Life after Guantanamo: Former Egyptian prisoner stuck in Bosnia limbo

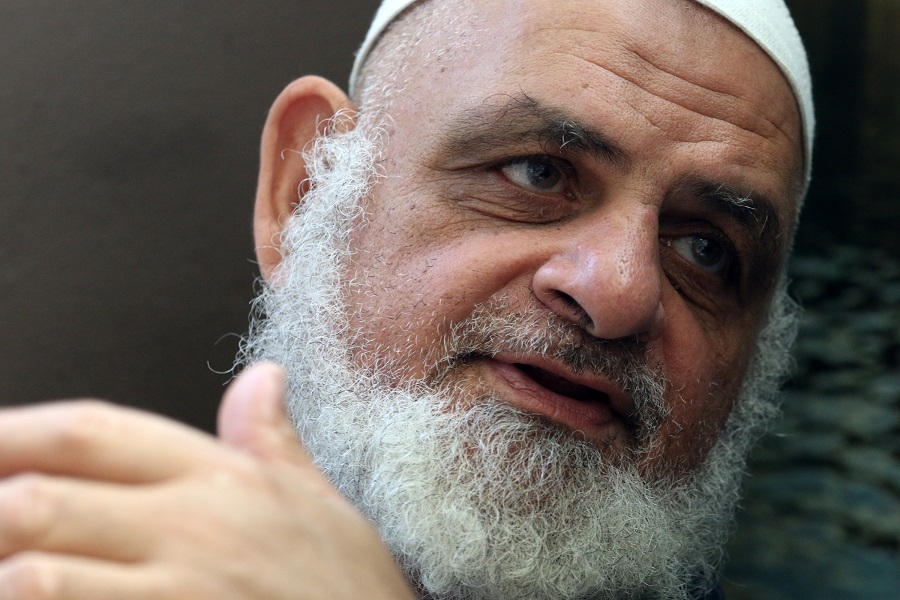

SARAJEVO - Slowly strolling through a housing estate on the outskirts of Sarajevo, Tariq al-Sawah, an Egyptian who was detained at Guantanamo Bay without trial for nearly 14 years, cuts a sombre figure.

“They didn’t even say sorry,” he said. “They just dropped me off at Sarajevo airport after 14 years, and all I had with me was a t-shirt. I live in limbo."

'They didn't even say sorry. They just dropped me off at Sarajevo airport after 14 years, and all I had with me was a t-shirt'

-Tariq al-Sawah, former prisoner at Guantanamo Bay

"Even though Sarajevo is a big city, I don’t have any papers, and I can’t get a job and take care of myself," he added.

Sawah protested at having spent 14 years in Guantanamo without trial, emphasising that, even though his charges were dropped in 2012, he was not released for another four years. He welcomed a legal avenue to challenge his long-term detention, but feels any chances of redress are slim under the new Trump administration.

Even though it has been seven years since former US president Barack Obama signed an executive order to shut down the detention camp in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, and many of its inmates have been released, the prison remains open.

Given US President Donald Trump’s plans to not only keep the camp open but widen its reach, the remaining 60 prisoners, as well as the ones released by the previous administration, fear there is little space for redress. In February 2016, during the presidential election campaign, Trump said that he would "load [Guantanamo Bay] up" with some "bad dudes".

Sawah was released in January 2016 when Bosnia and Herzegovina, a country whose nationality he once held, offered to take him back after charges of conspiring with known members of al-Qaeda and providing material support for terrorism were eventually dismissed against him.

For Sawah, life is a constant economic struggle. He survives by living off donations from local mosques and charities.

After his release from Guantanamo, an agreement made between the Bosnian state and the US government promised him shelter and financial assistance from the Bosnian government. But the living allowance of $125 a month he recently started receiving is too meagre to live on by Bosnian standards.

Sawah also claims that the US government had offered him $200,000 in compensation before his release from Guantanamo, but he said that until now he has not received any money from the US government.

Jelena Sesar, Amnesty International’s (AI) researcher for the Balkans and the EU has reiterated these claims: “We understand that the US government promised financial and legal assistance as a part of Mr al-Sawah’s resettlement, but that assistance never materialised."

However, when asked for clarification, the US State Department did not confirm or deny whether any support package had been put in place.

The Bosnian war

Sawah said that he travelled to the Balkans in the early 1990s as the region was engulfed in a war caused by the break-up of Yugoslavia.

He said he initially worked for the media office at the International Islamic Relief Organisation, known locally as IGASA, in Zagreb, Croatia. From there he moved to Bosnia and worked as a truck driver distributing humanitarian aid before joining the Bosnian army and serving in the 1992-95 war.

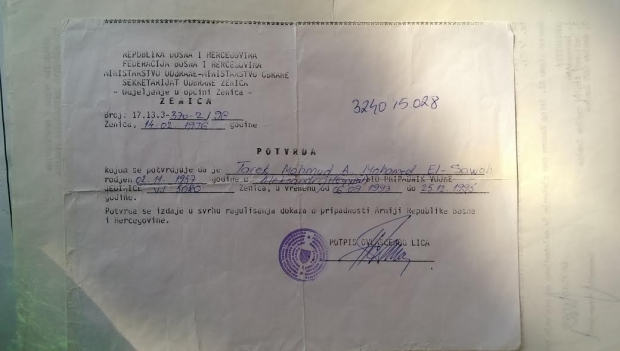

Though Sawah provided no justification or explanation as to why he joined the army, a document issued by the military states that Sawah served in one of its units from September 1993 to December 1995.

Following the 1995 Dayton agreement that ended the war, Sawah said he settled alongside other former foreign fighters and aid workers in the central Bosnian village of Bocinja. Many of the new arrivals, of whom the vast majority were of North African and Middle Eastern origin, married local women and started families.

Sawah married a Bosnian woman and the couple had a daughter who is now a teenager attending high school in Bosnia. Former Guantanamo detainees are often branded as terrorists and assumed guilty and relatives of these individuals often keep a low profile due to fear of scrutiny or attacks.

Reminiscing about how good his life was in Bosnia during the post-war period, Sawah said: “We had land and chickens."

The exact number of former foreign fighters who stayed in Bosnia following the ceasefire is estimated at anywhere from 700 to more than 1,000. Many of them, including Sawah, were given Bosnian citizenship as a reward for their service in the army.

Immigration policy at service of counter-terrorism

Despite their service in the army and their citizenship, the presence of former foreign fighters in the country was later frowned upon by the Bosnian government who said they were endorsing a radical form of Islam. The Bosnian government did not want to be seen as a refuge for Islamic militants and caved in under diplomatic pressure from its international partners to deport the community.

The Dayton agreement stipulated that all forces of foreign origin were to withdraw from Bosnia. Even though many of the men had started families and held Bosnian citizenship, they were still considered a security threat.

Following the 9/11 attacks, the US reportedly intensified pressure on the tiny Balkan country to hand over men it deemed a security threat. The case of the Algerian Six, in which half a dozen men were turned over to US officials and sent to Guantanamo Bay despite being released by a Bosnian court due to lack of evidence, drew international condemnation.

Alarmed by rumours that Bosnia was about to commence deportations, Sawah left for Afghanistan, rather than Egypt, in 2000. He was not the only one who headed for Kabul. Having served in the Bosnian army during the war, many believed going back to their countries of origin carried a risk of prosecution and imprisonment.

Alleged al-Qaeda links

Sawah was reluctant to elaborate on his choice of destination and the nature of the activities he engaged in, but the Detainee Account of Events section of his Joint Task Guantanamo Detainee Assessment provides more details.

It states that the Egyptian travelled “through various al-Qaeda-associated guesthouses before reaching the al-Faruq Training Camp where he received training in urban warfare, mountain tactics, and mortars.

His detainee account states he travelled 'through various al-Qaeda-associated guesthouses before reaching the al-Faruq Training Camp where he received training in urban warfare, mountain tactics, and mortars'

The document also claims that “while the detainee remains a very proliferate source, his account is only partially truthful… Detainee acknowledged he was a member of al-Qaeda and also stated he was not a member.”

It goes on to list Sawah’s alleged bomb-making skills, including the construction of a “shoe-bomb prototype that could be used to bring down a commercial airliner in flight”. It alleges he has extensive terrorist history and personally interacted with a number of high-level al-Qaeda operatives.

During the conversation with Middle East Eye, Sawah stated that he should have been put on trial had the allegations been true.

By Sawah’s account, however, he sustained serious injuries from a cluster bomb while trying to cross over from Afghanistan to Pakistan through the Tora Bora mountains; and claimed he was captured and handed over to the Northern Alliance in 2001.

Following a period in various detention sites across Afghanistan, he was then taken to Guantanamo in May 2002.

Fear of the future

While in Guantanamo, Sawah’s Bosnian citizenship was revoked and thus he is currently living in a state of limbo. Bosnia’s citizen revocation process drew widespread criticism as it allowed no appeal and subjected the individuals concerned to immediate deportation, at times due to minor bureaucratic omissions.

Though Bosnia agreed to take back Sawah in the deal struck with the US government, it is limited to subsidiary protection only, allowing him to stay in the country with limited rights.

Asked whether he still holds Egyptian citizenship or if he receives any support from Egypt, Sawah said he no longer has any links to the country. For now, he is trying to rebuild his life in Bosnia, where his daughter lives.

US responsibility

His dissatisfaction with the lack of substantial support from Bosnia and his desperation at the legal state of uncertainty he is living in are noticeable, but his most bitter complaints are reserved for the US government.

“Amnesty International strongly believes that the US government has the primary responsibility for resolving the problem it has created at Guantanamo,” Sesar said.

She said that the US “must work with host countries to ensure that detainees are successfully resettled after their transfer from Guantanamo, and that their human rights are respected.

"This includes financial assistance to aid successful integration, including for housing, transportation, medical and social support, ensuring access to educational and employment opportunities so that former detainees can learn a trade and/or earn a living wage."

'Amnesty International strongly believes that the US government has the primary responsibility for resolving the problem it has created at Guantanamo'

"This is particularly important for countries such as Bosnia and Herzegovina, which are struggling to address the needs of their own vulnerable populations,” she added.

Despite numerous requests for comment, Bosnia’s Ministry of Security, the body responsible for handling Sawah’s case, refused to respond to any questions regarding his status in the country.

A US State Department official told MEE that they “cannot discuss the specific assurances we receive from foreign governments. However, the decision to transfer a detainee is made only after detailed, specific conversations with the receiving country about the potential threat a detainee may pose after transfer, and the measures the receiving country will take in order to sufficiently mitigate that threat and to ensure humane treatment.”

Sawah's wishes to start a normal life after years of being stuck between today and yesterday, weigh heavily on his mind. For now, long-term plans are not remotely possible, but he yearns for his legal rights to be restored, somehow and someday.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].