Advice for the Syrian opposition: Make a deal with Russia to curb Iran

Russia has dealt its cards masterfully in Syria. By supporting the regime of President Bashar Assad, which was on the brink of unravelling prior to Moscow’s military deployment in September 2015, it allowed the government and allied forces to regain control of Syria’s largest urban centres.

Russian leverage on the Syrian military scene and the fact that, unlike Iran, it has limited objectives in Syria, make it an unavoidable interlocutor for the Syrian opposition and their Arab backers.

Moscow is there for the long run and is the only force capable of containing Iran’s ambitions in Syria. So for the opposition, learning to work with Russia on Syria – whether in Astana or Geneva or elsewhere - is necessary.

Diplomacy as a weapon

With a few astute moves, Russia has been able to strike big in Syria. Relying on an annual budget of less than $2bn and minimal deployment on the ground, estimated at around 4,000 men, Moscow has turned Assad’s massive losses into gains.

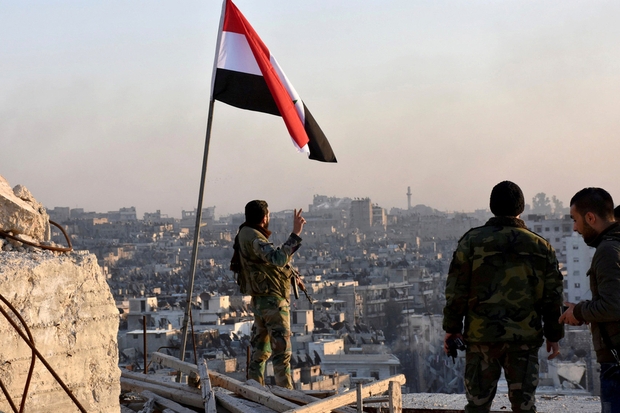

It first put an end to rebel advances on Assad’s seat of power, around the coastal Syrian area, in the fall of 2015. Then it provided significant air coverage, allowing pro-regime forces to regain territory around Damascus, Homs and Hama and, finally, Aleppo.

The fall of Aleppo, once Syria’s most populous city, cannot be attributed alone to Russian air power, but also to diplomatic capabilities

Russia has supported the demographic changes in the country engineered by Iran and the regime, by facilitating agreements that have allowed besieged rebels to leave for the north of the country.

This tactic has not only rid the regime of opposition forces located in strategic urban regions, but also led to feuds between rebel factions competing for the control of smaller geographical areas north of Aleppo.

Yet the fall of Aleppo, once Syria’s most populous city, cannot be attributed alone to Russian air power, but also to diplomatic capabilities.

According to the testimony of one Hezbollah fighter whom I spoke with on condition of anonymity, there was no real battle to speak of in Aleppo because of the Russian-Iranian-Turkish deal.

In Aleppo, Russia succeeded in neutralising the Syrian opposition’s most important backer, Turkey. In exchange for the capture of the city, Moscow offered Ankara the chance to deploy forces alongside its borders with Syria, which has greatly hindered the progress of the Syrian Kurds, Turkey’s longtime foe.

UN shifts language on Syrian 'political transition' in concession to Assad

The continued advance of the Turkish-backed Euphrates Shield in the Al-Bab region stalls the Kurdi

Moscow also managed to bring Ankara on board for a tripartite peace negotiations on Syria in Astana, a move that has left the opposition isolated and weakened by excluding their Arab and Western backers from the political equation.

This increased weakness does not leave the Syrian opposition, or their backers - who appear to have diverted their attention from Syria to a conflict closer to home like Yemen - with many choices, but to seriously work on a deal with Russia, at any cost.

The unavoidable interlocutor

While Russia has proven to be a duplicitous interlocutor in Syria, its objectives are more flexible than Iran’s, namely in how it perceives the opposition forces, the future composition of the Syria state and the future of President Assad.

“Russia is more flexible on most of these matters simply because the nature of its regional interests and the domestic-security facet they entail is way different from that of Iran,” says Max Suchkov, an expert with the Russian International Affairs Council, a Moscow-based think tank.

While Russia wants to consolidate power with Assad, Iran prefers a weak Syrian leader that it can better control.

Such a force in Syria could provide Tehran with long-term leverage on the regime - if it was sustainable.

“The Syrian demographics will make the unfolding of a lasting and local PMU-type [force] in Syria much harder for Iran,” says Alex Vatanka, a senior fellow at the Middle East Institute in Washington, DC.

Suchkov underlines that Russia is extremely committed to finding a political solution to the conflict. “There is a feeling of 'Syria fatigue', as the war becomes militarily costly and politically unreasonable,” he says.

From the Syrian opposition's standpoint, Russia will remain the more “amenable” and trustworthy interlocutor while the Islamic Republic continues its customary stalling tactics to win the war, and fragment the political arena on both sides of the divide.

As an end game, engaging Russia is not the task of the opposition alone. Gulf and Arab countries are the ones who can ultimately convince Moscow of a less biased position in Syria. This will come at a price: offering diplomatic, military and economic advantages that Russia never enjoyed in the region.

- Mona Alami is a researcher and journalist covering Levant politics. She is a non-resident fellow at the Atlantic Council. Her primary focus is radical organisations. She holds a BA and an MBA in management.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov (R) welcomes his Iranian counterpart Mohammad Javad Zarif (L) before their talks in Moscow on 20 December 2016. (AFP)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].