‘Maps of Exile’: Europe's ongoing denial over cause of refugees' flight

During a brief visit last year to the Italian city of Naples, I witnessed a sidewalk scene involving three African men selling purses and three conspicuously armed Italian law enforcement officials.

The latter trio was in the midst of guaranteeing public safety by confiscating bundles of purses and taunting the visibly distressed Africans with them, as a crowd of tourists looked on.

Literal invasions are A-OK when done by the right people - but god forbid any resident of previously Euro-pillaged territories attempt to eke out an existence in present-day Fortress Europe

Indeed, across Europe these days, the forcible denial of migrant dignity appears to have been subsumed into the list of on-the-job duties for security personnel.

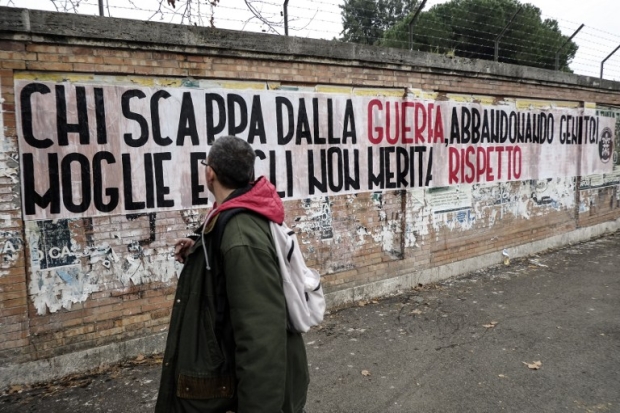

Dehumanising treatment is facilitated by the pejorative rhetoric of Europe’s ruling classes; eternal Italian political fixture Silvio Berlusconi, for example, once complained that parts of Milan were looking too much like Africa. A dutifully xenophobic media furthermore labours to encourage existential fears in the minds of European audiences.

Overlooking history

On my own regular trips to Italy - where my US passport arbitrarily grants me unhindered access and I don’t have to risk my life trying to get there on a rickety boat - I am subjected to countless recaps from Italians of the latest alleged transgressions of migrants in the country.

As the media-fuelled story goes, the invaders from Africa spend their time complicating the lives of the native population in every way possible and generally living like kings at the expense of the Italian government, which joyously flings money at them to spite its own people.

Meanwhile, hyper-territorial Europeans who swear by the sanctity of borders conveniently overlook European history itself in their quest to push the boundaries of self-righteousness.

Shortly after witnessing the police tantrum in Naples involving the three African men, I incidentally happened upon a prominent seaside plaque honouring Italian soldiers who had fallen “in the wars of Africa” while gloriously furthering Italy’s “global mission”.

Apparently, literal invasions and plunder are A-OK when done by the right people - but god forbid any resident of previously Euro-pillaged territories attempt to eke out an existence in present-day Fortress Europe.

The real victims

In his new e-book Maps of Exile, published by Warscapes Magazine, Somali-Canadian journalist Hassan Ghedi Santur observes that - in addition to Europe’s “destructive colonial legacies” - more recent Western military machinations have also contributed significantly to current migration patterns.

Europe’s established complicity in refugee production has not produced any meaningful self-reflection

Beyond the more obvious examples like the Western-backed destruction of Iraq, Santur points out that “many European countries continue to sell billions of Euros worth of weapons to various countries in Africa and the Middle East where violence has compelled thousands to flee”.

For instance, he cites the 2016 revelation that Britain had signed off on $4.1bn of arms exports to Saudi Arabia during the inaugural year of the latter kingdom’s bombardment of Yemen.

Writes Santur: “Saudi Arabia has been using these weapons against Yemeni rebels - all too often killing civilians - even though their British-made cluster bombs are banned by the Convention on Cluster Munitions, an international treaty to which the United Kingdom is party”.

Obviously, Europe’s established complicity in refugee production has not produced any meaningful self-reflection or rendered European terrain any more hospitable for refugees. Instead, the notion persists that the Europeans are somehow the real victims of a refugee crisis that has seen untold numbers of human beings risk their lives to extricate themselves from political and/or economic oppression.

Ordinary people

Rather than working to expose such fallacies, the media all too often shamelessly leaps onto the frontlines of the anti-migrant battle - which is part of the reason that journalism like Santur’s is such a relief.

In Maps of Exile, Santur imparts the stories of people he has met in migrant camps and other locales across Europe, including a young Somali man named Ahmed with whom he spent five days in 2015 in the now-destroyed Calais Jungle in France.

Having fled Mogadishu with his family at age two, Ahmed moved from Ethiopia to Djibouti to Somaliland, where he completed secondary school and where “figuring out a way to [continue his studies] became the next great challenge of his life”.

He eventually earned a bachelor’s degree in Sudan and applied for scholarships to continue his education in Europe. Rejected, he embarked on a perilous odyssey that took him from Egypt across the Mediterranean Sea to Italy, Germany, and finally France.

Near the end of Maps of Exile, Santur reflects on his final meeting with Ahmed:

“As I listen to Ahmed talk about his hopes and dreams, I am struck by just how ordinary they are. There is no denying that the current migration crisis unfolding in Europe is extraordinary. But take away the extraordinary numbers of refugees and migrants marching across the continent - take away the daring acts of desperation, strip away the hyper-polarised politics - and what’s left are ordinary people with the most ordinary yearnings: safety, freedom, jobs.”

If only humane journalism were more ordinary.

- Belen Fernandez is the author of The Imperial Messenger: Thomas Friedman at Work, published by Verso. She is a contributing editor at Jacobin magazine.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: Refugee families from camps around Athens take part in demonstration in March 2017 by Greek anti-fascist groups against European Union's stance on refugees (AFP)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].