Arabic to Hebrew: 'The Arab world is full of people, not terrorists'

JERUSALEM - Hundreds gathered to listen to the words of the late Palestinian author Salman Natour on a rainy mid-February evening at the Van Leer Jerusalem Institute. Hebrew and Arabic volleyed back and forth across the crowded auditorium where his verses echoed not only in his native Arabic, but were translated into Hebrew.

"He told us once, ‘you will meet me also after I die, in my books, and in what I wrote.’ So we met him there"

- Inas Natour, daughter of Salman Natour

The audience, packed into seats and overflowing into the aisles, listened with rapt attention in a display of diversity rarely seen in the culturally divided city: young Palestinians sat side-by-side with middle-aged Israeli Jews; a line of older Druze women, clad in loose white veils, anchored the middle of the crowd and spanned an entire row.

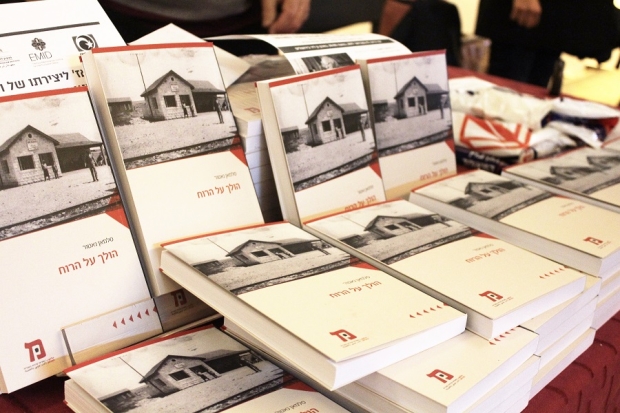

The event organised by Maktoob, a translation and publishing initiative started by Natour and his colleagues at the Van Leer Institute, was both a celebration of Maktoob’s first publication, a trilogy of his works called Walking on Winds, and a memorial. To commemorate his life, it was held exactly one year after Natour suffered a heart attack and passed away on 15 February 2016 at the age of 66.

Changing pre-conceived notions

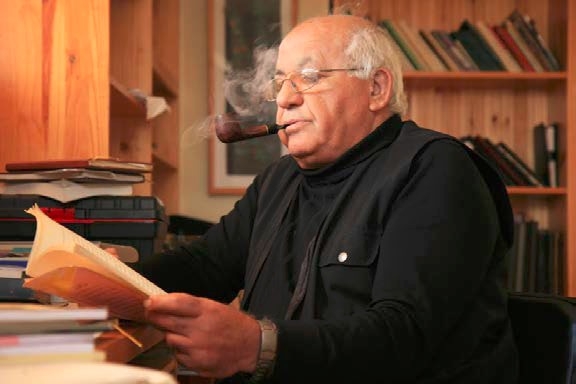

Maktoob focuses on translating Arabic literature into Hebrew, as it is rare in the publishing industry. One of its founding members, Dr Yonatan Mendel, focuses his research on how Arabic is placed among Jews in Israel and Palestine.

'There is a problem, generally, with what Israelis want to know about the Arab world and what Israelis don’t want to know about the Arab world'

- Dr Yonatan Mendel

“There is a problem, generally, with what Israelis want to know about the Arab world and what Israelis don’t want to know about the Arab world,” Mendel explained, noting that many Arab affairs correspondents in Israel tend to be Jewish males with some sort of security or military intelligence background.

“We know that Israelis are really interested in having a Jew going into the Arab world and coming back with information that proves what they already think about the Arab world – that it is full of terrorists, that it is full of fear, full of hatred,” he added.

Maktoob aims to change the negative narrative of Arab affairs which is prevalent throughout Israeli media and academic discourse. Their goal is to bring Arab voices that are free from censored language and military oversight directly to Hebrew readers.

Walking on Winds

Salman Natour is perhaps the best mediator between the two cultures and languages Maktoob is working to unite. He was a writer, playwright, editor and translator whose loss was felt throughout the Arab world.

The Walking on Winds trilogy was not an idea conceived by Natour and was actually put together by the Maktoob team. Three of Natour’s works that speak of homeland and memory were chosen to create a trilogy that explores Palestinian journeys that Hebrew readers have never made.

"Salman is trying to give us a description [through his work] of the Palestinian counterpart in his own words. Not with mediation, and that is the general idea of Maktoob," Mendel said.

In front of the assembled crowd, Mendel read sections of the trilogy in its original Arabic while Natour’s wife Nada deciphered her late husband's prose in the new Hebrew translation. Over coffee shortly after the event, Mendel explained that this was not Maktoob’s original plan.

“We didn’t plan to start Maktoob with a book by Salman, but when he passed away, he left us no other choice,” he said, shaking his head. “We knew that we owed this to him.”

Speaking at the event, Inas Natour, one of Salman’s four children, explained how her father’s outlook was shaped by his Druze identity, having been born in 1949, one year after the State of Israel was founded in what Palestinians call the Nakba - the catastrophe.

'If no one really can read Arabic or read a book or use a letter, there is no way to know the Arab world and the Arab culture'

- Maisalon Dallashi, Van Leer’s translating forum

“My father was tolerant of all the people and all ideas, but he was very idealist,” she said, noting that he identified as Palestinian, Arab and Druze.

“We talked about anything with him and we didn’t think about if he will accept it or [not] – he accepted everything,” she added.

This unique outlook, mixed with a love of wry irony and appreciation of humour, is part of what sets his work apart, according to Mendel.

“Salman had this incredible ability to write about human beings," he said. "He plays with genre, so the journeys are from novels from reportage, to journalism, to novels, to poetic prose."

When his colleagues, family members, friends and fans came together for the launch of Walking on Winds, it was a testament to the cultural boundaries he was able to cross.

A few days after the event, Inas told MEE: “It’s something new from my father, and we felt that we met him there. And on the other hand, he is not there, and we want to tell him about this. It wasn’t easy for us to come home after this, but we were very happy and proud of him."

She added: "He told us once, ‘you will meet me also after I die, in my books, and in what I wrote.’ So we met him there, really."

Bringing the Arab world to Hebrew bookshelves

Maktoob in Arabic literally means “written down”.

“It is written down that this is our destiny," Mendel said. "If we read Arabic literature and we get to know the Arab world, we can also be an alternative to racist voices in Israel. We are trying to communicate to an Israeli audience that the Arab world is not full of terrorists, but is full of people,” he added.

'We are trying to communicate to an Israeli audience that the Arab world is not full of terrorists, but is full of people'

- Dr Yonatan Mendel, co-founder of Maktoob

The Van Leer Jerusalem Institute is something of an incubator of cultural ideas located in the centre of Jerusalem. Supporting projects and research in the humanities, it focuses on the study of Israeli civil society.

For the past three years, it has been home to a forum that brings together Palestinian and Jewish translators and scholars, and Maktoob grew out of this initiative. The publishing objectives are wrapped up right there in the name, which takes on a few different meanings in Arabic.

Finding an audience

Maktoob is not the first publishing initiative to attempt this sort of translation. Yet with grants from the national lottery and the Euro-Mediterranean Institute for Inter-Civilisation Dialogue (EMID), Maktoob is the first of its kind to have institutional support to continue working.

'Less than one percent of Israeli Jews are able to read Arabic literature and the percentage who actually do so approaches zero'

- Command of Arabic among Israeli Jews report

Mifras, a Jerusalem publishing house that was active from 1978 to 1993, managed to publish nine Hebrew translations of Arabic literature. Yet perhaps the best-known translations are those of the Tel Aviv-based publishing house Andalus, which began publishing Arabic works in Hebrew in the year 2000.

Sporting the titles of prominent late poets and writers such as Mahmoud Darwish, Elias Khoury and Hanan al-Shaykh, among others, Andalus published 18 translations before being forced to close after less than a decade. The reason? The books just were not selling.

Maisalon Dallashi, the project-coordinator of Van Leer’s translating forum, helped investigate the root cause of Israeli disengagement with Arabic literature last year, along with Mendel and other colleagues.

The survey, Command of Arabic among Israeli Jews, which was published last summer, found that fewer than 1 percent of Israeli Jews are able to read Arabic literature and the percentage who actually do so approaches zero.

'Arabic is a disgusting language... we don’t feel comfortable to use it in our surroundings'

- comments from Command of Arabic survey of Israeli Jews

“If people answered that they don’t use Arabic, we asked them why,” Dallashi said. “We got answers like, ‘we don’t feel it is necessary because everyone knows Hebrew’ or ‘because Arabic is a disgusting language’, or ‘we don’t like the language’, or ‘we don’t feel comfortable to use it in our surroundings’, but it was basically that they don’t know people they can speak Arabic with.”

Dallashi, a Palestinian from a village in northern Israel, and her colleagues were not necessarily surprised at the results, which they say reflect a familiar day-to-day reality.

"In Israel, if no one really can read Arabic or read a book or use a letter, there is no way to know the Arab world and the Arab culture,” she said.

“I think that Maktoob is the first step to get to know the rich Arab world and Arab culture and history, and politics – not only literature,” Dallashi added.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].