealed his total defeat.”

The third war

So the current British-Saudi war against Yemen is in fact the third in a century. But why is Britain so seemingly determined to see the country dismembered and its development sabotaged?

Strange as it may seem, the answer is that Britain is scared of Yemen, the sole country on the Arab peninsula with the potential power to challenge the colonial stitch-up reached between London and the Gulf monarchies it placed in power in the 19th century, and who continue to rule to this day.

A peaceful, united Yemen would threaten Saudi-British-US hegemony of the entire region

As Palestinian author Said Aburish has noted, the “nature of the Yemen was a challenge to the Saudis: It was a populous country with more than half the population of the whole Arabian peninsula, had a solid urban history and was more advanced than its new neighbour. It also represented a thorn in the side of British colonialism, a possible springboard for action against their control of Saudi Arabia and all the makeshift tributary sheikhdoms and emirates of the Gulf. In particular, the Yemen represented a threat to the British colonisation of Aden, a territory which considered itself part of a greater Yemen which had been dismembered by colonialism."

The potential power of a united, peaceful, Yemen was also highlighted by Kennedy Trevaskis, Aden’s High Commissioner in 1963-4, who noted that, if the Yemenis took Aden, "it would for the first time provide the Yemen with a large modern town and a port of international consequence" and "economically, it would offer the greatest advantages to so poor and ill developed a country".

A peaceful, united Yemen would threaten Saudi-British-US hegemony of the entire region. That is why Britain has, for more than 80 years, sought to keep it divided and warring.

Dan Glazebrook is a political writer specialising in Western foreign policy. He is author of Divide and Ruin: The West's Imperial Strategy in an Age of Crisis. He is currently crowdfunding to finance his second book.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Image: Smoke billows behind a building following a reported air strike by the Saudi-led coalition in the Yemeni capital Sanaa on 22 January, 2017. (AFP)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].