Sudan's honeymoon with US is over: Muslim ban 'worse than sanctions'

KHARTOUM - Sara el-Bashir was at a hospital in Florida getting ready to deliver her third baby, but she was adamant on sharing her painful story before going into labour.

Bashir was worried about her two other children, especially her six-year-old son Aboudi, who was supposed to be in her sister’s care while she delivered his sibling.

"I needed her with me, she is one of very few people that knows how to take care of Aboudi, my son. He has autism and I can't just leave him with anyone - neighbours and friends will find it difficult to deal with him," Bashir told Middle East Eye, before labour began.

'The real issue for me is that I was asked whether I am a Muslim and this took me by surprise'

Bashir is a 34-year-old chemical engineer who completed her degree at Sudan's University of Khartoum before moving to the US with her husband.

Barely 10 days days into his tenure as US president, President Trump signed an executive order that keeps nationals of seven Muslim-majority countries out of the US for 90 days, in an attempt to allegedly block "radical Islamic terrorists" from setting foot on American soil.

On 27 January, while Trump was signing this life-changing document, Bashir's sister Hind was on her way to the US. When she arrived in Orlando in the morning, she was interrogated by security officials and held in an office for six hours.

Peaceful or forceful deportation, your choice

She was able to send messages to Bashir informing her that she was being kept in an office and told that her visa had been revoked.

"She was told to voluntarily withdraw her visa and face peaceful deportation and she can re-apply again or else she would face forceful deportation, detention for one day and be banned for five years from entering the US," Bashir said.

Bashir's mother is not in good health and her sister was her only hope during this difficult time.

"I am now in the hospital and we are really struggling as my child cannot suddenly be put in a place he is unfamiliar with," said Bashir who also has a four-year-old daughter.

Hours after the arbitrary decision, airlines were already turning away Sudanese passengers on their way to the US.

"I was told by airport security that I can't board my flight to New York even though I had a valid visit visa," Ali said after she returned back to Khartoum.

Ali was trying to use the time during her semester break to help her sister in the US, who had no one else to support her, but she could not make it past her first transit.

"My sister is in severe need of help in the states, I was supposed to help her take care of her two children so she can take her exams. Her husband works 12-16 hours per day and she needs time to study," said Ali.

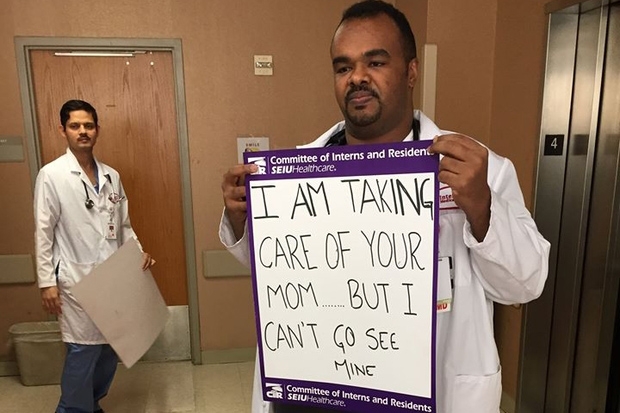

Her sister's dream is to become a doctor in the US, so she is studying to take her United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE). With no one to help take care of her children, she might have to postpone her exams for a few months and miss the opportunity to apply for a job this year, according to Ali.

Red flag

Even US citizens born in Sudan were affected by the ban.

Ahmed Kodouda, 28, was flying into Washington DC on the night of 29 January. A US citizen, who was born in Sudan and has been working overseas since 2013 with a non-governmental organisation focusing on conflict resolution.

"I went to [the airport] anticipating something would happen and I felt as if I did something wrong even though I did not. I was stopped for 30 minutes and interrogated by officers from the customs and border protection," said Kodouda.

'I went to [the airport] anticipating something would happen and I felt as if I did something wrong even though I did not'

Kodouda was escorted to a holding area where he was asked about the place of his birth. The fact that he was born in Sudan raised many questions during the interrogation, until he was allowed to pass through.

"The real issue for me is that I was asked whether I am a Muslim and this took me by surprise," said Kodouda in a phone interview from his home in Virginia state.

Kodouda's story raised a red flag for Sudanese-Americans. The situation was even worse for green-card holders who shared their struggles on social media after being stranded outside the US, not knowing where to head next.

On Sunday, the Trump administration backtracked on one of the main points of its new executive order, saying that green card holders would not be affected by the new rules. This happened after many US residents were stopped and held for many hours at airports on Friday and Saturday.

In his last days in office, former president Barack Obama lifted a US trade embargo that was imposed on Sudan for almost 20 years, through an executive order.

This meant that Sudan would finally be able to receive imported goods and services from the US. Sudan has been subject to a US trade embargo since 1997 for its alleged support for militant groups.

'What happened now is worse than the sanctions; as businessmen we were hoping to start doing business in the US, but now we can’t even travel freely'

The US saw this as a critical move for regional security, in exchange for Sudan taking several measures including putting an end to its support for rebels in neighbouring South Sudan, cooperating with American intelligence agents and improving access to aid groups.

The Sudanese people expected that this step would improve the rapidly deteriorating economy.

"When the US announced the lifting of sanctions, the value of the Sudanese pound to the dollar in the black market dropped from 19.3 to 15 Sudanese pounds, which is a huge reduction and this is because there was optimism that lifting of the embargo will encourage foreign investment and trade," said a businessman who wanted to remain anonymous because he works in the black market for currency exchange in his shop in al-Riyadh, an upper-scale neighbourhood in Khartoum.

The honeymoon with the US was short-lived: just two weeks later President Trump issued his executive order that mainly affects ordinary Sudanese people, as the ban does not extend to diplomats and government officials.

“What happened now is worse than the sanctions; as businessmen we were hoping to start doing business in the US, but now we can’t even travel freely,” he said.

The US Embassy in Khartoum has already informed the public through its website and Facebook page that all visa scheduling and appointments have been suspended, except for official visits.

Dr Sami Abdel-Haleem, a Sudanese-American currently living in Sudan and teaching law at a number of universities there, said that he expected President Trump was going to do something like this.

Abdel-Haleem's wife and three daughters who are also US citizens live in the US and he visits them every few months.

"Even as a US citizen, I imagine that entering the US to visit my family will not be as easy as before. I will not be 100 percent certain from now on when I fly into the US that I will be allowed in," he said.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].